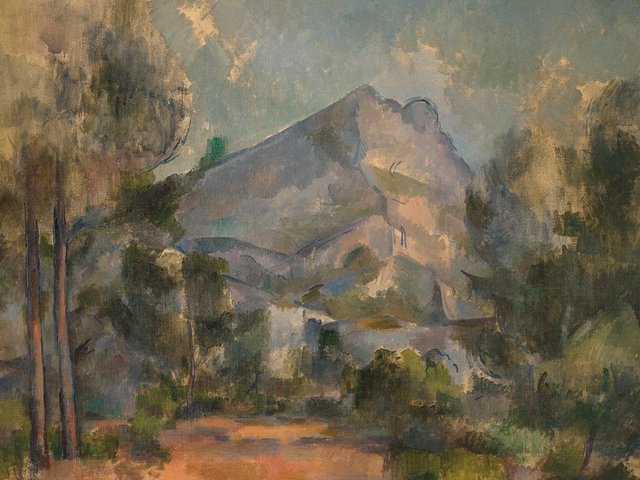

Paul Cézanne’s painting La Montagne Sainte-Victoire (1897), which was formerly contested between the Kunstmuseum Bern and the artist’s descendants, quietly went on show in France for the first time in May. It is the result of an innovative agreement to share an art object with competing claims to its ownership. As the art world continues to ponder the delicate and painful questions of restitution, I believe this settlement offers a roadmap for resolving similar legal disputes in the future.

La Montagne Sainte-Victoire emerged in 2012 in the collection of the late Cornelius Gurlitt, an elderly recluse who owned around 1,500 works of art, some of which were looted by the Nazis. He had inherited them from his father, Hildebrand, a dealer who bought art in occupied France for Hitler’s planned Führermuseum in Linz, Austria. Cornelius Gurlitt bequeathed the trove to the Kunstmuseum Bern in Switzerland in 2014.

Provenance research published in the Cézanne catalogue raisonné and the German Lost Art Foundation’s Gurlitt Provenance Research Project shows that Cézanne’s family owned the work until at least 1940. But there are no further records of the painting’s whereabouts until a 1947 letter by Hildebrand Gurlitt. This gap in provenance made it impossible to confirm how Hildebrand came to acquire it and whether the Nazis had looted the work.

The sharing agreement reached by the Kunstmuseum Bern and Cézanne’s heirs in July 2018 is thanks to the pioneering negotiations of several people: the head of the museum’s decision-making board, Marcel Bruelhart; the museum’s director, Nina Zimmer; its lawyer, Katharina Garbers-von Boehm; Philippe Cézanne, who represented the artist’s family; his lawyer, Jutta von Falkenhausen, and Walter Feilchenfeldt, co-author of the artist’s catalogue raisonné, as trusted art historical expert.

The painting is currently on view at the Musée Granet in Aix-en-Provence, Cézanne's hometown. From left: the Kunstmuseum Bern's director Nina Zimmer, Philippe Cézanne, lawyer Jutta von Falkenhausen and members of the Cézanne family

Normally, similar cases would not be able to proceed beyond the gap in provenance. Here, both parties agreed to move past this unresolved issue, yet leave it open for review if new documents emerged for the period in question. Since the painting’s original owners were neither Jewish nor political opponents of the Nazi regime, both sides concluded that it would not be considered Nazi-looted art even though Hildebrand Gurlitt owned it at one point. Acknowledging what could not be known and leaving the provenance question open marks a step forward in legal thinking.

The Cézanne agreement also recognises the different meanings of “art property” for public institutions and private owners. Whereas individuals can sell their property at will, in some countries the law prohibits museums from de-accessioning or selling objects in their collections; in Switzerland this is not illegal but discouraged. De-accessioning a work carries the risk of it disappearing into a private collection where the public would not have access to it. In the case of La Montagne Sainte-Victoire, both sides agreed that this outcome would not be desirable. They concurred that the Kunstmuseum Bern would own the painting while Cézanne’s heirs would have the right to exhibit it elsewhere.

The family, too, privileged a public solution, choosing to celebrate the artist’s origin by lending the work to the Musée Granet in Cézanne’s hometown of Aix-en-Provence for three months each year. This arrangement has advantages for everyone: the painting can now be shown in two museums and enjoyed by audiences in France as well as in Switzerland. Both sides express pride in the fact that no money changed hands as part of the agreement and much of the legal work was carried out pro bono.

In my opinion, the settlement is legally, diplomatically and art-historically wise; rather than seeking a binary yes/no answer, it follows a more nuanced art historical practice of accepting that more knowledge can emerge about a work of art in the future. The negotiators made it their common goal to privilege public access to culture. Finally, the sharing arrangement honours the work’s original provenance.

This model contains the ingredients of what I call a “matrimonial” rather than a “patrimonial” approach to cultural property: avoiding conflict in favour of co-operation, privileging co-existing needs and values over rival interests and understanding the mutual benefits of sharing.

- Sharon Hecker is an art historian who specialises in modern and contemporary Italian art. Her forthcoming book is titled From Cultural Patrimony to Cultural Matrimony: a New Way of Dealing with Disputed Art Objects (2020). This article is based on a chapter of the book.

- The exhibition Sainte(s)-Victoire(s), featuring Cézanne’s La Montagne Sainte-Victoire, continues at the Musée Granet in Aix-en-Provence until 29 September.