Just outside of Saugerties, New York, is Opus 40, a six-acre structure built from thousands of bluestones arranged by hand into terraces, walkways, vistas, and ramps. The massive interactive sculpture is the life’s work of the artist Harvey Fite, who toiled on it for 37 years before his death in 1976. The unfinished piece is a testament to the wondrous and crazy things humans can create—and it is now in a period of transition.

After years of being overseen by Fite’s stepson, Tad Richards, the Opus 40 Sculpture Park & Museum appointed Caroline Crumpacker as the new executive director last autumn. She aims to make the site more financially sustainable, deepen its ties with the community, and expand the programmes offered to the public. “I have a lot of experience, creating partnerships in the arts in various ways—with other non-profits, with artists, with different communities,” says Crumpacker, who was previously the director of the Millay Colony for the Arts in Columbia County. “This is one of the things that I want to start at Opus 40—which isn't to say that has never happened before—but to really expand the ways that we engage the community.”

Crumpacker sees this happening both by offering more educational trips to Opus 40 for students in the area, from the elementary to college level, as well as offering a larger variety of concerts at the site, and she is in early talks with the nearby station Radio Woodstock to plan programming. She is also looking into the possibility of purchasing Fite’s residence on the site, which Richards still lives in, and turning it into part of the park.

“We’re trying to bring more theater to the space, poetry readings, and other groups to really make it a premier performance venue for art in the Hudson Valley,” says Jonathan Becker, the chairman of the Opus 40 board of directors and a vice president at nearby Bard College. He adds that the transition is happening at the encouragement of Richards, to preserve Fite’s achievements with a more professionalised operation.

A dance performance at Opus 40

Opus 40’s financial situation has been mostly stable, “but it has depended on the kindness of the Richards family to maintain it,” Becker says. “There are two issues: first, things do go wrong, like when a hurricane hit and damaged walls; and second, the Richards are incredibly loyal but are not getting younger. We are hiring a full-time staff and need to make sure that the financial model allows Opus 40 to thrive beyond their support and to withstand the unexpected.”

“In terms of a legacy, everyone who sees it comes away thinking about it differently,” says Richards. “Some people say, ‘Oh my god, this was a life changing experience’, while others come away thinking, ‘Why did I come here to see a pile of rocks.’” Sitting in a floral-printed armchair, his small dog Sidney perched in his lap, and the monolith of Opus 40 visible through the window behind him, Richards remembers one thing Fite said often about his work: “The man who carves bluestone must create a design of lasting dignity, or his work will live to mock him.”

One man’s magnus opus

Fite was born in Pittsburgh on Christmas Day 1903, but grew up in Houston, Texas. As a young man, he seemed to live a life always in motion, exploring whatever opportunities might come to him, whether that be law school, square dancing, or running away from studying the ministry in the Hudson Valley to join a theater troupe. After a theatre performance one evening, a seamstress’s wooden spool rolled under his chair and he began whittling it with the pocketknife he often carried with him. This was the beginning of what would become his long career as a sculptor.

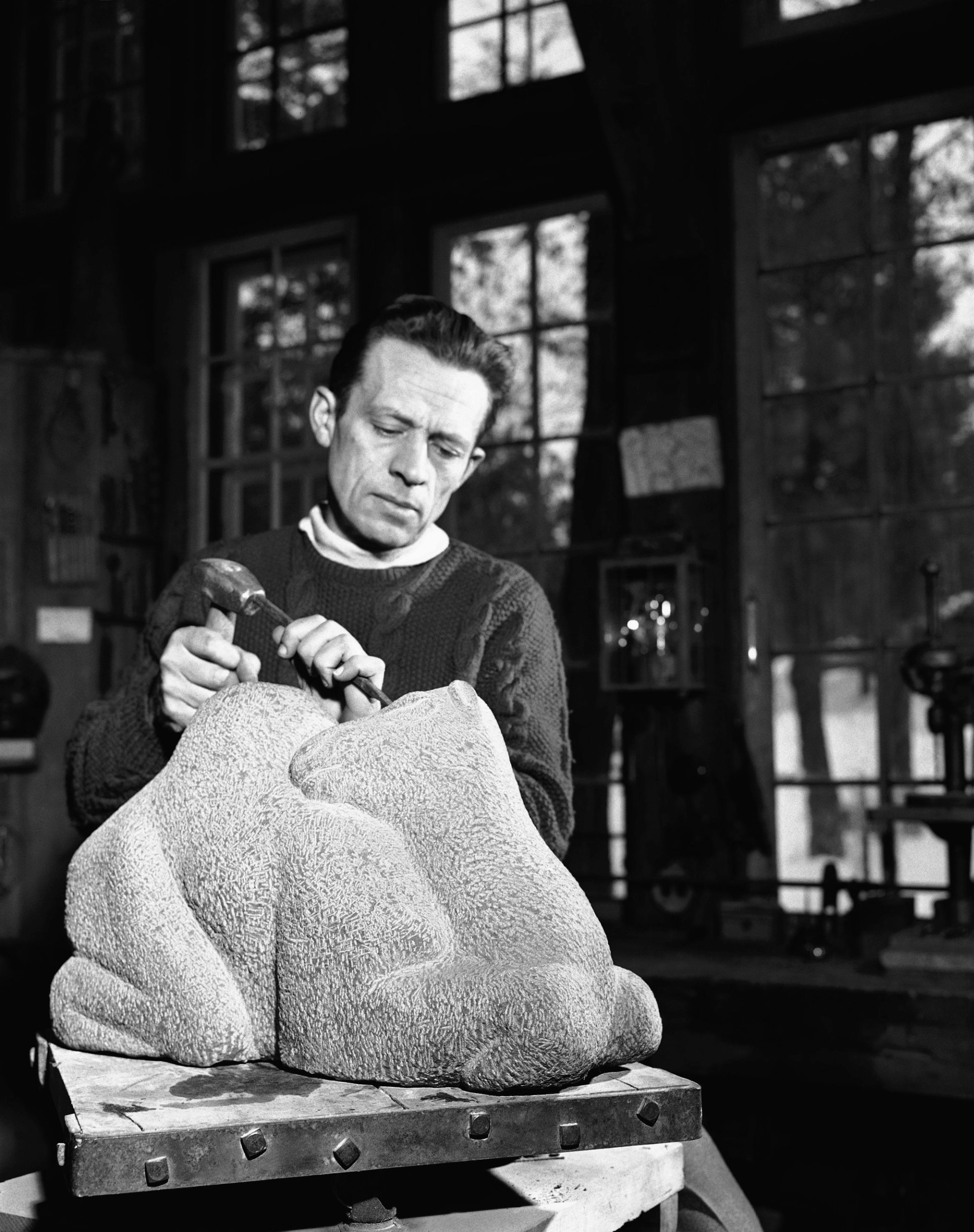

Harvey Fite working on a figure of a sleeping camel inside his quarry studio in upstate New York, 26 February 1948 AP Photo/RAW

He took up sculpting full-time at the age of 30 and five years later, wandering the woods in nearby Saugerties, New York, he came across an abandoned bluestone quarry, which he bought in 1938 for a total of $250, according to Richards.

Originally, Fite saw the quarry as a place to source raw stone for his sculptures, but he also thought it would make a great sculpture garden if he carved alcoves and pedestals out of the quarry to house the pieces he made. He soon came to see the quarry itself as a massive piece of art. The summer he bought the quarry, he went to Honduras to help restore Mayan sculptures and he came back with an appreciation for the stone laying techniques used there, which he would apply to Opus 40, Richards says.

Fite set about hand placing stones at the site, weaving them together like a jigsaw puzzle that rose into an undulating, built landscape. Every feature of the site orbits around the highest point of Opus 40, a pedestal that houses a nine-ton bluestone pillar that cuts against the backdrop of the sky and surrounding mountains like a baroque Washington Monument.