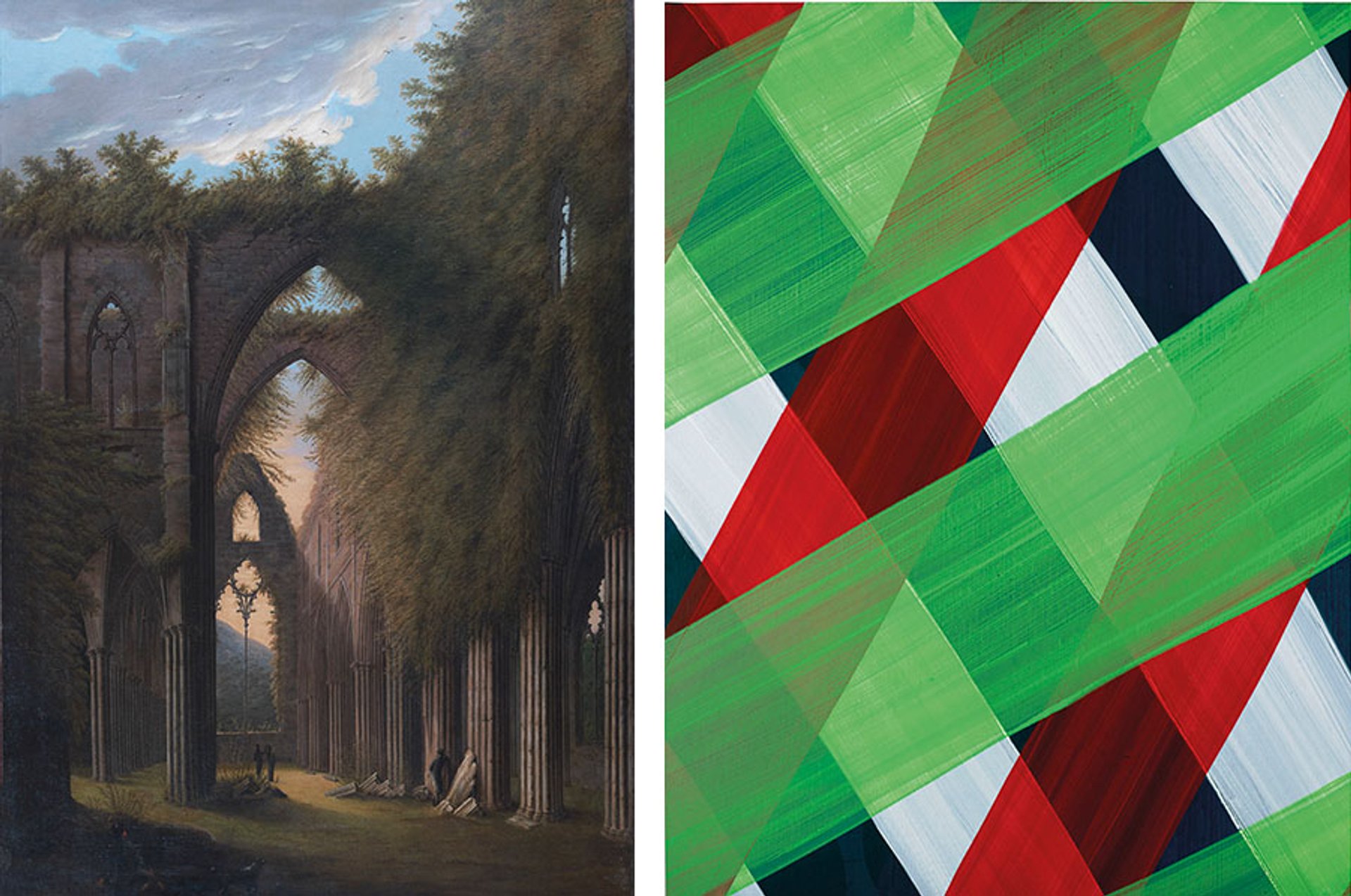

“Out With The New” (and, by implication, In With The Old) suggested Christie’s promotional blurb for its latest Classic Week of sales in London.

The old art that Christie’s and other auction houses and dealers offered this July certainly looked a whole lot cheaper than the sort of prices currently being paid for contemporary pieces. But does the old necessarily represent better value? The vast majority of today’s collectors favour contemporary, and the pendulum of collecting fashion doesn’t look as though it’s going to swing back through the centuries any time soon.

Here is a selection of latest prices in the Old Master field, compared to what you could get for similar amounts at the previous week’s contemporary auctions. Only time will tell us where value and the smart money is.

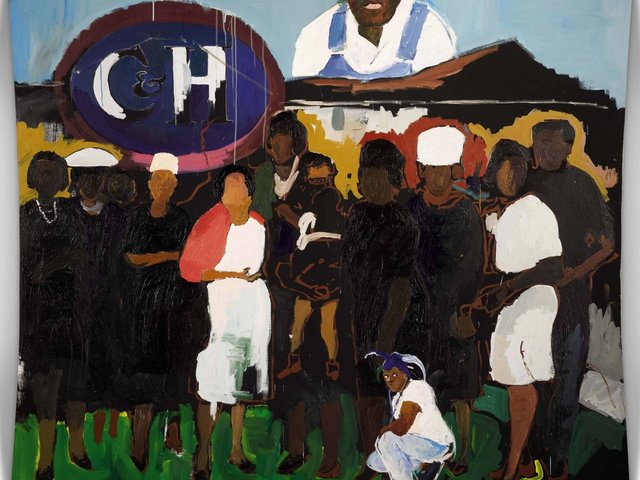

Old London Bridge by the Dutch artist Claude de Jongh (top) sold for £1.1m with fees last night while David Hockney's 1991 canvas, What About the Caves, sold for £1.3m last week De Jongh: courtesy of Christie's. Hockney: courtesy of Sotheby's

The international collector base for European Old Masters looked worryingly thin on Thursday at Christie’s evening sale of Old Master paintings. Against a pre-sale estimate of £13.8m-£20.7m, the auction raised just £12.2m (£14.9m with fees) from 50 lots, with a third of the material unsold. Only three works managed to exceed a million, among them the top lot, Bernardo Bellotto's view of Venice, the Molo, with the Doge’s Palace, the Piazzetta and the Libreria, looking west which sold for £2.3m (£2.7m with fees) and an atmospheric signed and dated 1650 oil on panel painting of Old London Bridge by the Dutch artist Claude de Jongh.

One of just two smaller variants left in private hands of the artist’s celebrated version of this subject at Kenwood House, north London, it was fresh to the market from a descendant of Francis George Baring, 2nd Earl of Northbrook. All this inspired at least four bidders to push the painting to £900,000 (£1.1m) with fees, double the mid-estimate and a record for the artist.

Cutting edge contemporary artists don’t really go in for De Jongh-style topographical painting any more, but David Hockney’s surreal 1991 canvas, What About the Caves, is a landscape of sorts, albeit a bit bigger. It sold, almost unnoticed, for a low estimate £1.3m (with fees) at Sotheby’s evening sale of contemporary art last week that took £58.4m (£69.6m with fees).

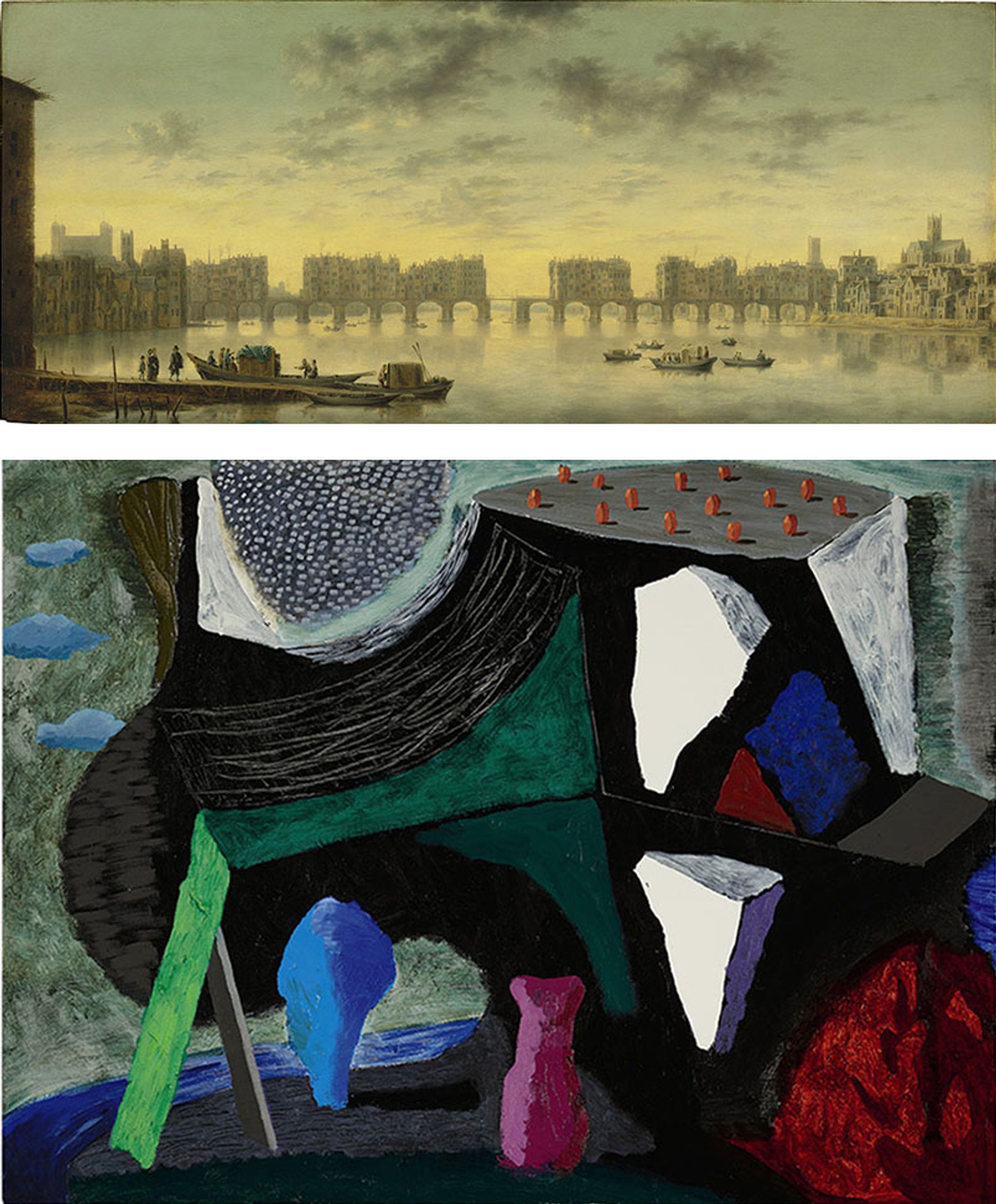

A 19th-century depiction of Tintern Abbey priced in the region of €45,000 and Untitled (2005) by Katharina Grosse, sold last week for £56,250 Tintern: courtesy of Paolo Antonacci. Grosse: courtesy of christie's

One of the most intriguing old pictures sold in the last few days was a large canvas of the famous ruins at Tintern Abbey, Monmouthshire, offered by the Rome dealer Paolo Antonacci during London Art Week. Acquired from a private collection in Rome, this unsigned painting looks suspiciously like the work of an early 19th-century German artist, but Antonacci is not sure whether it is by a British or continental hand. With an asking price of €45,000, it was sold to a German collector. “It was a sleeper,” Antonacci says. “It was impossible to value.”

That may be so. Yet the relatively modest asking price for this old painting made a telling comparison with the £56,250 (with fees) paid last week at Christie’s contemporary day sale for the slightly smaller geometric abstract, Untitled (2005), by Katharina Grosse. The on-trend German artist is best known for her monumental site-specific painting, but this work was one of her more generic canvases of an apartment-friendly size that can routinely be seen at contemporary art fairs.

In terms of sheer rarity and quality, The Lost Tapestries of Charles I at the St. James’s textiles specialists S. Franses was surely one of the stand-out shows of London Art Week (27 June-5 July). The dealers presented a newly discovered hand-woven tapestry of Dido and Aeneas, that is the sole survivor of a lost series of Voyages of Aeneas hangings made by Charles’s Mortlake factory in the 1640s, based on cartoons by the leading Italian Mannerist artist, Perino del Vaga. It is priced at around £1m.

Coincidentally, Gerhard Richter’s 2009 abstract canvas, Musa, sold for £1m with fees at Christie’s evening contemporary sale on 25 June, setting an auction record for this artist in the medium. Unlike the Mortlake tapestry, this Richter hanging was machine-woven and was one of an edition of ten.

A hand-woven tapestry of Dido and Aeneas from the 1640s priced around £1m and a Gerhard Richter's 2009 machine-woven abstract canvas, Musa (from an edition of ten) sold for £1m last week Dido and Aeneas: courtesy of S. Franses. Richter: courtesy of Christie's

Thanks to two major campaigns of iconoclasm, English pre-Reformation art is also pretty rare, which is why it took Sam Fogg three decades to put together his Medieval Art in England exhibition (until 26 July). Among the 66 pieces on show is a late-15th-century alabaster relief of the head of St. John the Baptist, unusually retaining much of its original paint. It was sold for £50,000 with fees, an “entry” level for a serious collector of contemporary art. Exactly the same price was given for the large bronze sculpture Cave (Panel), from 2010, by Thomas Houseago at Christie’s 26 June contemporary sale. Again, this was an editioned piece, one of five numbered sculptures, plus two artist’s proofs.

Time and again this week we have seen high quality, unique objects from previous centuries selling for the same price as editioned pieces from this century. Sotheby’s 2 July sale of ancient art, for instance, included a rare figure of a goddess from the enigmatic Etruscan civilisation, datable to the 2nd century AD. Equally rare for an Etruscan antiquity at auction was its documented provenance stretching back to the 18th century. This sold slightly over estimate for £75,000 with fees.

The previous week, on 28 June at a Phillips contemporary day sale, a similar-sized bronze figure, titled FINAL DAYS, by the former street artist Brian Donnelly, aka KAWS, sold for £106,250 with fees. Dedicated followers of the art world will know that the auction market is currently in the grip of Kawsmania. But still, this was quite a price for a sculpture of a cross-eyed Smurf, given that it had been made in 2017 and was from an edition of 25.

Out with the new? Perhaps not quite for now.