The photographer Cindy Sherman grew up in New York’s Long Island in the 1950s. She was a self-confessed “child TV addict”. Her parents would leave her at home to go to parties, and she would watch the same films on repeat. Her favourite childhood film, Alfred Hitchcock’s Rear Window, is “her blueprint,” the curator Paul Moorhouse says ahead of Sherman’s first retrospective in the UK, at London’s National Portrait Gallery. “That’s how I understand her work,” Moorhouse adds.

Sherman would repeatedly watch the wheelchair-bound Jimmy Stewart as he in turn obsessively observes his neighbours, attempting to fathom their lives via fragmentary visual glimpses. In adulthood, Sherman would quote Grace Kelly’s instruction to Stewart: “Tell me everything you saw—and what you think it means.”

“Sherman’s art poses the very same challenge,” Moorhouse says. “She invites us to see her and then work out what she means. She is pure appearance.”

Her favourite childhood film, Rear Window, is "her blueprint"

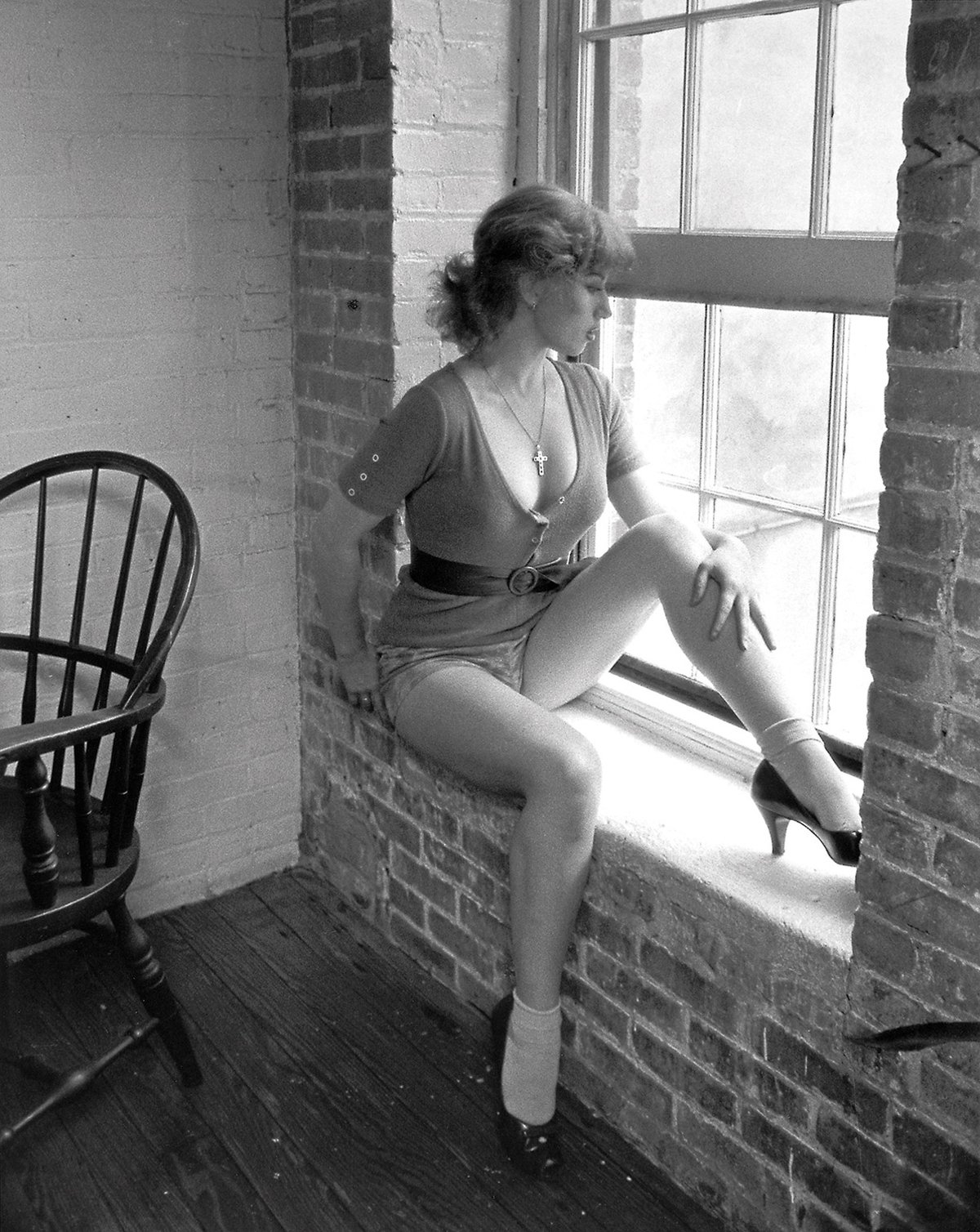

Between 1977 and 1980, Sherman photographed herself repeatedly for a series she called Untitled Film Stills. Mostly confined to her apartment in New York, Sherman transformed herself into a litany of different personas or alter egos: the characters of fictional films. She presented herself as a matinee starlet, a flapper, a femme fatale, an all-American girl, a dormouse librarian or a lonely suburban wife.

In a 2003 essay on making Untitled Film Stills, Sherman wrote: “I loved all those vignettes Jimmy Stewart watches in the windows around him. You don’t know much about any of those characters, so you try to fill in the pieces of their lives.”

When it was released in the early 1980s, Untitled Film Stills was met with a combination of confusion and indifference. She sold a few prints from the series for $50 apiece, and struggled to be exhibited in established galleries in New York. (In March, Untitled Film Still #21 sold for more than $800,000 at Sotheby’s London).

Cindy Sherman's Untitled Film Still #17 (1978) Courtesy of the artist and Metro Pictures, New York

Moorhouse, a former curator of 20th-century art at the National Portrait Gallery, worked closely with Sherman and numerous collectors to make the series whole again before bringing it to the UK for the first time. The series, which Moorhouse calls “performances captured as portraits”, will comprise a major part of the overall retrospective.

Untitled Film Stills was revolutionary; today, Sherman’s influence is difficult to avoid. From fashion shoots to war photography, it is common to overhear discussions around performance and perception, or to note reference to ‘set-up’ photography, in which narrative-based scenarios are minutely constructed and plotted before being captured on camera.

Sherman succeeded in “expanding the definition” of portraiture by actively “presenting a false image”, Moorhouse says. And that makes her “almost uniquely current”.

“There’s a sacrosanct notion, a holy cow, in art history: that we can read a person’s character by looking at their face,” Moorhouse says. “We’re always looking at other people and trying to work out who they are. But the truth is we can never really tell. You can only interrogate their appearance.”

Cindy Sherman's Untitled #574 (2016) Courtesy of the artist and Metro Pictures, New York

Understanding and exploring that tension lies at the heart of Sherman’s art, Moorhouse says. And this tension is ever more pressing when seen through the prism of social media and projected identity.

“No other artist interrogates the illusions presented by modern culture in such a penetrating way,” Moorhouse says. “Advertising, fake news, social media, even pornography—no other artist scrutinises so tellingly the façades that people adopt or our struggle to make sense of what’s presented to us via our cultural outposts.”

Also on show at the museum is The Cindy Book. “It’s not actually a work of art. It’s a very personal, very private memoir,” Moorhouse says. The book is a family album Sherman started when she was eight and completed in college. She collected pictures of herself, her family, her friends and first boyfriends through her childhood and teenage years.. “It’s the earliest evidence I can find of Cindy’s fascination with her own changing appearance,” Moorhouse says.

Underneath each image of herself Sherman wrote the words “That’s Me”. The statement also acts as a question, Moorhouse says. “And it’s an obsessive question: ‘That’s me? Is that really me?’ It sets the tone for her life’s work. And I believe her work will only become more important.”

The show is sponsored by Wells Fargo.

• Cindy Sherman, National Portrait Gallery, London, 27 June-15 September