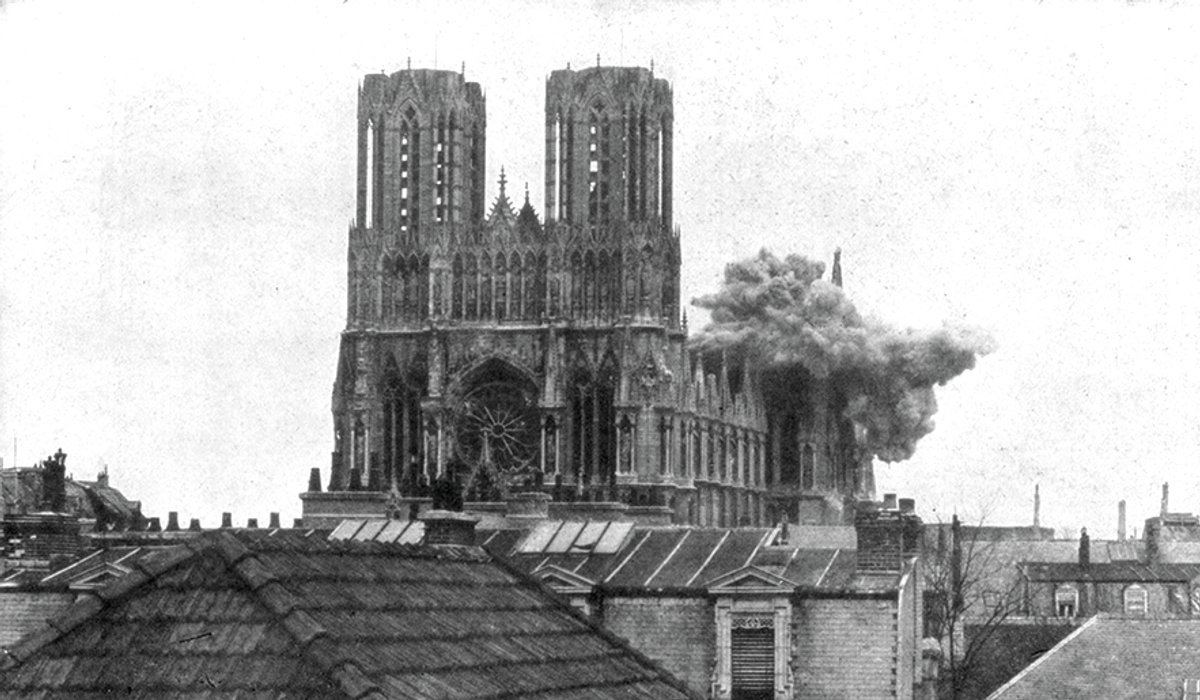

The shelling of Rheims Cathedral in the First World War was a split-second military decision – but one that would have huge consequences. The burning cathedral became a symbol of the cultural war between Germany and France.

Thomas Gaehtgens’s book’s subtitle, War and Reconciliation between France and Germany, hints at an educational intent. For his English-language readership, he has provided a lengthy introduction that outlines the significance of this “profound intellectual rift between the two nations” and notes: “Widely circulated in visual media of the day, the picture of the burning cathedral became deeply imprinted in European memory.”

The military sequence of events is quickly told. In the autumn of 1914 the German army dug in just outside Rheims, while the French needed to hold the city at all costs in order to protect Paris. On 19 September 1914 the cathedral started burning. The fire was spread by extensive wooden scaffolding on two sides of the building, erected before the war for restoration work. Gaehtgens cautiously reaches the conclusion that the German bombardment of the towers—mistaken for an observation post—happened by accident rather than design. Over the four years of the war Rheims was almost completely destroyed.

Gaehtgens takes the intellectuals of both countries to task. He speaks – and this is effectively the core theme of his book—of the failure of the intellectuals: “Instead of denouncing the senselessness of the war—with only a few exceptions, such as Romain Rolland in France and Albert Einstein in Germany—they surrendered themselves to nationalistic hubris and blind deference to authority”. French propaganda was countered by an open letter An die Kulturwelt! (to the cultural world), printed in many German newspapers and signed by 93 academics, artists and writers, ranging from Max Planck to Max Liebermann. French accusations were roundly dismissed on military and tactical grounds: “We utterly refuse to purchase the rescue of a work of art with a German defeat”. Yet intellectual defeat could no longer be averted: “After the shelling of Rheims, it no longer seemed conceivable to maintain scientific, cultural and personal contacts” and worse, says Gaehtgens, “the intellectuals of both countries missed the opportunity to raise critical voices against further calamities”.

After this, the ruined cathedral became synonymous with German “vandalism”, a concept disseminated in countless, invariably doctored postcards. All of this is impressively presented with superb illustrations.

Gaehtgens’s book is something of a conclusion to the many centenary publications about the First World War’s destruction of cultural heritage. He closes his book—really a history of changing attitudes—with a chapter on the role played by Rheims in the reconciliation between France and Germany after the Second World War. Readers, then, having encountered outpourings of rage and hatred in the wartime propaganda, can witness with amazement and gratitude how natural and self-evident this reconciliation has become.

- Bernhard Schulz is the art critic of Der Tagesspiegel, Berlin

- Thomas W. Gaehtgens, translated by David B. Dollenmayer, Reims on Fire: War and Reconciliation between France and Germany, Getty Publications, 296pp, £45, $55 (hb)

- C.H. Beck, Die brennende Kathedrale. Eine Geschichte aus dem ersten Weltkrieg, 351pp, €29.95 (hb)