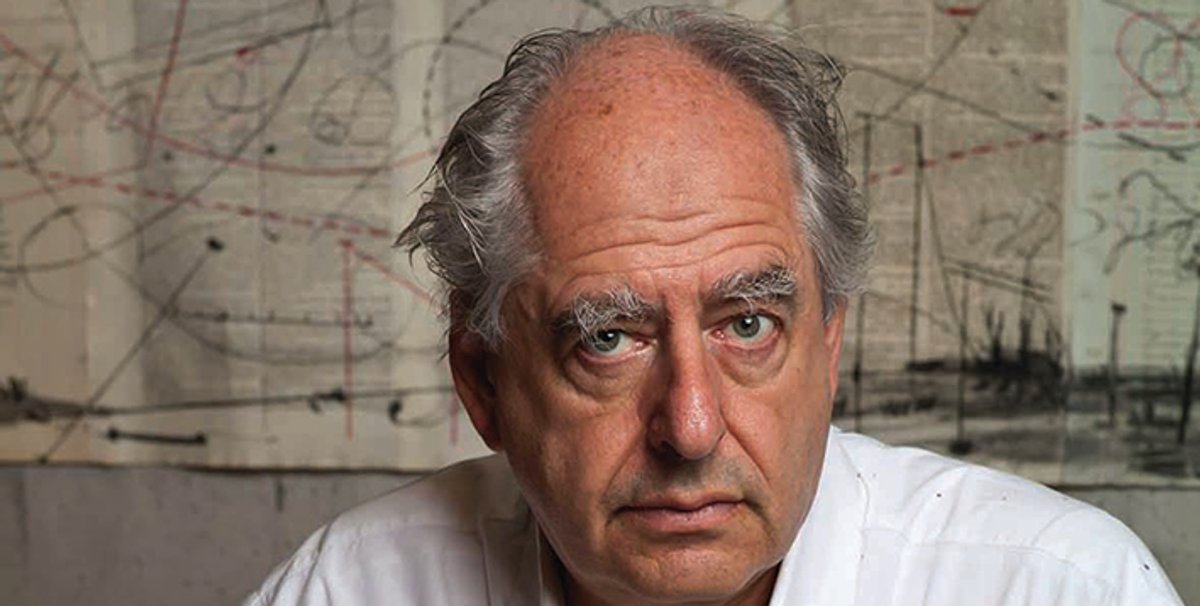

It Speaks to Me, a new book by The Art Newspaper’s Jori Finkel, features 50 artists from Marina Abramovic to Gillian Wearing on works that inspire them from museums around the world. It is published this month. Here, we feature an excerpt, in which the South African artist William Kentridge discusses Antoine Bourdelle’s Large Sappho (1887, cast 1925), a bronze sculpture in the Johannesburg Art Gallery.

When I was growing up, this sculpture gave me a sense of the power that art could have, both in terms of scale and my immediate attraction to it. I didn’t know it was supposed to be the poet Sappho then—I thought of it as “A Woman with a Harp.” Actually, I thought of it as “My Woman with a Big Toe.”

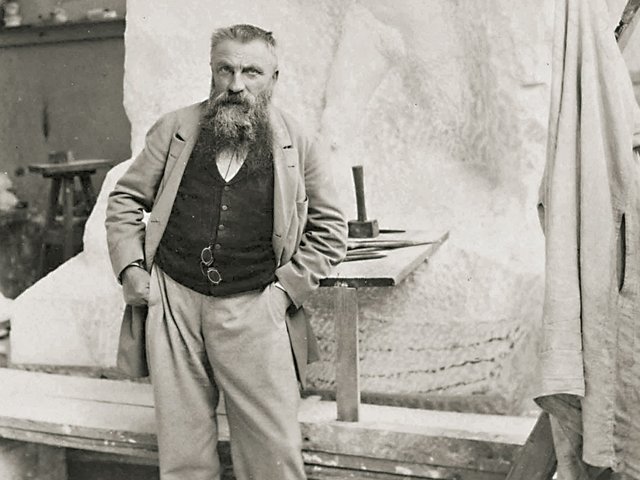

Antoine Bourdelle, Large Sappho (1887, cast 1925) Courtesy of the Johannesburg Art Gallery

It’s a large bronze sculpture, larger than life, of a woman with her elbow resting on the soundboard of a harp. What held me, the compelling detail that Roland Barthes described as the punctum of a photograph, is the toe: her right foot is flexed and the big toe is pointed upward. There’s something about the tension of this toe, embodying a kind of extraordinary power.

The size of the sculpture meant that her knee and head and breasts were all out of reach, especially for a child. But the toe was so close. There was, I think, something erotic in that toe, even for a six-year-old, but quite what—I would have to speak to my analyst to find that out.

The sculpture sits somewhere between the sculpture of Rodin—Bourdelle was one of his assistants—and early Cubism. You can see Rodin in the modelling and half-twist of the figure. She’s not quite a Thinker, as she hasn’t swung all the way to place one elbow on a knee, which looks correct in the sculpture but is actually extremely uncomfortable. But her torso is turned. Also, she is an immensely strong and muscular woman, and the hands and forearms are fantastic in their power. This is not a delicate, Renaissance-thin wrist. It’s a wrist that comes out of Rodin or even Michelangelo. If you take away the dress, it could certainly be a man’s arms and wrists.

Then there are echoes of Cubism in the angularity of the lyre and its simplification of shape and form. Bourdelle is flattening the curved surfaces of the instrument, breaking down the world into a series of facets.

The sculpture I’ve been doing recently has something of these angularities. I wouldn’t put too much emphasis on it, but there is some common language. I’m certain that one’s head is filled and formed by these early encounters with particular works of art.

• It Speaks to Me: Art That Inspires Artists by Jori Finkel, DelMonico/Prestel, 168pp, £19.99/$29.95 (hb)