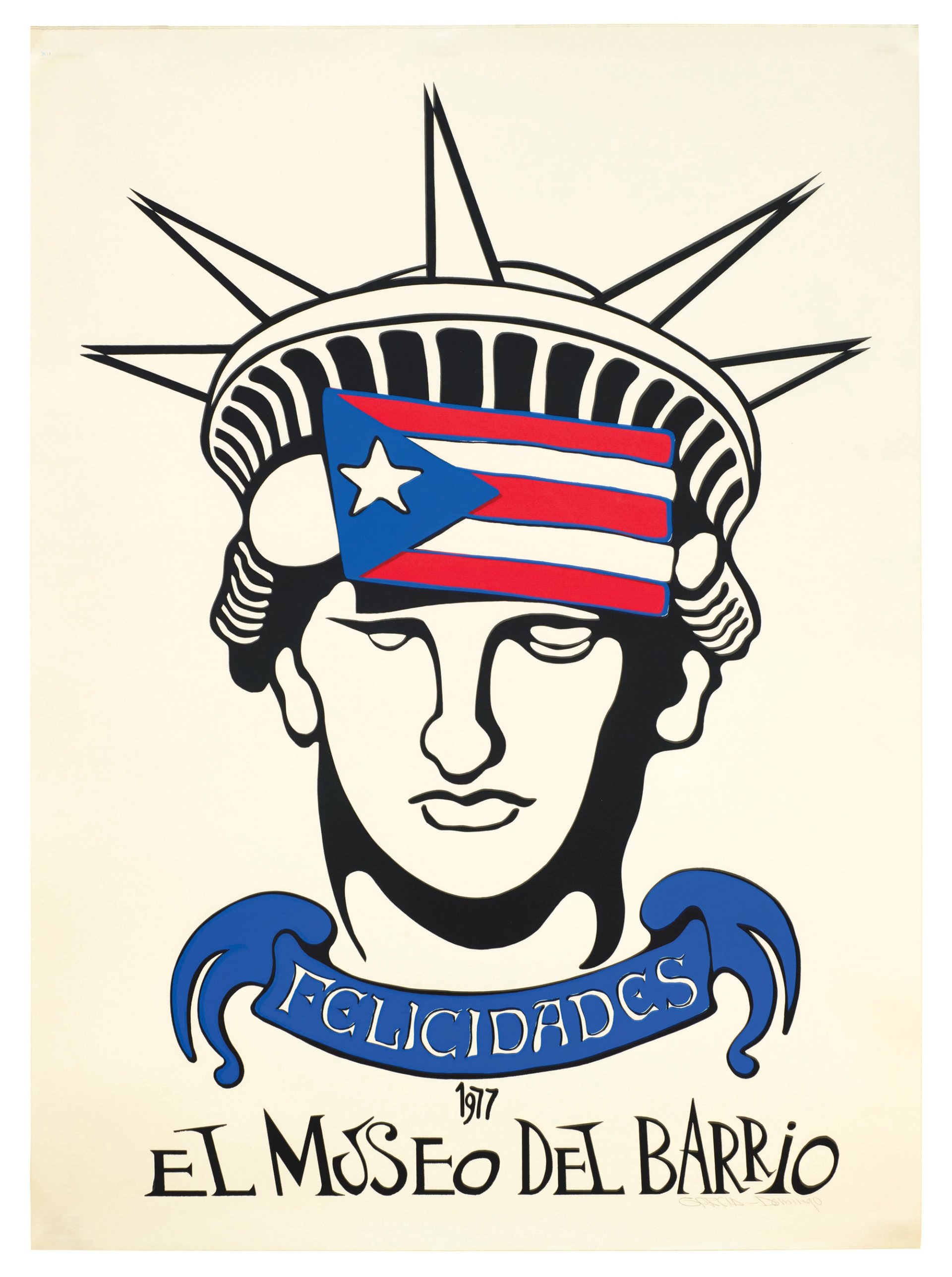

Lady Liberty and the flag of Puerto Rico Illustration: Domingo Garcia

One of the first things you see when you enter the exhibition Culture and the People: El Museo del Barrio, 1969-2019 (until 29 September), the museum’s 50th anniversary show, is a grouping of five photographs by Hiram Maristany. The artist, who is perhaps best known for his role as the official photographer for the Puerto Rican political activist group the Young Lords, was involved with El Museo del Barrio in its early years, serving as director for a time in the mid-to-late 1970s. His photographs capture scenes from the New York museum’s early existence. In two of them, children stand before modest signs announcing the institution’s presence with grins on their faces.

Maristany’s heartwarming photographs are a clear reminder of El Museo del Barrio’s roots: it began as an educational project that emerged from the decentralisation of New York City’s schools in 1969. Puerto Rican parents in East Harlem—also known as Spanish Harlem or El Barrio—wanted their children to learn about their own history and culture. Working with their district superintendent, they hired the artist Raphael Montañez Ortiz to develop a curriculum. Instead, Ortiz had the idea to create a museum that would be by and for the community.

In the ensuing decades, El Museo has grown from a grassroots project to an international institution. It has expanded its mission to represent not just Puerto Rican culture, but that of “all Latin Americans in the US”. It has found a permanent home and presented critically lauded exhibitions—but has also faced financial troubles, high staff turnover and waves of protest from local residents. Maristany’s photographs are an evocative symbol of the museum’s origins but they also amplify a question that has continually come up for debate: what is El Museo del Barrio’s future, and how should it reflect the past?

Significant backlash

The museum began its 50th year with controversy. In January, following significant backlash, it scrapped a plan to honour a right-wing German princess at its gala. A few weeks later, it cancelled an exhibition devoted to the filmmaker Alejandro Jodorowsky, after his claims to having raped a co-star resurfaced.

The anxiety is that El Museo del Barrio has been lost, taken from our handsJuan Sánchez, artist

In March, activists published a document, Mirror Manifesto, which has since been signed by more than 500 people. It warns against the museum becoming “an elitist institution for Latin American art” and calls on it to embrace the many Latinx communities in the US by becoming (in spirit, if not in name) El Museo de los Barrios (“museum of the neighbourhoods”).

“The anxiety is that El Museo del Barrio has been lost, taken from our hands,” says Juan Sánchez, an influential Nuyorican (New Yorker of Puerto Rican decent) artist who signed the manifesto and whose mixed-media painting Bleeding Reality: Así estamos (1988) is on view in Culture and the People. Sánchez has a long history with El Museo that stretches from visiting as an undergraduate art student in the 1970s to having a solo show there in 1999 to participating in protest campaigns.

Barrio Boogie Movement (2006), by Rodríguez Calero Courtesy of Rodríguez Calero

Sánchez explains that the current tension stems from the perception that the museum is privileging Latin Americans abroad over Latinx artists in the US, as seemingly demonstrated by the recent recruitment of a director, Patrick Charpenel, from Mexico, and a chief curator, Rodrigo Moura, from Brazil. “El Museo del Barrio has always been embracing of Latin America, but to convert the museum to just a Latin American museum would mean to elbow Puerto Rico out and for that to become second, maybe third priority,” Sánchez says. “The anxiety is that it will gradually erase the history, the founding, and the purpose of the museum.” Such fear is exacerbated by the fact that the market and scholarly institutions have taken up Latin American art as a valuable category while continuing to sideline Latinx art.

For other artists, too, El Museo was deeply important in its early decades. Perla de León showed her work there for the first time, in a 1979 exhibition of nine Latina photographers titled Mujeres 9, curated by Evelyn Collazo. “I think back and realise, this woman did the first exhibition I know of with all-female photographers, and then we were all Latina photographers, which was amazing,” De León says. “What I loved about the museum when it first started was that it really did have a lot of activist people involved and a desire to exhibit work in the community or by the community.” Five works from a series she was making at that time, South Bronx Spirit, are in the current show.

Act of protest

One work missing from the exhibition, however, is a self-portrait by Marta Moreno Vega, who served as El Museo del Barrio’s second director and went on to found the Caribbean Cultural Center African Diaspora Institute. In March, before the show opened, Vega withdrew it in an act of protest. “The base of creating the museum was to make sure our community saw themselves reflected on the walls… and my feeling is that is not happening,” she says. “How can our own institutions exclude us?”

The Metropolitan Museum of Art have increasingly begun to pay attention to groups they had previously ignored, including Latinx people and African Americans

Vega sees what has happened at El Museo del Barrio within the larger context of New York City’s competitive art ecosystem. “I think the institution is trying to figure out, how do you survive in this framework?” which Vega identifies as “overwhelmingly” Eurocentric, white and male. Meanwhile, she notes that, in recent years, institutions such as New York’s Brooklyn Museum and the Metropolitan Museum of Art have increasingly begun to pay attention to groups they had previously ignored, including Latinx people and African Americans. “They understand the population shift, and El Museo does not,” Vega says.

If the present-day problems of El Museo del Barrio seem numerous, so too do the potential solutions. Mirror Manifesto has six demands, including the creation of a residency programme for emerging Latinx artists, a commission to lead the decolonisation of the institution and greater diversity among the staff and board. Deborah Quiñones, a longtime El Museo del Barrio activist who has organised much of the current charge, says she had been meeting with the institution for months about staffing issues but was not informed that Moura had been hired as chief curator. “That was frustrating, because I told everyone I would be willing to work with them,” she says, “but if you mess up, I don’t have a problem going in on you, because I have unfinished business.”

The Flag (2003-06), by Nicolás Dumit Estévez Courtesy of Nicolás Dumit Estévez

That business is another protest campaign she led in 2002—but the energy was different then, Quiñones says, when more people turned up for action. A community meeting last month drew about 20 people. After introductions, discussion settled on the board of trustees, which Jorge Daniel Veneciano, who directed the institution from 2014 to 2016, says is fundamental to understanding its inherent tensions.

“The practical problem is in the museum’s board-finance structure, which is no different from that of any other museum in the city,” Veneciano says. “The difference for El Museo lies in the particular social class tension between the values of Museo, expressed by the board, and Barrio, expressed by the community. One seeks international prestige, the other seeks local pride.”

Community concern

Charpenel says he recognises the need for more community members and Nuyorican representatives on El Museo’s board. “I think we have to work hard to have a diversified board that is really engaged with the institution,” he says, “that supports not only with economic resources.” Despite the controversies, Charpenel thinks his and the museum’s priorities align with those of the community. “I really believe there is a lack of representation for Latino communities and Latin Americans in the US,” he says. “I truly believe that the mission and the concerns of El Museo del Barrio are precisely community concerns.”

Since the publication of Mirror Manifesto, the museum has taken some steps towards rapprochement, including a new post for a curator of Latinx art, one of the activists’ demands. But it remains to be seen if the men who are now helming the institution can do what a slew of directors and curators in the past decade have not been able to: reconnect El Museo with its Barrio roots.

• El Museo del Barrio’s Patrick Charpenel and Susanna V. Temkin have curated Diálogos, a special themed section at Frieze New York focusing on works by Latinx and Latin American artists