Where does New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), a radical institution when it was founded in 1929, fit among the city’s plethora of contemporary art venues—and the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s increasing focus on diverse international contemporary art—90 years on?

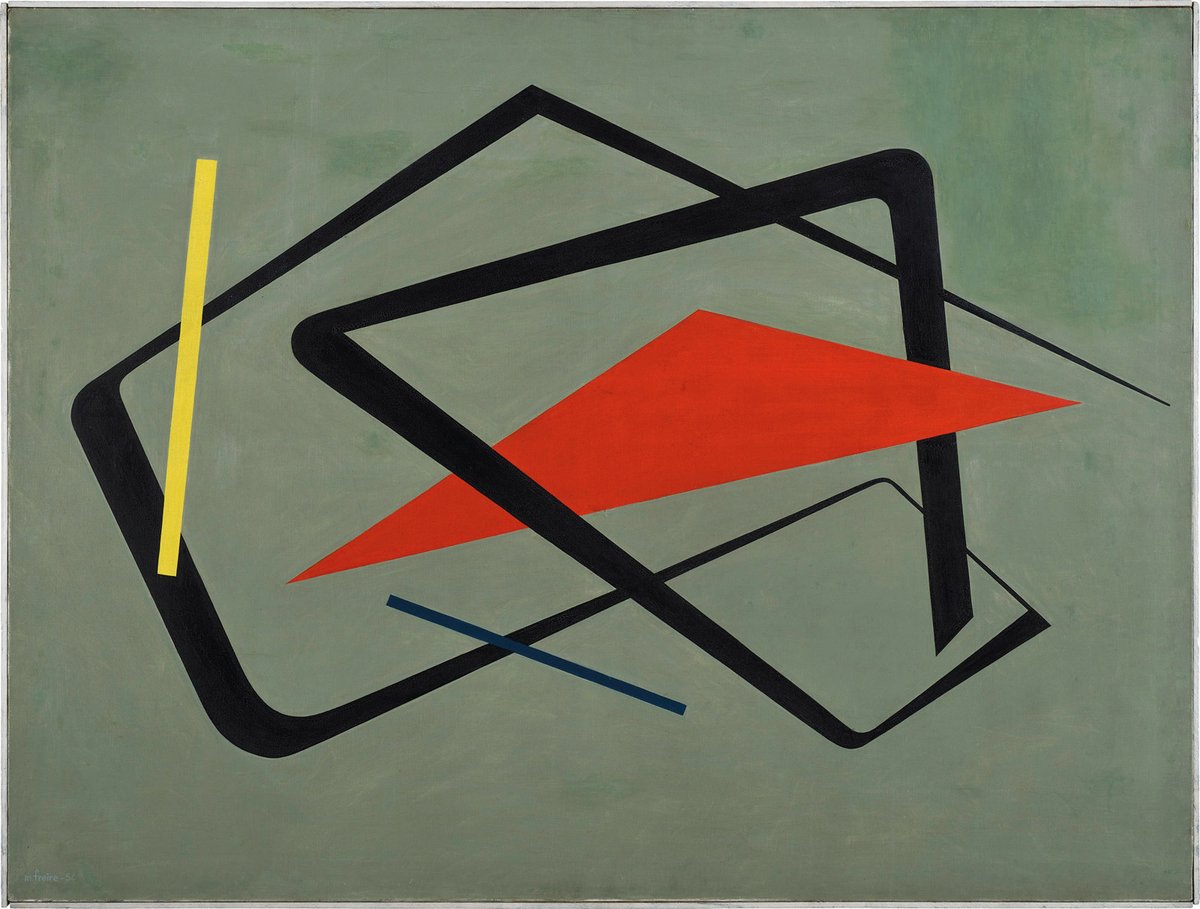

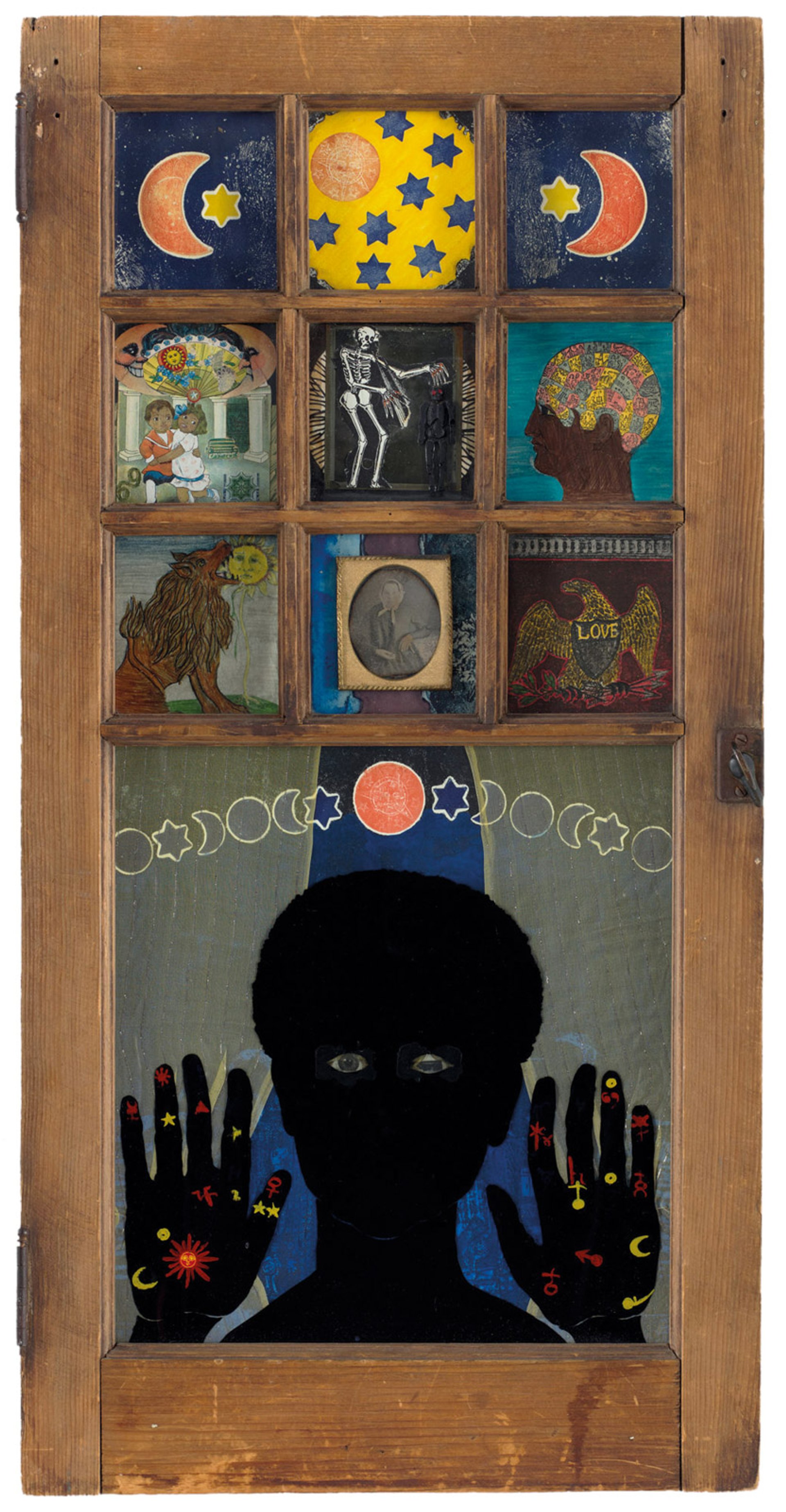

“What makes us very different is our collection,” says Christophe Cherix, MoMA’s chief curator of drawings and prints. The 200,000-strong permanent collection will be put front and centre for the planned October reopening of the museum following a $400m revamp that adds around 30,000 sq. ft of space to display the collection. All the opening exhibitions will draw on MoMA’s holdings, including recent acquisitions and gifts, in shows such as Sur moderno: Journeys of Abstraction (21 October-March 2020) on Modern Latin American art, and Betye Saar: the Legends of Black Girl’s Window (21 October-January 2020).

“What we want to do is recapture the initial sensibility of the museum, which was one of being challenging and provocative,” says Ann Temkin, the chief curator of painting and sculpture. Almost a century on, there is a perception that MoMA has become “much more of an authoritative, institutional body, rather than that vibrant, thinking place”.

The museum is doing away with linear, evolutionary chronology in its new permanent collection displays, which will rotate every six to nine months. Instead, they will mainly be anchored by a “chronological spine” that allows for the mixing of different mediums and works from around the world from the same period—and with the flexibility even to include works from other periods in a chronological room “as a provocation or an echo or a complement”, Temkin says.

“I think the overall goal [of the rehang] is to point out the plenitude of art over the past 150 years, and the richness of all the many directions,” she adds. “Now it’s a ‘pluriverse’, not a universe. MoMA is not here to say this is better and this is worse, or this is right and this is wrong—which I’m not sure we ever did as much as we’ve been caricatured as doing—but instead just say, here is what we think is fascinating and outstanding.”

Betye Saar’s Black Girl’s Window (1969) Courtesy of MoMA

The curators have also been seeking to fill gaps in the collection. Last May, for instance, MoMA acquired 324 early 20th-century works on paper from the Merrill Berman collection, which “changed the way we tell the story of the avant-garde”, Cherix says. “We thought we had everything of the avant-garde, but guess what? We had very few works by women artists; we didn’t have anything regarding photomontage, which might be the language of the 20th century.” The acquisition also added more central and eastern European artists from the period.

The museum wants New Yorkers and tourists alike to come back to see the permanent collection, not just special exhibitions. MoMA plans to give rehangs the rituals that go along with loan shows, like opening events and members’ days, Temkin says.

“The ratio of staff and budget and time that in former years was allotted to collection display has been very small vis-à-vis what’s been allotted to temporary exhibitions,” Temkin says, adding that the consistent rethinking of the collection will change this. “The museum was always a mix of those two things, but somehow... all the ad money, all the framing money, all the—you name it—slowly drifted toward the loan shows.” It is a trend she attributes to “the late 20th-century explosion of the blockbuster and attendance focus”, which “maybe wasn’t even a conscious shift”.

She continues: “Our real legacy is what we buy. If we’re all buying crummy stuff right now, MoMA is going to be in big trouble in 50 years. MoMA will not be what MoMA is today, if we’re acquiring unimportant work. Whereas, if we’re doing unimportant shows these few years, MoMA will survive. It’s a monumental rethink of the infrastructure of the museum, in that way.”