Seventeenth-century Dutch still-life paintings

Dutch Golden Age pictures executed with “simplicity and cleanliness” are what buyers want, says Toby Campbell of the Old Master specialists Rafael Valls in London. He identifies ‘modern’ Old Masters—those that sit comfortably in a contemporary white-walled space—as driving this demand: “The more lavish floral still lifes—unless they are very early—tend to be less popular now.”

Among those making big sums are the small and unfussy still lifes of Adriaen Coorte: in 2014 a buyer paid £3.4m (with fees) for one at Sotheby’s London. Another sought after name is Clara Peeters, a Flemish painter who made her career as part of the Dutch Golden Age. ”Her works have a very crisp finish and that appeals to modern tastes,” says Campbell. One of the few women active as a professional painter in early modern northern Europe, Peeters was given her own show at the Prado in Madrid in 2016-17 (the museum’s first ever exhibition devoted to a female artist). The market-wide interest in female artists has also helped elevate the prices for Peeters: a crystalline flower and insect still life sold for £634,000 (with fees) at Sotheby’s in London last year.

There is a dwindling supply of exceptional examples in the genre— a much bemoaned affliction of the whole Old Master market. Therefore, when top examples by the major names do come up, they regularly command seven-figure sums, Campbell says. The David Koetser Gallery caused a stir at Maastricht last year when it unveiled an exceptional still life by Ambrosius Bosschaert the Elder, found in a private collection. This year, the Richard Green Gallery will be showing Still life with a pewter jug, a 1630s oil by Pieter Claesz priced at £1.3m.

Galerie Kevorklan is showing a Luristan votive cudgle (€20,000-€30,000) © Thierry Olliver

Near Eastern Antiquities

Covering the entire pre-Islamic Middle East, the diverse field of Near Eastern antiquities includes “the great empires of antiquity such as the Hittites, The Babylonians, the Assyrians, the Achaemenid Persians, the Phoenicians, the Parthians and the Sassanians”, says Madeleine Perridge, the director of Kallos Gallery in London. Particularly prized, Perridge says, are items “related to the great kings of this period, such as Nebuchadnezzar, Ashurbanipal, Cyrus, Xerxes, Darius and the Sassanian kings of pre-Islamic Iran”.

Controversies over ancient artefacts from the Near East have been much documented, thanks to the Gulf War conflicts of the late 20th century and the more recent Islamic State destruction and looting of heritage sites in Iraq and Syria. Therefore, Perridge says, the importance of provenance “cannot be overstated”. She adds: “Objects originating from Syria and Iraq are both subject to various international restrictions. For example, The Iraq (United Nations Sanctions) Order 2003 prohibits the importation or exportation of any cultural property illegally removed from Iraq since 6 August 1990.”

Ancient art from Mesopotamia—the historical region nestled within the Tigris-Euphrates river system in western Asia—has been a hot topic recently. Last autumn, an Assyrian gypsum relief, unearthed from the royal palace at Nimrud, sold for $31m at Christie’s, New York—the second highest price at auction for a piece of ancient art. It was followed by the major I am Ashurbanipal: King of Assyria, King of the World exhibition at the British Museum, which closed last month, and, most recently, coverage of the controversial export of the Assyrian reliefs from Newbattle Abbey College (see cover story, The Art Newspaper, February 2019).

As Mesopotamian art features some of the earliest known texts, inscriptions are a popular collecting area, says Perridge: “Excellent quality cuneiform tablets with particularly interesting subject matters are certainly desirable to collectors as they are not only beautiful to look at but can also present such a wealth of historical information in miniature form.” Abstract idols—such as the eye idols of Tell Brak—are also in vogue among collectors of Modern and contemporary art.

At Tefaf, the Paris-based Galerie Kevorkian will exhibit a group of pieces, mostly produced in the Ancient Iranian world between the 3rd millennium BC Bronze Age and the Parthian dynasty in the first centuries of the Christian era, with a majority of Luristan bronzes coming from a French collection established in the 1970s and built over several decades.

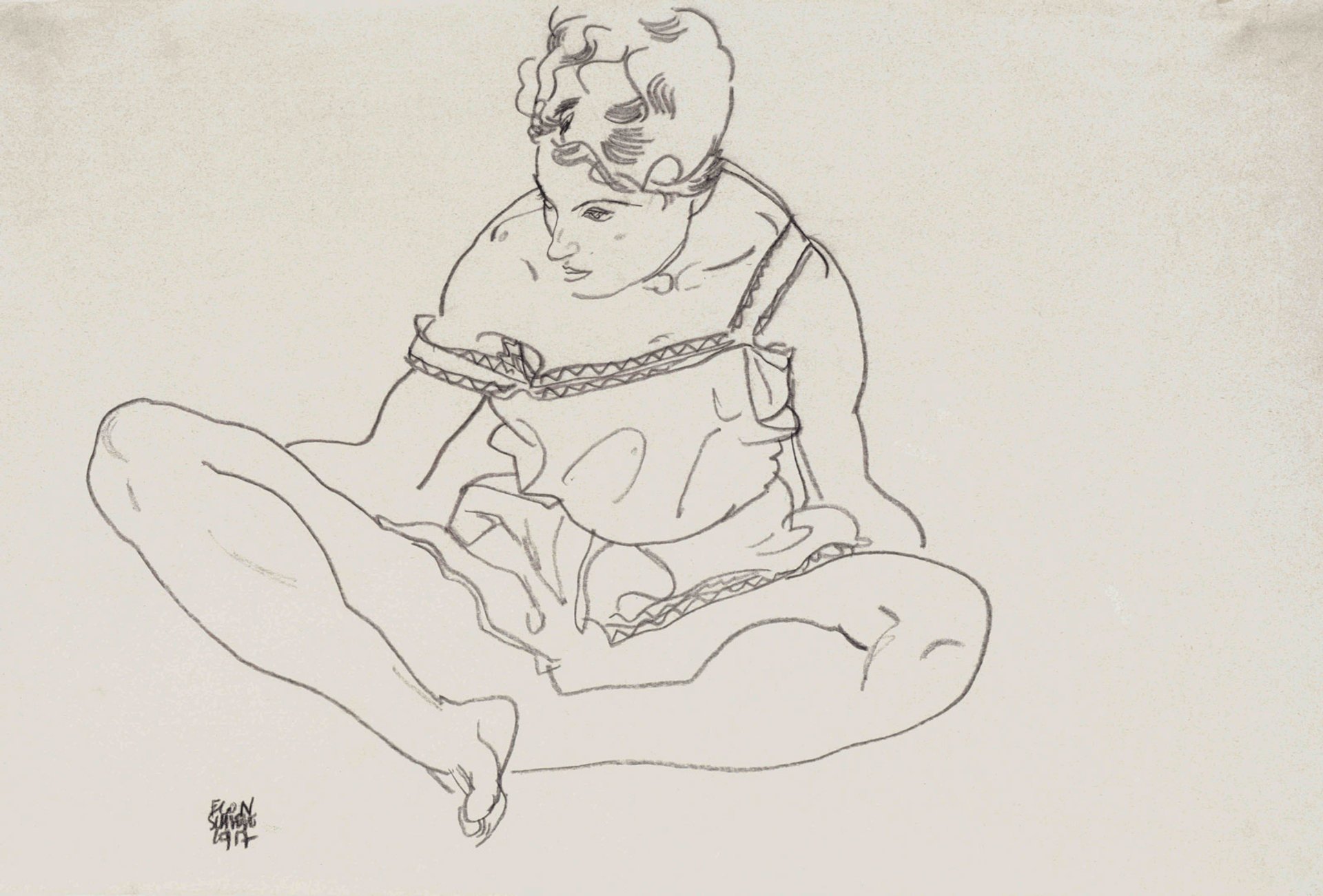

Adele (Seated Woman with Crossed Legs, 1917), a crayon on paper by Egon Schiele, is on sale for €480,000 at Richard Nagy. ©Private Collection; Courtesy Richard Nagy Ltd.

Expressionist works on paper

The amorphous term Expressionism is most closely associated with German artists such as Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Emil Nolde and Paul Klee, although other early 20th-century European artists, including Oskar Kokoschka, have also been linked with the movement. But the output of the core Expressionists was relatively small, and is hard fought over today by collectors spread across the US, Europe and Asia.

Prints, a medium seized upon by many of the Expressionists, are a flourishing area, says the London-based dealer Richard Nagy. Those of the Norwegian Edvard Munch are in especially high demand and soon to be the focus of a show at the British Museum—Edvard Munch: Love and Angst from 11 April to 21 July. When it comes to buying and valuing works on paper, condition is paramount, says Manuel Ludorff of Galerie Ludorff in Düsseldorf: “The market for Expressionist works on paper certainly demands immaculate condition and colour.”

Ludorff points to Emil Nolde’s watercolours: “Clients really appreciate the saturated depth of the colours that Nolde used in his watercolours, of which unfortunately the majority have faded over the past 70 to 90 years.” At Tefaf, the gallery will show two Nolde watercolours priced at over €200,000 each—they, Ludorff says, are in “near perfect” condition.

Perhaps the best known (and most divisive figure) of the movement in Austria was Egon Schiele, whose centenary was celebrated last year with around half-a-dozen exhibitions around Europe, including Klimt/Schiele: Drawings from the Albertina Museum, Vienna, which recently ended at London’s Royal Academy of Arts. “This is confrontational art, so it does not appeal to a mass audience,” Nagy says. “It requires a certain amount of knowledge, so the collectors in this area tend to be established and more aware of the marketplace: they don’t rely on advisers and auctioneers to tell them what is good and what isn’t.”

According to Artnet’s price database, the auction record for a work on paper by Schiele stands at £7.9m (with fees) for Liebespaar (Selbstdarstellung Mit Wally) (Lovers (Self-portrait With Wally), 1914-15), a watercolour sold at Sotheby’s London in 2013.

Nagy’s stand at Tefaf Maastricht will include Adele (Seated Woman with Crossed Legs) (1917), a crayon on paper executed by Schiele in 1917 and priced at €480,000.

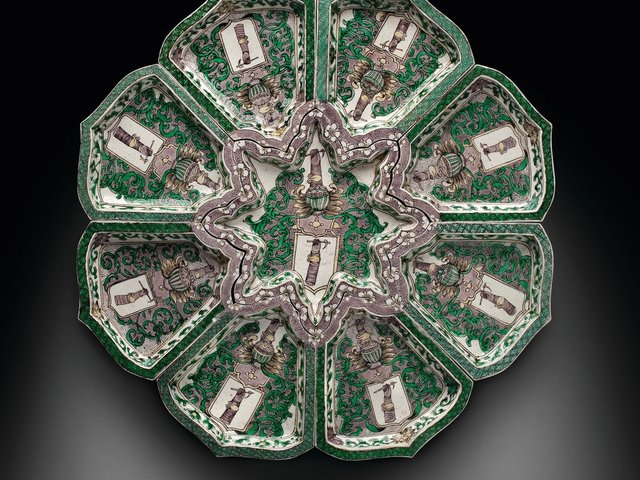

A Chinese porcelain Pronk charger from the Qianlong period is priced at €95,000 (Vanderven Oriental Art) Vanderven Oriental Art

Asian Export ware

The market for Asian export ware has remained largely unchanged since the late 16th century when the first pieces of ceramics and decorative arts were dispatched from China to the West. The specialist dealer Floris van der Ven says around 90% of collectors still come from Europe and the Americas, as well as the Middle East. The “very international scope” of collectors, he says, means “you find clients in a large part of the world.”

Pieces made during the reign of the Chinese Emperor Kangxi (1662-1722) are especially desirable. “There was intense trade with Europe, which was blossoming in a relative peaceful moment, and production and quality were high during this period,” Van der Ven says.

Unlike the market for non-export Chinese pieces, fakes are less of a concern as the price level in general is much lower and export pieces tend to have been circulating in the western world since they were ordered new. But beware of later copies, says Ronald Fuchs, the curator of the Reeves Collection at Washington and Lee University and a vetter at Tefaf Maastricht: “One of the challenges with Chinese export is that it was made in such vast quantities, and designs have been made for long periods of time, honestly copied, and dishonestly faked.” A large Chinese porcelain Pronk charger, commissioned by the Dutch East India Company during the Qianlong period, is priced at €95,000 at Vanderven Oriental Art.

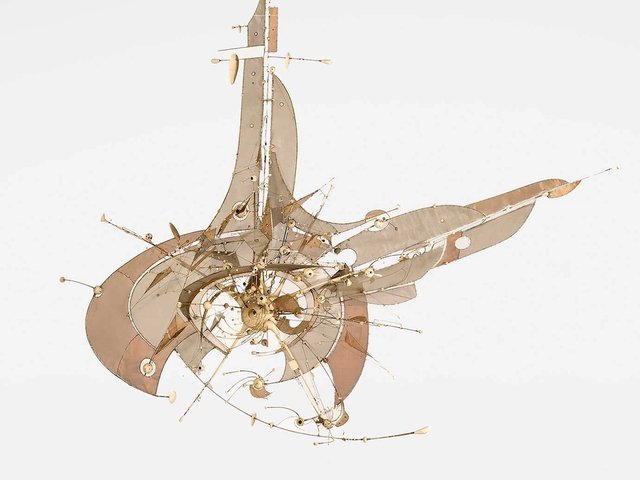

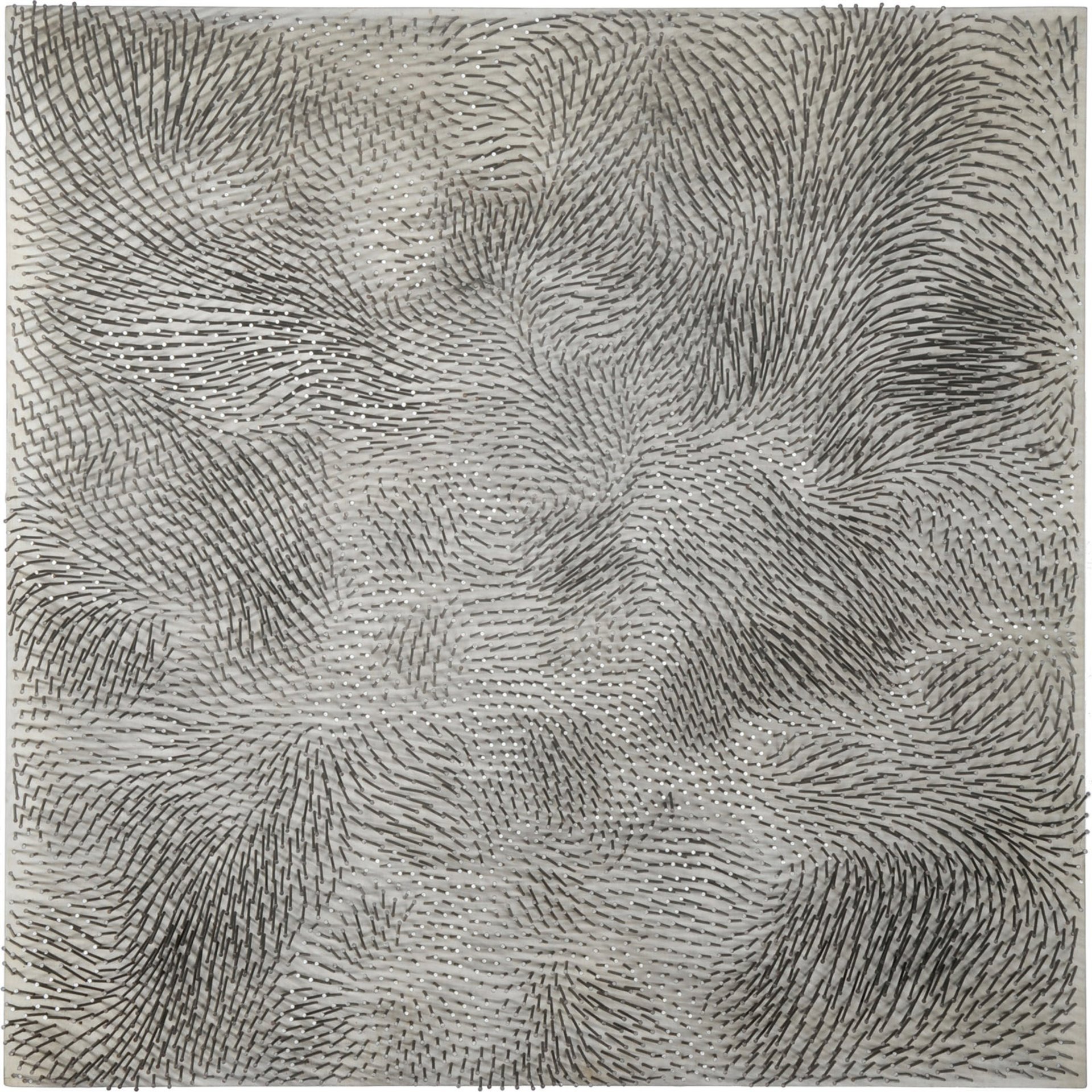

Strömung by Günther Uecker (1972) is on show at Beck & Eggeling International Fine Art Uecker: Beck & Eggeling International Fine Art

Group Zero

Over the past decade, increased US interest has boosted the market for the so-called Group Zero, formed in Dusseldorf in 1957, says the London-based dealer James Mayor. It was an exhibition at New York’s Sperone Westwater in 2008—nearly three decades after the last dedicated show in the Big Apple—that “woke up the Americans to Zero”. Valuable exposure has continued with the Guggenheim New York’s show ZERO: Countdown to Tomorrow in 2014-2015 and other major exhibitions in Amsterdam, Berlin and Istanbul in the past decade.

The works of Jan Schoonhoven and Günther Uecker are the most expensive because they are the most recognisable, Mayor says. At Tefaf, Beck & Eggeling’s stand will contain a trademark nail work by Uecker, while Borzo Gallery is showing a 1970 papier-maché relief by Schoonhoven.

Few artists have achieved more in the group than the Zero co-founder, Otto Piene, whose works Mayor believes are undervalued. “Piene will be seen as one of the giants of post-war art because of his philosophy and his contribution to art and technology,” he says. “He is the father of art and technology because he was doing it decades before anyone else.”

The major names aside, quality can be found for more modest sums among the less established of the group, such as the Swiss sculptor Christian Megert, who works with mirrored glass. “The close collaboration and thought process that was going on between these lesser known artists did produce some extraordinary work,” Mayor says.