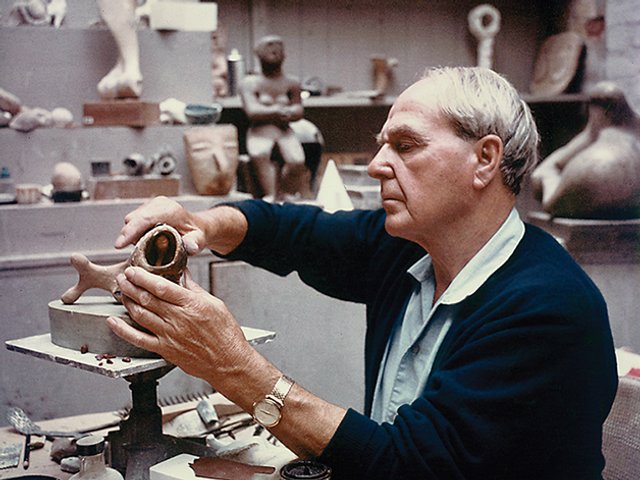

Henry Moore served in the First World War before being gassed during the Battle of Cambrai and sent home to convalesce. Two thirds of the men in his regiment were killed in the same battle. The broad-rimmed Tommy helmet and the German Stahlhelm, with its distinctive side air vents, along with the many hours he later spent amongst the Wallace Collection’s extensive hoard of helmets and armour, directly inspired many of the British sculptor’s works in Henry Moore: The Helmet Heads (until 23 June; £11 online, concessions available). The exhibition intermingles examples from the museum’s collection with Moore’s helmet- and armour-inspired bronze sculptures, maquettes, drawings and prints. It it easy to see why Moore was attracted to these highly sculptural, hand-worked military objects, such as a 15th-century sallet from Milan or a 16th-century full armour from Germany. Among the smaller sculptural highlights are a beautiful bronze horse from 1923 with its hind lowered in an unusual gait, and Maquette for Atom Piece (1964), with a highly polished helmet-shaped top contrasting with a darkened lower section. The final room contains the seven sculptures from the Helmet Head series (1950-75) with the first from 1950 clearly adorned with elements copied from those distinguishing Stahlhelm vents.

The naked body is given a scrutinising examination in The Renaissance Nude at the Royal Academy of Arts (until 2 June; tickets £14, concessions available). The 90 works on show are arranged by broad themes, each a reason used by Renaissance artists to disrobe their subjects. In one section, the 15th century return to classical mythology sees Luca Signorelli paint taut male posteriors, while elsewhere a painstakingly detailed anatomical study by Albrecht Dürer might have been made under the guise of edification. There are multiple depictions of Saint Sebastian, who stands confidently in a loin cloth in a scene by Giovanni Battista Cima da Conegliano, then later seated by Bronzino, in a portrait blurring the lines between the sacred and profane. Mercifully this show avoids the urge to shoehorn in a #Metoo moment, allowing the relatively limited manner in which naked women are represented (either as idealised beauties or demonic witches) to speak for itself. A 1508 engraving by Giulio Campagnola is, however, a welcome respite, showing a woman pleasuring herself, a subject which even today raises eyebrows. That nudity fascinated Renaissance artists should come as no surprise. Naked bodies hold our attention in a way few other subjects can, and judging by the crowds at this exhibition, little has changed in 500 years.

Head down to see the “Lost Caravaggio” at Colnaghi gallery today or tomorrow (until 9 March; free) before it goes off to auction at La Halle aux Grains in Toulouse in June. The painting of Judith Beheading Holofernes was discovered in an attic in Toulouse in 2014 and two years of authentication work followed, as well as a 30-month export ban placed on the canvas by the French government. The ban was partly to give the Musée du Louvre the option of buying the work, which it eventually declined. For more on this story, see Attic to auction: a timeline of the 'Lost Caravaggio'.