Joan Miró photographed in 1935 Photo © Corbis via Getty Images

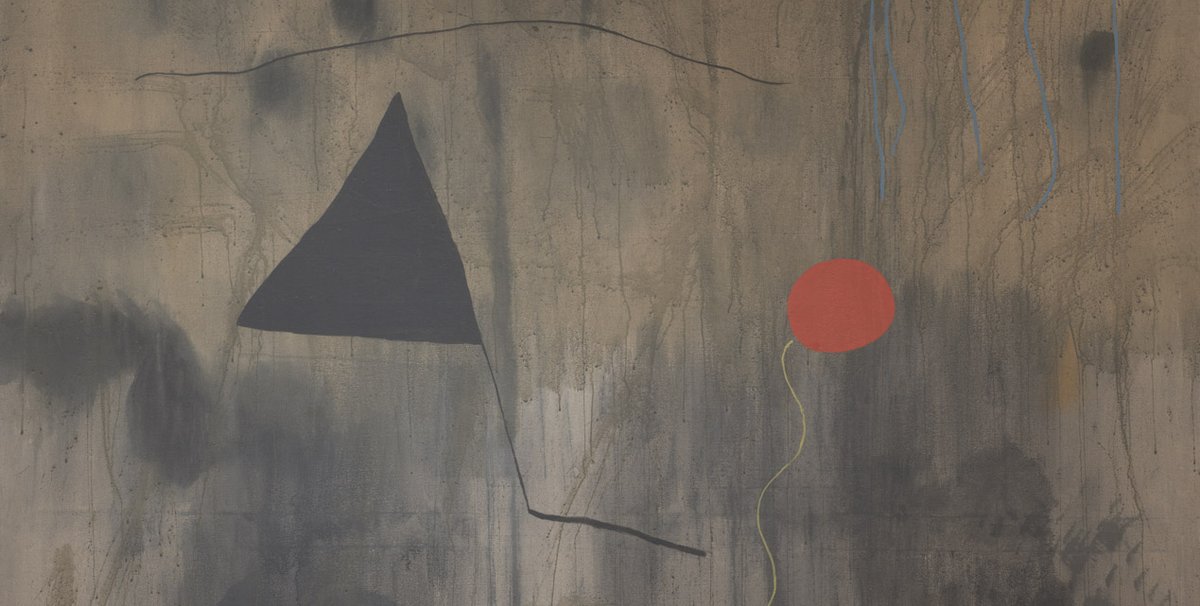

The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) has dug into its extensive holdings of pieces by Joan Miró for a show that demonstrates how one major work can be a turning point in an artist’s career. For the Spanish artist, it was the appropriately titled The Birth of the World, a large-scale painting he made in 1925.

In 1920, Miró experienced what he called the transformative “jolt” of his first trip to Paris, where he was introduced to avant-garde society and began absorbing the influences of other emerging painters and writers. That led to his first show in Paris in 1921 at the Galerie La Licorne. “Virtually no one came to it, Miró later recalled, and there were no sales,” says Anne Umland, the curator who organised MoMA’s exhibition, Joan Miró: Birth of the World. Deflated, the artist returned home to his native Catalonia and resolved to reinvent himself.

Critical to Miró’s osmosis over the next four years were his encounters with Surrealist poets and painters on subsequent trips to Paris, including the movement’s co-founder André Breton. Absorbing their fascination with dreams, fantasy and the unconscious, he began churning out a new body of work. “You and all my writer friends have given me much help and improved my understanding of many things,” the artist wrote to the poet Michel Leiris in the summer of 1924 from his family’s farm in the Catalan village of Montroig.

Miró’s next exhibition in Paris, at the Galerie Pierre in June 1925, proved a rousing success as well as a full-fledged Surrealist event, says Umland, with the signatures of all the young members of the revolutionary movement appearing on the show’s invitation.

Returning to Spain that summer, Miró had gained confidence while facing “the question of what he’s going to do next–how he’s going to keep up and surpass the high level he’s already set for himself”, the curator says.

The answer was The Birth of the World, which forms the centrepiece of MoMA’s exhibition. Through around 60 works dated from 1920 to the early 1950s, the show explores the creation of Miró’s pictorial universe in those decades–essentially, “how that great painter came to be”, Umland says.

The Birth of the World marks a turning point for the artist, introducing a working method divided into two distinct phases. Working spontaneously and giving rein to his unconscious, Miró variously dribbles, brushes and splashes paint onto the surface of an unevenly primed canvas, where it soaks in to varying degrees. Yet his next stage of painting is more calculated: relying on notebooks in which he sketched semiconscious surreal motifs, the artist paints pictographs atop the ground in a more meticulous calligraphic fashion. That mix of painterly spontaneity and calligraphic deliberation would persist in the artist’s work in subsequent decades, as museum visitors can attest by comparing works in the show.

Miró sets out to ‘surpass the high level he’s already set for himself’Anne Umland, Curator

The exhibition includes paintings, works on paper, collages, prints, illustrated books and ceramics. They range from early works such as Still Life II from 1922-23, in which three isolated objects floating in space can be clearly named, to Hirondelle Amour of 1933-34, where the calligraphic impulse yields actual written words, to Mural Painting of 1950-51, in which a frieze of figures measuring almost 20ft-long are thought to evoke a bullfight.

“Later in life Miró was encouraged to go back to many of his pictures and name the components,” Umland says. “But what’s really wonderful about them is that the shapes can mean different things in different works.”

The show is also a taste of MoMA’s planned uptick in exhibitions based mostly around its permanent collection, which will be a top priority when the museum opens its new spaces in September.

• Joan Miró: Birth of the World, The Museum of Modern Art, until 6 July, supported by the Kate W. Cassidy Foundation and Sue and Edgar Wachenheim III, among others