Women in all their fleshy, dimpled glory were the calculated focus of last night’s contemporary evening sale at Sotheby’s, which fielded its highest ever proportion of female artists.

Almost 20% of the 66 lots offered were by women compared with 10.5% in the equivalent sale in 2018 and 8.3% in 2017.

Head of sale Emma Baker took the bold decision to front load the auction with several women in the multi-million-pound bracket. As a result there were hits and misses. Expectations were high following the British artist Jenny Saville’s record result at Sotheby’s last October, but her nine-foot fleshy canvas of a woman’s back, Juncture (1994), elicited just one bid, selling over the phone to its guarantor for £4.8m (£5.4m with fees) against a brave estimate of £5m-£7m.

According to Baker, the punchy estimate took into consideration “the movement in Saville’s market” after Propped (1992) sold for £9.5m in October to become the most expensive work by a living female artist at auction.

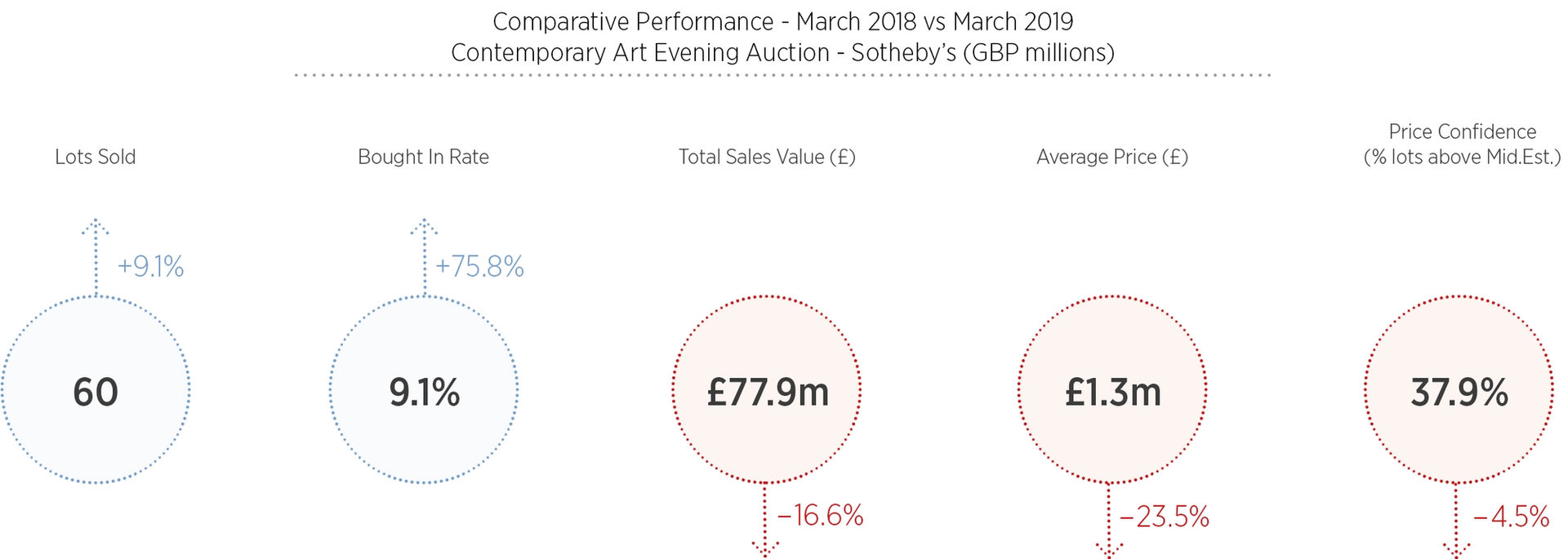

ArtTactic's analysis of Sotheby's auction shows total sales dropped 16.6% to £77.9m from the 2018 equivalent sale Courtesy of ArtTactic

There were records for another British woman, Rebecca Warren, whose bulbous bronze, Fascia III (2010), saw bidding from four parties, selling for £450,000 (£555,000 with fees; est £250,000-£350,000) and the Nigerian artist Toyin Ojih Odutola, whose evening auction debut fetched £200,000 (£250,000 with fees).

Both artists have enjoyed recent critical success: Odutola had her first solo museum exhibition in New York at the Whitney in 2017-18, while Turner Prize-nominee Warren showed at Tate St Ives last year, her first major UK solo museum exhibition in eight years.

“The most telling aspect of their success at auction is that for these artists, it followed their institutional engagement. We’re often wary of when the opposite occurs. These days we forget that this is the natural course by which careers, and then markets, develop,” says Adam Sheffer, the vice president of Pace Gallery.

Apart from Saville, the other woman to make it into the top ten was Agnes Martin. Female minimalists are in the ascendency, and her inoffensive pastel-hued painting sparked bidding from four bidders, selling for £2.3m (£2.8m with fees; est £1.8m-£2.2m) over the phone to a US client.

Sotheby’s may have tried to redress the gender balance of these evening sales, which typically only include one or two works by women (last week, there were none in the evening sales of Impressionist, Modern and Surrealist art). But in the end, the night belonged to men, most of them white and most of them dead. Not the most expensive, but the most stunning among them was Lucian Freud’s tender portrait, Head of a Boy (1956), which sold to an anonymous bidder in the room for £4.9m (£5.8m with fees) against a wide-ranging estimate of £4.5m-£6.5m.

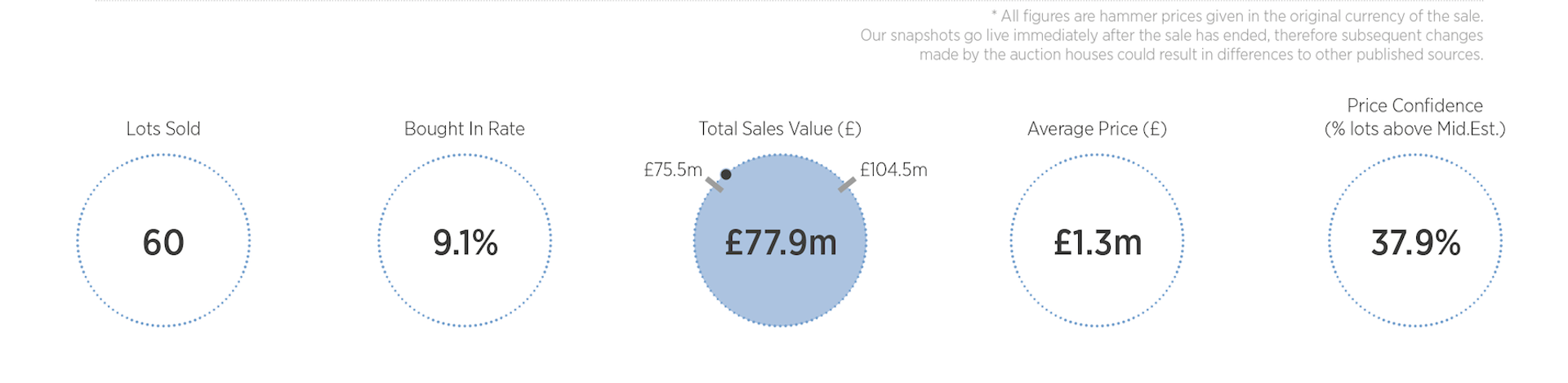

The average lot price was £1.3m hammer last night according to ArtTactic's research Courtesy of ArtTactic

It was an auction debut for the painting, which had hung at the bohemian Luggala estate in Ireland for more than 50 years. The sitter was a 16-year-old Garech Browne, the wealthy Guinness heir and patron of the Irish arts who died last March aged 78.

The American painter Jean-Michel Basquiat dominated the evening in terms prices. Apex (1986) was the only work to break the $10m-dollar mark, selling for £8.2m with fees (overall, the average price of lot was down 23.5% on last year to £1.3m). Two 1987 works on paper from the collection of the late Singaporean architect Louis J. C. Tan at least doubled their estimates, selling for £925,000 (£1.1m with fees) and £825,000 (£1m with fees).

Auctioneer Oliver Barker noted after the sale that US clients “responded well to the American material”, with bidding often rising in £25,000 increments–“which is very American”, he said.

The prospect of the looming Brexit deadline of 29 March had no significant impact on the sale, Barker observed. “The contemporary art market is more of a dollar-based market,” he said, adding that “people might be thinking of shipping their art” ahead of the deadline.

Overall, the sale made £77.9m (£93.3m with fees; estimate £75.5m-£104.5m), down 16.6% on last year. Flabby at times, it felt as if Sotheby’s had cast the net wide, but with a robust sell-through rate of 91%, the auction house worked hard to keep the money flowing. As the London art adviser Nazy Vassegh noted: “They did well to reduce reserves to get more works sold in a price sensitive market.”