Twenty years after the Washington Principles on Nazi-Confiscated Art were endorsed, we have reached a crossroads when it comes to Holocaust-related restitution. I helped bring this issue to light in 1998 when I gave the New York Times correspondence describing the Nazi theft of Egon Schiele’s Portrait of Wally (1912), then on loan from Vienna’s Leopold Museum to the Museum of Modern Art. The resulting furore prompted Austria to pass groundbreaking legislation mandating the return of Nazi-looted art in state collections.

Now “Nazi-looted art” has become a journalistic catchphrase frequently applied with scant basis in fact. In November 2013, newspapers and magazines around the world trumpeted the discovery of 1,500 Nazi-looted artworks, said to be worth over €1bn, amassed by the German dealer Hildebrand Gurlitt. None of this was true. Much of Gurlitt’s art had been purchased legally and the remainder comprised chiefly works on paper of little value. In the end, the case led to the restitutions of just six paintings, the discovery of at least one fake and a great deal of ambiguity.

Many works of art do not have complete provenances, particularly drawings, watercolours and prints. Even if we determine that a persecuted collector owned a particular work in 1925, that does not mean he or she still owned it when the Nazis came to power: art transactions were not always recorded, and the circumstances of persecution, emigration and the war itself caused a lot of paperwork to be lost or destroyed.

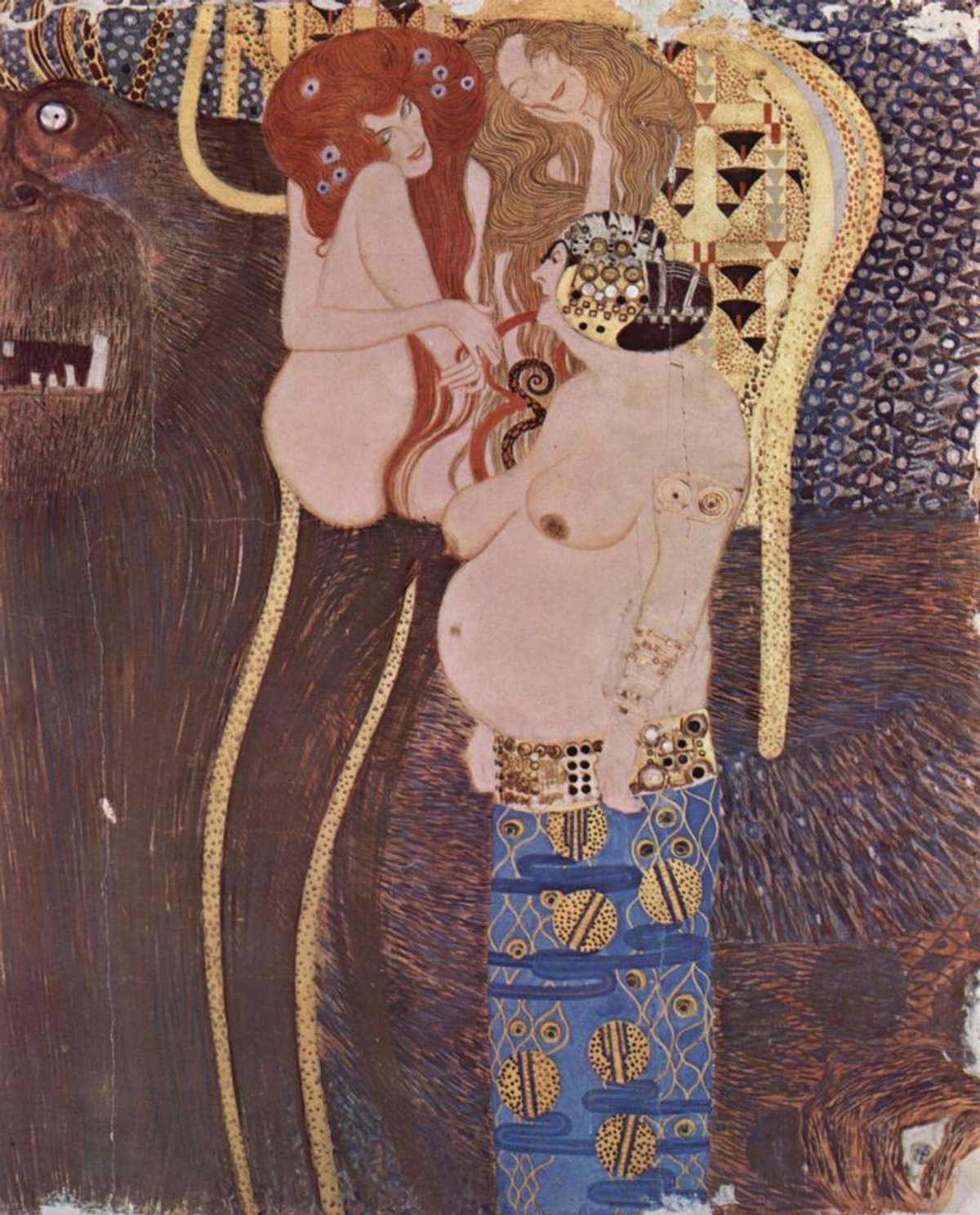

Therefore, the rush to judgment can lead to errors, as happened in 2000, when Austria restituted Gustav Klimt’s Apple Tree II (1916) to the wrong family.

Given that, with time, evidence vanishes and witnesses die, all Western nations impose some form of limitation on theft claims. Yet since many Holocaust claims would be time-barred under existing statutes, claimant advocates tend to recommend suspending the standard limitations. Unfortunately, this often means that works are judged guilty until proven innocent.

No one would disagree that restitution should be made when there is compelling evidence of Nazi theft. But sometimes the surviving evidence is inconclusive and people who purchased in good faith art that previously changed hands without protest have the right to be heard.

Back in 1998, Tom L. Freudenheim, then executive director of the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research in New York, warned that Holocaust-related art restitution was becoming a “playground for ambitious politicians, hungry lawyers and sleuthing journalists.”

“I fear a new era of witch hunts,” he wrote in Artnews, “in which individual profit motives overtake our understanding of the real issue: the massacre of millions of human beings.”

What happened to those millions can never be made good. When it comes to Holocaust-era art restitution, it is wise to remember that two wrongs do not make a right.