Since the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, East German artists have struggled to find a place in the art history of a united Germany. For East German female artists, especially those who chose a medium other than painting, the fight for recognition has proved even tougher—just as it was during the years of the Cold War.

The curator Susanne Altmann is doing what she can to redress the balance. The Medea Insurrection, an exhibition opening this weekend at the Kunsthalle im Lipsiusbau in Dresden, will examine radical female artists who worked behind the Iron Curtain. Around half of the artists in the show lived in the German Democratic Republic (GDR) before the fall of the wall; the other half hail from other Eastern European countries including Romania, Poland and Czechoslovakia.

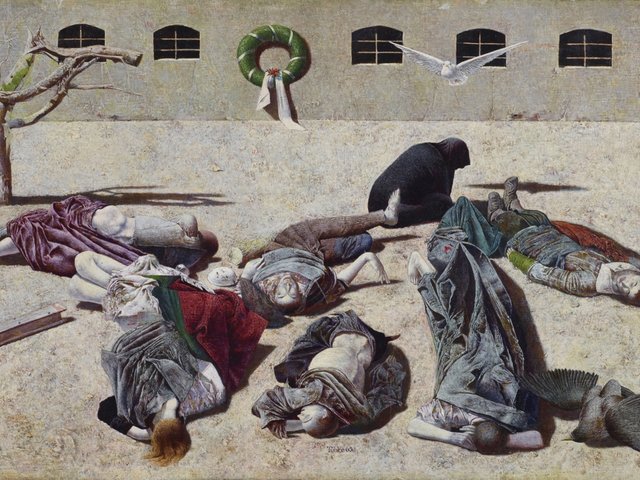

East German culture apparatchiks showed a preference for male figurative painters when choosing what went into museum collections. Those preferences still characterise the many exhibitions of East German art that have taken place since 1989.

“From a lack of freedom, a certain freedom emerges”

Christa Jeitner, who is represented in the show by her work Dreiflüglige Säule (1978, three-winged column), makes many of her pieces with materials such as rope and textiles. She says her creations were never considered “fine art” in East Germany, despite her focus on political themes, which were often carefully disguised. “It was considered handicraft or applied arts,” she says. “Whatever I showed in the GDR came under that label.”

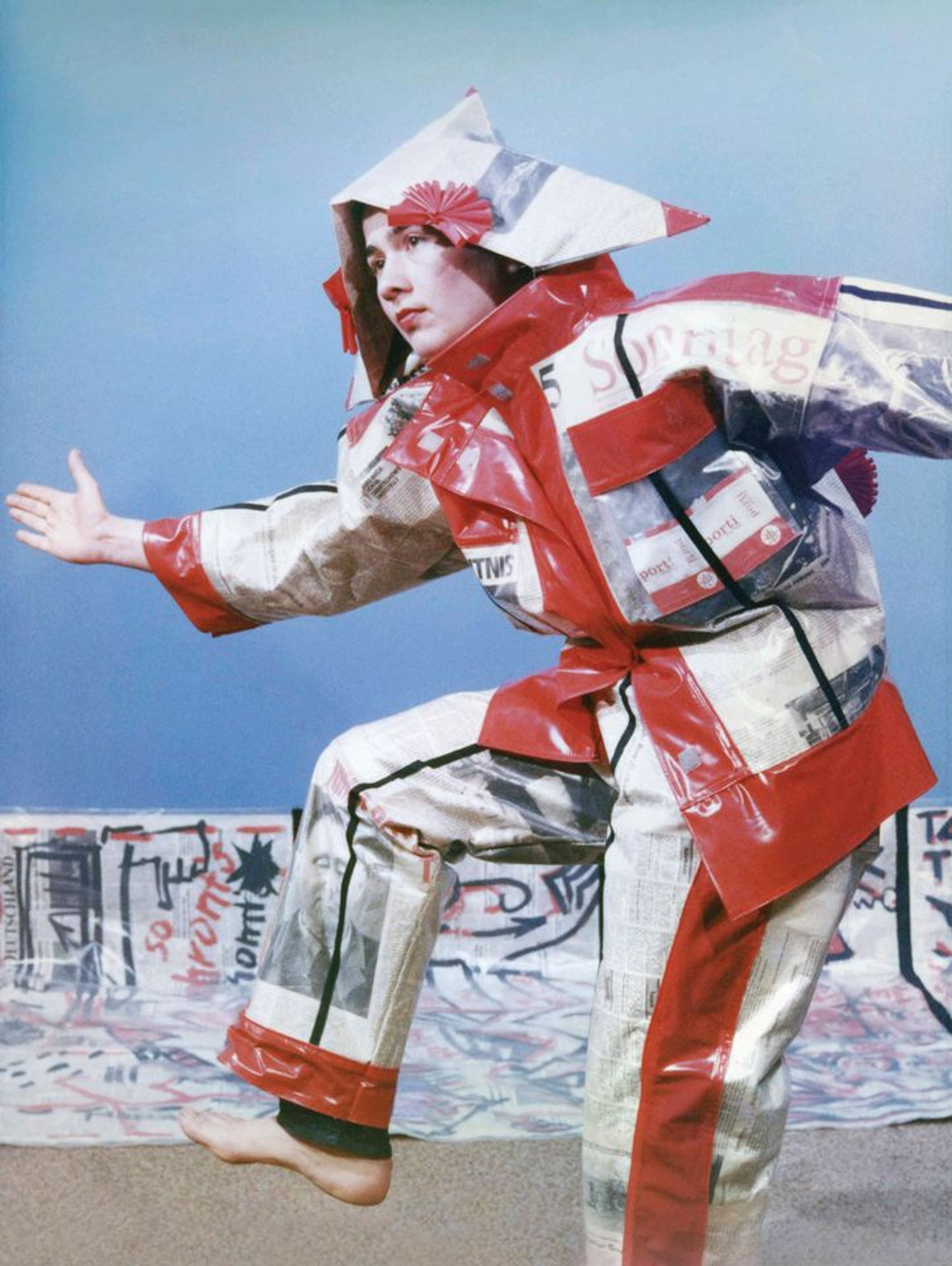

As well as painting and photography, the exhibition will feature performance, textiles and fashion, including designs by the 1980s radical East Berlin performance group Allerleirauh (on loan from the German Historical Museum). “Much of this is still written off as ‘subculture’, which is not an art-historical category,” Altmann says. “Even within the subculture, the men were dominant,” she says.

She adds that women artists were often more radical—perhaps because they were working so far under the official radar that they could take greater risks. “From a lack of freedom, a certain freedom emerges,” she says. Times are changing, and the show includes works by artists such as Geta Bratescu and Natalia LL, who have recently gained international acclaim.

Monika Andres’s Name, Stadt, Land (1988) © Monika Andres

Not all the artists escaped the long arm of the state: among those in the exhibition, Gabriele Stötzer was imprisoned as a dissident and faced years of surveillance by the Stasi, while Cornelia Schleime was banned from exhibiting in East Germany and fled to the West in 1981.

Jeitner, too, was banned from exhibiting in the late 1970s. For her, the Dresden show is of immense importance. Much of the art it showcases, she says, “could only be displayed locally or in group shows, whether publicly, unofficially, illicitly or just privately in the studio” before the fall of the wall. “This exhibition is a first chance to get to know the unofficial art of others.”

The exhibition is sponsored by the German-Czech Future Fund and the Women in Europe Foundation, among others. A catalogue including an essay by Altmann accompanies the show.

• The Medea Insurrection, Kunsthalle im Lipsiusbau, Dresden, 8 December-31 March 2019