Despite showing work alongside each other in the early 20th century, Paul Klee and Emil Nolde somewhat differed in style and ideology. Klee fled Nazi Germany for Switzerland; Nolde was an early, zealous member of the Nazi party who considered himself the emblematic German painter (after being labelled a “degenerate” artist, he even wrote to the Reich’s minister of propaganda, Joseph Goebbels, to argue this). Klee’s work is neat and measured; Nolde’s is freer and expressive.

But an extensive new survey of Nolde’s career, at the Zentrum Paul Klee in Bern, views his work through three thematic lenses that link his interests to those of Klee: the grotesque, the fantastic and the exotic. “[The two artists] have really different approaches, but they were interested in the same topics,” says the show’s curator Fabienne Eggelhöfer.

The exhibition also looks at their personal connections through correspondence. While the two artists did not influence each other’s practice, they collected each other’s work, and maintained a friendship up until Klee’s death in 1940.

Most of the 170 works on show are loans from the Nolde Foundation, and include pieces never before publicly exhibited. “I’m hoping that [visitors] can discover another Nolde—not the flower and landscape Nolde—and also learn how an artist’s [...] own pictorial language [evolved],” Eggelhöfer says.

• Emil Nolde, Zentrum Paul Klee, Bern, 17 November-3 March 2019

Nolde's road to artistic expression

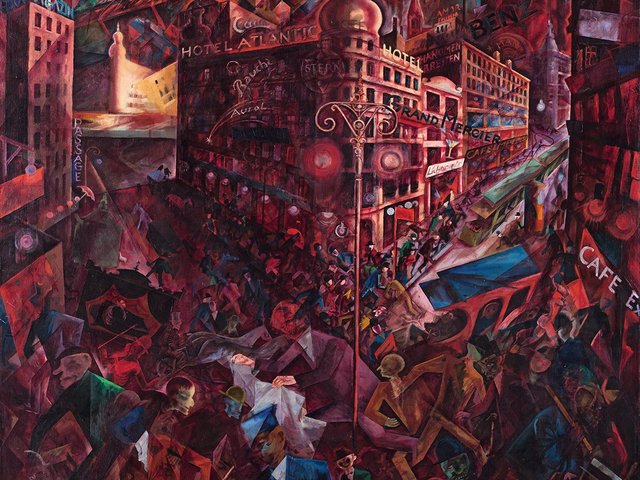

Coffee-House Visitors, 1911 © Nolde Stiftung Seebüll. Photo: Elke Walford and Dirk Dunkelberg

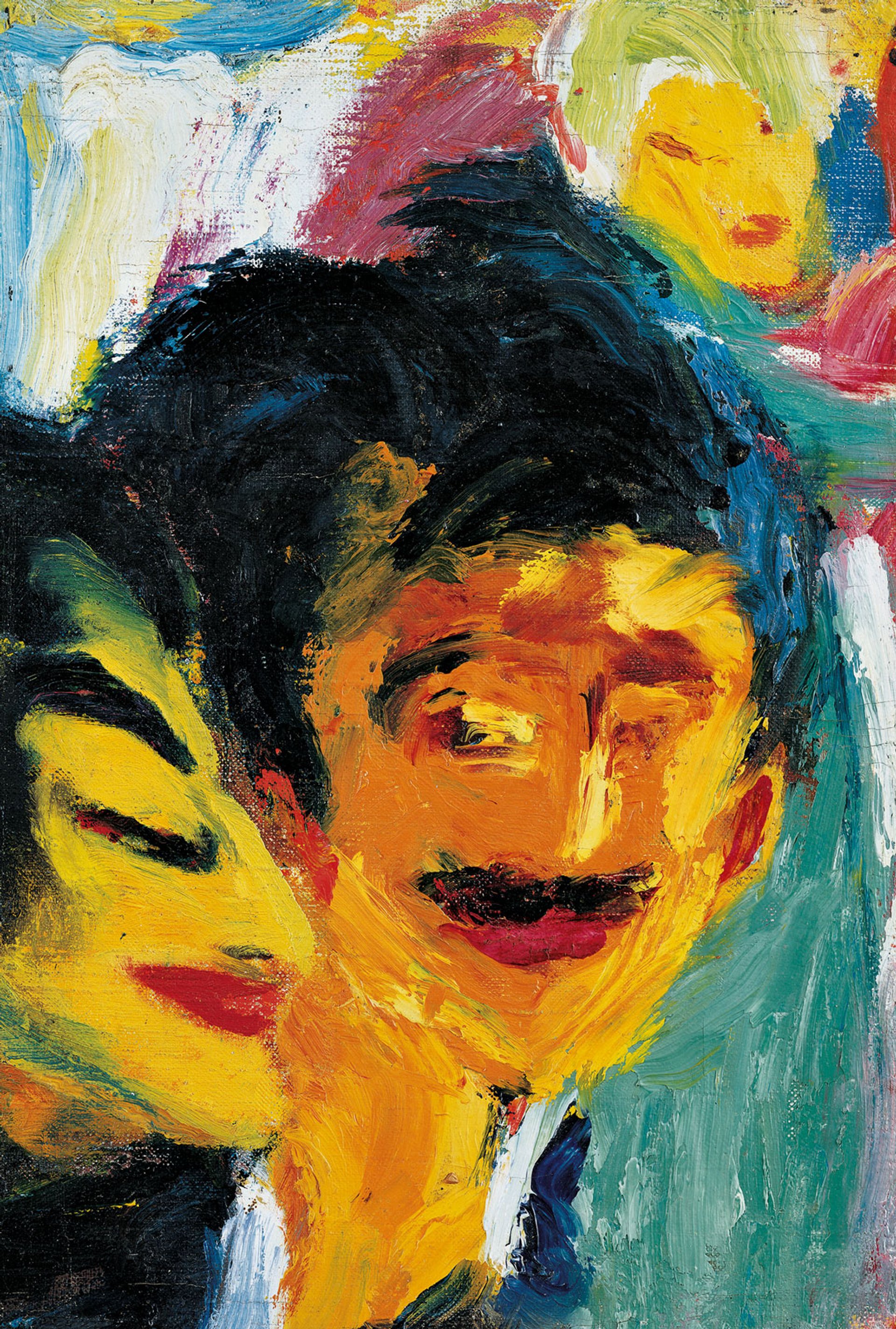

1 The grotesque

“The starting point for [Nolde] to find his own pictorial expression was the grotesque,” says the curator Fabienne Eggelhöfer. “That was one way he could escape from nature.” Sketches and paintings based on Nolde’s visits to Berlin theatres and nightclubs in the 1910-20s show distorted or mask-like faces, influenced by artists such as Honoré Daumier and James Ensor.

Exotic Figures I (Fetishes), 1911 © Nolde Stiftung Seebüll. Photo: Antje Zeis-Loi, Medienzentrum Wuppertal

2 The exotic

Nolde collected non-European artefacts; sketched objects in Berlin’s Royal Museum for Ethnology; and in 1912-13 visited the South Pacific. His still-lifes sometimes combine non-Western and European objects. “He always said, ‘Even though I have this fantastic motif or this exotic motif, I stay rooted in the German tradition,’” Eggelhöfer says.

Fat Woman with Mythical Figure, date unknown © Nolde Stiftung Seebüll. Photo: Elke Walford and Dirk Dunkelberg

3 The fantastic

“For me, the fantastical was a liberation for him towards his own artistic expression,” Eggelhöfer says. Nolde did not rely on what he saw; for example, he described strange daydreams he had when visiting small villages in the Jutland peninsula, after which he began to make watercolours reminiscent of works by Francisco Goya.