Elke Kupfer, an artist who produces large-format collages using plastic bags, was forced out of her studio in the Kreuzberg district of Berlin in 2015. The building on Erkelenzdamm, a former soap factory converted into artists’ studios, had been bought by the Swedish property company Akelius, which has since renovated it to serve as its Berlin headquarters.

Kupfer spent a year looking for a new studio that was both big enough for her work and affordable. “I couldn’t find anything,” she says. “Sometimes I looked at three places a day. It was very stressful.” After reducing her minimum size requirement, she finally found a studio in the Neukölln district. “But I pay three times as much rent and can’t work in large formats there.”

Her story is not unique. Since the 1990s, Berlin has served as a magnet for artists drawn by cheap rents, large empty buildings, a vibrant subculture and a hip, liberal atmosphere. It ranks as the most important centre for art production in the world after New York. Olafur Eliasson, Ai Weiwei and Alicja Kwade are among the prominent artists with studios here.

Local residents stage a protest in Berlin © Adam Berry/Getty Images

But for the past ten years, the city has been in the grip of a property boom, with spiralling price increases threatening its allure for artists. In 2017, Berlin had the fastest-growing real estate prices in the world, up 20.5% in a year, according to the property consultancy Knight Frank.

For the city’s estimated 8,000 fine artists, the situation is particularly acute because the majority live in poverty. A recent survey of more than 1,700 Berlin artists by the Institute for Strategy Development found that only one in ten earn enough to live on from their artistic work. Around one in five are paying between 50% and 100% more for their studios now than in 2010.

“It’s not just the studio rents that are disastrous for artists,” says Martin Schwegmann, the head of the BBK (Professional Association of Visual Artists in Berlin), a city-funded agency that secures studio space for artists. “It’s also the fact that living space is in short supply and expensive. Prices are shooting up. Artists have a tendency to contribute to gentrification and price appreciation. We need to ensure that this doesn’t lead to them being driven out of the city.”

In some cases, it’s already too late. Katrin Plavcak, a painter from Vienna, moved to Berlin in 2002 and found a studio and flat quickly. But she was evicted from the artists’ community based in Post Ost, a former post office in the Friedrichshain district, when it was purchased by an investor in 2016 and turned into a centre for technology start-ups. Plavcak decided to return to Vienna when she found an affordable studio and home there.

“It’s sad,” she says. “I felt very happy in Berlin and I had a great community in Post Ost. I would have stayed if I could.”

Gentrification threatens exactly what brought artists—and many others—to Berlin in the first place: an unostentatious, dilapidated trendiness and edgy charm that in 2003 prompted its mayor, Klaus Wowereit, to sum up the city as “poor but sexy”. The population is increasing by 40,000 a year and housing construction is not keeping up. The current mayor, Michael Müller, is even weighing a ban on property purchases for foreigners, to protect affordable living space. “We are no longer quite as poor, but still sexy,” he said in a recent newspaper interview.

In central Berlin, redevelopment and soaring rents have led to the loss of artists’ communities, such as Post Ost Boris Joens

Berlin’s gentrification follows a pattern familiar to cities such as London and New York. “The artists arrive,” Kupfer says. “The property appreciates in value. Then the artists are pushed out, and the reason why the people came in the first place is no longer there. We are going in the same direction as London in terms of prices, and I think that is a great pity.”

The Berlin Senate subsidises workspace rents for artists of all disciplines (theatre, dance, music, fine art) to the tune of around €7.3m a year and invests a further €7m in acquiring, converting and renovating suitable spaces for the arts. The BBK secures studios for artists, which they can rent for €4 per square metre—significantly lower than market rates.

Around 900 subsidised studios are available to rent, and Schwegmann estimates that 4,000 more will be needed in the medium term. For each studio that he lets, he receives on average 10 applicants. In the case of space in a particularly desirable location such as Kreuzberg, there can be as many as 90 applicants.

Perhaps unsurprisingly given the steep price rises and limited availability in central parts of the city, Schwegmann is looking for creative pastures beyond the borders of the S-Bahn, the commuter train route that circles the city. The BBK’s recent masterplan, which aims to create 2,000 new studios by 2020, proposes establishing “art campuses” on the fringes of the city. These could be either whole new complexes or redeveloped “Plattenbau” constructions—the prefabricated concrete residential blocks built by communist East Germany.

Klaus Lederer, Berlin’s culture secretary, has made creating new space for artists one of his top priorities. But his hands are tied. Burdened with debt since the 1990s, the city government has already sold many publicly owned buildings, according to Boris Joens, a composer and performance artist.

“This should have all happened sooner,” Joens says. “Berlin’s arts and culture scene is a marketing tool for the city, but it can only survive if there is room for us to work. The masterplan is very ambitious and I am sceptical the targets will be reached.”

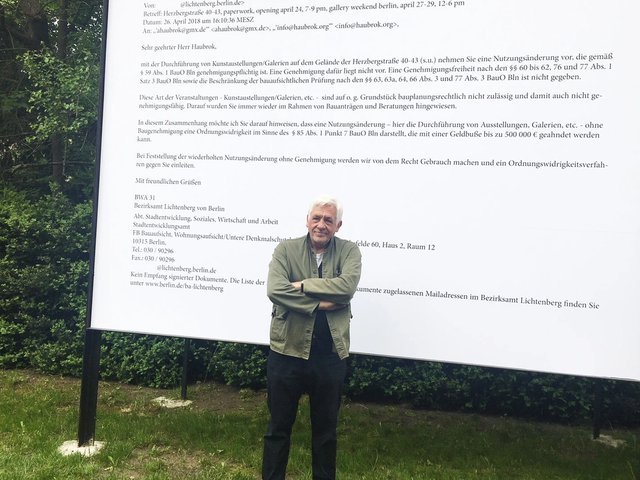

Joens is a founder of the Alliance for Threatened Studio Houses (Allianz Bedrohter Atelierhäuser) in Berlin, a network that protests against the disappearance of artists’ workspaces. Like Plavcak, he was evicted from Post Ost. He is now looking for a new studio with fellow artists who want to rent a large space as a group.

“There is nothing in the centre,” he says. “If you are lucky, you can still get something with the BBK programme. But those are one-off cases.”

As rents continue to rise, Joens, like many artists, is considering a step that would once have seemed unthinkable—a move to the suburbs.