Hans Ulrich Obrist, the artistic director of the Serpentine Galleries, asks a lot of questions. Ever since he published his first volume of interviews in 2004, hundreds of artists and cultural figures have been on the receiving end of his interrogations. But now, as the London institution hosts a major new show by the French artist Pierre Huyghe (until 10 February), we turn the tables on the super curator and let him face questioning by the artist whose works he is exhibiting. Here is what Huyghe was able to extract.

Pierre Huyghe: Why do you think you continue to do what you do?

Hans Ulrich Obrist: I believe in this idea of junction-making. We can only solve some of the big challenges of the 21st century if we go beyond the fear of pooling knowledge.

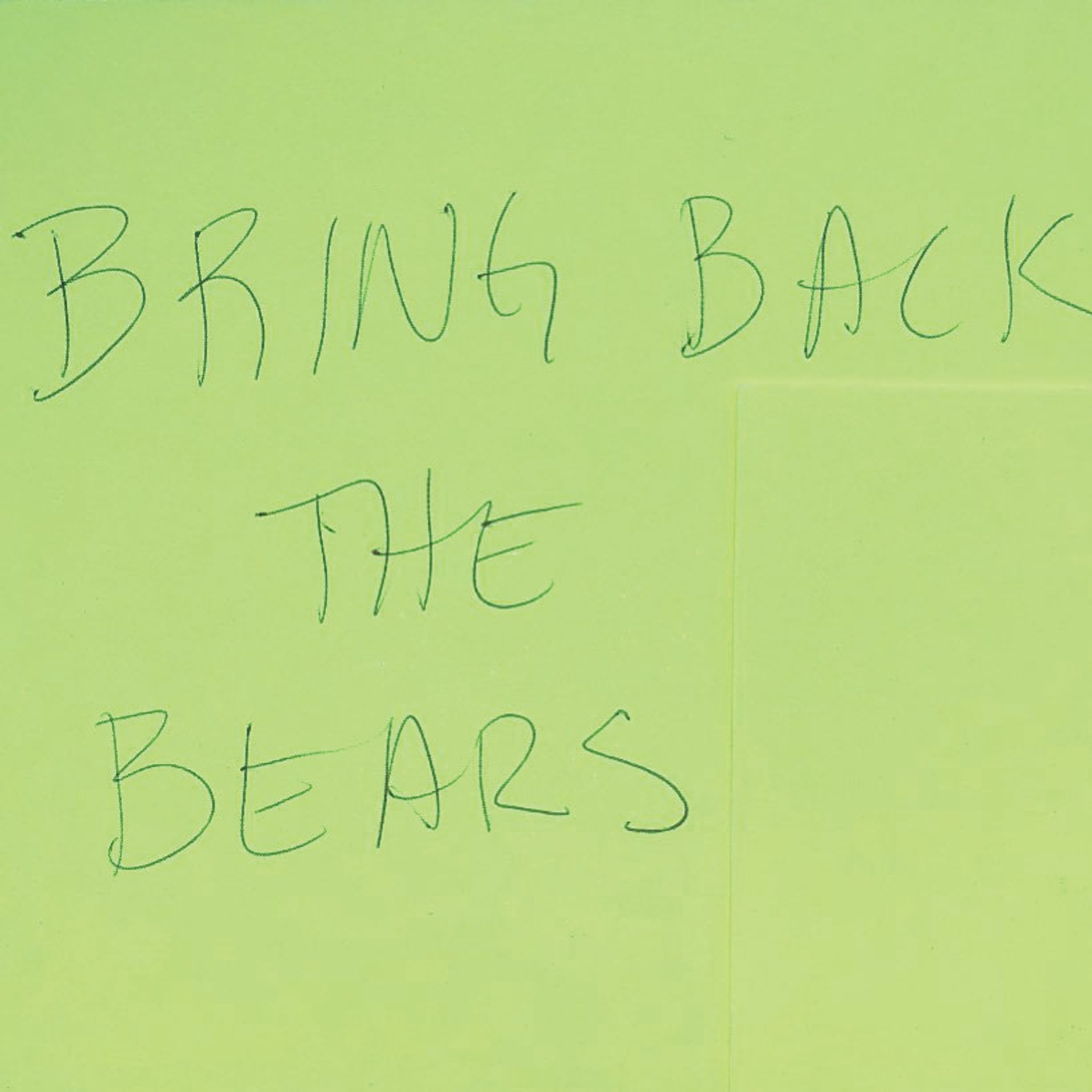

I want to continue because it’s urgent. It is a time of planetary crisis. [The artist] Gustav Metzger talked about extinction; not only the biological extinction of our species and our own demise, but also the disappearance of cultural phenomena. I want to resist extinction every day, be that through exhibition-making or through campaigning to save handwriting on Instagram.

A note by Rachel Rose, posted on Obrist’s Instagram account as part of his campaign to save handwriting Hans Ulrich Obrist/Instagram

I am also driven by the importance of memory. As [the British historian] Eric Hobsbawm always told me, we must protest against forgetting.

Enabling emerging practitioners to stage their first exhibitions also makes me continue to do what I do; working with artists over many decades, while at the same time always being open to new discoveries such as artists like Sondra Perry, whose first European museum show we organised at the Serpentine.

What would be a reason to stop?

The answer is a quote from [the Scottish artist] Douglas Gordon that became the title of one of my books: DON’T STOP, DON’T STOP, DON’T STOP.

If you could directly transmit what you imagine to another mind, what would that be? And in what way specifically would you transmit your imagination?

I think it would have to be hope and enthusiasm. As [the US poet Ralph Waldo] Emerson said: “Nothing great has ever been achieved without enthusiasm.”

What is the exhibition ritual in the 21st century?

[The UK artist] Richard Hamilton taught me that exhibitions are rituals that invent a new rule of the game, and/or a new display feature. A ritual is a series of actions regularly followed by someone, which brings us to DO IT. We did an exhibition made out of instructions and how-to manuals that has been interpreted and reinterpreted in 160 museums on all continents since 1993. More recently, it’s become part of the curriculum of the high school students in New York.

Hamilton’s friend, the architect and urbanist Cedric Price who, with [the British theatre director] Joan Littlewood, invented The Fun Palace, taught me that we need to go beyond the exhibition as simply a visual ritual and come up with more complete and holistic rituals that involve all the senses. This was the main focus of my exhibition A Stroll through the Fun Palace, which I curated for the Swiss Pavilion at the 2014 Architecture Biennale.

At the Serpentine, we feel it’s time for new experiments in art and technology. This spring we showed Ian Cheng, who used to work for you Pierre. Ian’s show BOB opened up a totally new ritual around an artificial life-form whose AI modes can power its behaviours for a whole lifetime. BOB stands for Bag of Beliefs and is sentient. It’s aware of you as the viewer, it can interact with you and you can influence its emotional life. It’s not interactive art, it’s art with a nervous system.

Of all of the people you have met, which of their ideas have you found the most stimulating in changing the way that we are, in any field?

I have been inspired by so many people. One example is the poet and writer Édouard Glissant, whom I met very regularly. He was my mentor and I think about him every day.

I find his “archipelagic thinking” vital in this time of fragmentation that we find new ways to think, to create new forms of interconnectedness and a sense of co-dependence. As he wrote: “Because, in the end, the idea [of an art institution] today is to bring the world into contact with the world, to bring some of the world’s places into contact with other of the world’s places… We must multiply the number of worlds inside our art institutions.”

What are some of your unrealised ambitions?

To do a big exhibition of Unrealised Projects. I have been archiving unrealised projects by artists and other practitioners for many years. It is the archive of Unbuilt Roads. It’s an incredible archive that includes the utopic, the forgotten and the censored; projects that lost public art competitions; projects that were too big or too small to realise. It also includes self-censored projects, those that we don’t dare to take forward, something that [the novelist] Doris Lessing talked to me about.

I would also like to complete an unfinished novel that I started when I was 18…

My partially realised project is to write and edit my diaries, but this keeps being interrupted. Finally, my unrealised show: I always dreamt of doing a show with [the US artist] David Hammons.

As told to Julia Michalska

• Pierre Huyghe, Serpentine Galleries, London, until 10 February