Jutting out over the river Tay, the ship-like concrete form of the V&A Dundee will finally open its doors on 15 September. More than ten years have passed since a proposal was first floated to bring exhibits from the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A) in London to Scotland’s fourth largest city, almost 500 miles away. The idea has evolved to match the big ambitions of Dundee—now home to Scotland’s most expensive museum, at £80m, its first dedicated to design and the only UK branch of the V&A outside London.

Despite the name, the V&A Dundee “is Dundee’s project”, says Mark Jones, the V&A’s director from 2001 to 2011. In 2007, officials at the University of Dundee approached the London museum to help transform the post-industrial city’s “very poor reputation in Scotland” through culture, he says. Dundee City Council backed the studies for a landmark new venue on the waterfront, where a 30-year, £1bn regeneration masterplan was already under way. The V&A committed its “content and advice” to an initial 25-year partnership, but no funding towards the capital or running costs. The Dundee museum also has an independent board of trustees (including the V&A’s current director, Tristram Hunt).

The museum’s founders looked to the Guggenheim Bilbao—and the success of the “Bilbao effect”—as a touchstone. The hope was that a “striking building by a significant contemporary architect” would “disrupt people’s expectations about the city”, Jones says. The Japanese architect Kengo Kuma won the international design competition in 2010.

It has been crucial, however, to develop “a compelling reason why the institution should exist, beyond the perception of a remarkable building”, says Philip Long, the V&A Dundee’s director since 2011. The museum’s “clear ambition” to enrich lives has “helped us through challenging times in the project”, he says. As costs spiralled, the original £45m budget was almost doubled and the opening was delayed by four years.

To counter scepticism at the use of public money “in a city of multiple deprivation”, a learning team was appointed to lead workshops and events in communities across Scotland, Long says. The programme reached an estimated 100,000 people by the end of March. “There’s an enormous amount of loyalty growing around the museum,” he says.

Unlike the Guggenheim Bilbao, where around two-thirds of the visitors are foreign, the V&A Dundee anticipates that 60% of its audience will live “within a 60-minute drive time”, a spokesman says. “A further 20% will come from elsewhere in Scotland, with the rest from UK and international markets.” Around 500,000 visitors are expected in the first year, settling down to around 350,000 in future.

The opening programme has been designed with Scottish sensibilities in mind. Inaugurating the 1,100 sq. m exhibitions gallery—the largest in Scotland—is the V&A show Ocean Liners: Speed and Style (15 September-24 February 2019), which was presented in London earlier this year. A section celebrating Scotland’s shipbuilding past will be expanded in Dundee.

At the heart of the museum is a free permanent display spanning 500 years of Scottish design history. Around 300 long-term loans—two-thirds from the V&A and one-third from collections around Scotland—will fill the 550 sq. m Scottish Design Galleries. Although it has no collection of its own, the V&A Dundee aims to serve as a national museum of design—an “overdue” addition to the Scottish museums ecosystem, Long says. Scotland’s “amazing design creativity” deserves recognition on a par with its visual arts scene, he adds.

Displays will also pay tribute to Dundee as the birthplace of the Beano comic and a hub for the video games industry, which saw it named the UK’s only Unesco City of Design in 2014. The title is a sign of a city that “is thirsty for change” and “is identifying itself more and more through its creative talent”, Long says. “There is a growing sense of confidence in Dundee that it is able to achieve its ambitions, and those ambitions are high.”

Curator's Pick

To create the new museum’s Scottish Design Galleries, curators first conducted an audit of the V&A’s collection in London. From 12,000 objects with a Scottish connection, they chose around 200 that are going on view in Dundee, alongside around 100 loans from collections across Scotland. Joanna Norman, the V&A’s senior curator of research and lead curator of the galleries, reveals the unexpected stories behind three of the exhibits.

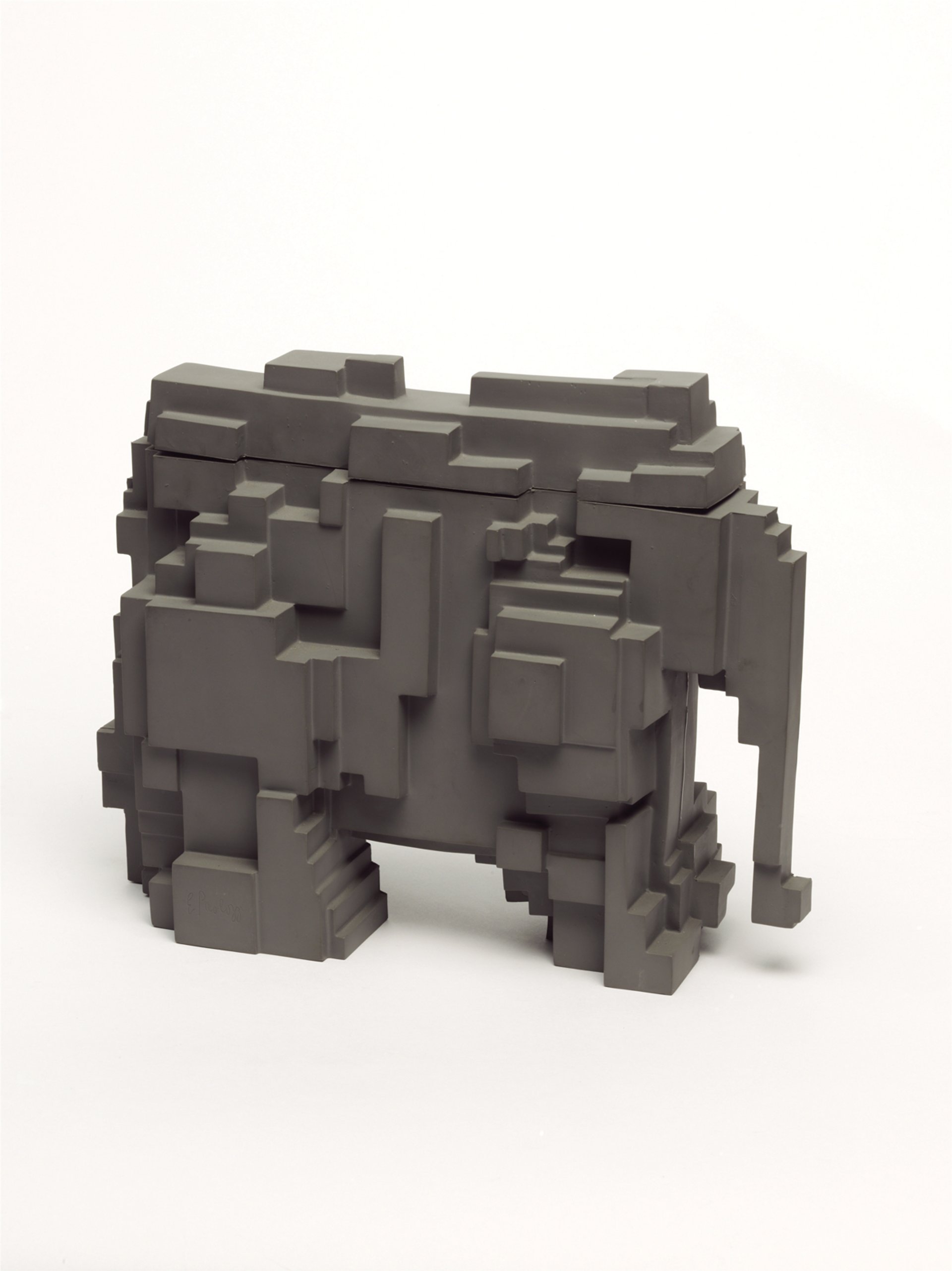

Eduardo Paolozzi’s elephant © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Eduardo Paolozzi’s elephant (1972), V&A

“This 30cm-high linoleum sculpture held catalogues for Nairn Floors. The firm was based in Kirkcaldy and for around 100 years from around 1870 was one of the world’s most successful producers of linoleum. Nairn commissioned Paolozzi to design this promotional case for catalogues; they were sent to architects to show them how important this product was—how clever it was in its design.”

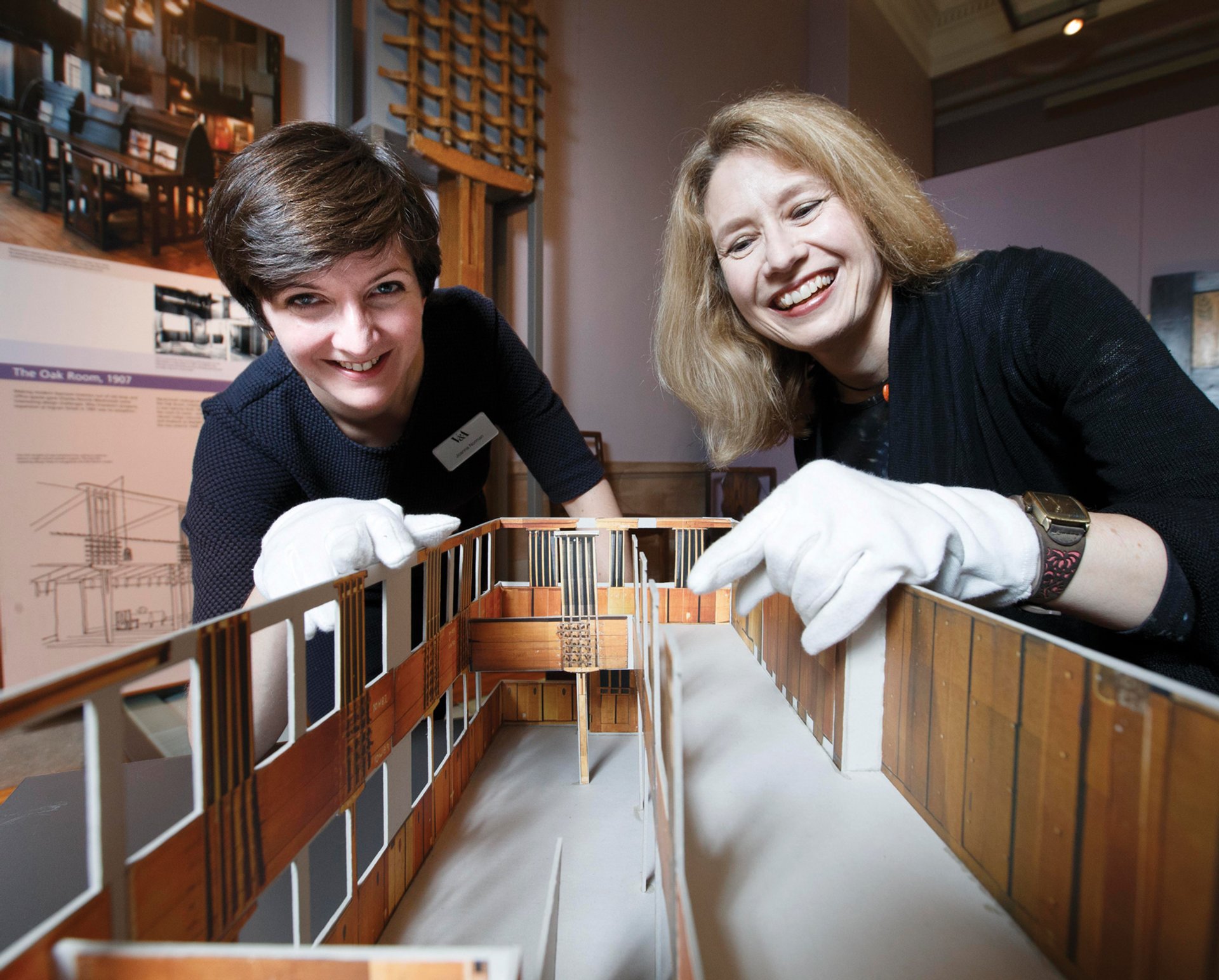

Charles Rennie Mackintosh’s Oak Room for Miss Cranston’s Ingram Street Tearooms (1907) Photo: Robert Perry

Charles Rennie Mackintosh’s Oak Room for Miss Cranston’s Ingram Street Tearooms (1907), Glasgow Museums

“It is unfurnished so you can really explore the details of his interior design—the way he orchestrates every element. He inset pieces of glass into the wood panelling so you have a band of colour. Three types of light fitting are carefully positioned so the room is very rhythmic. It shows him exploring design ideas that found fruition in the Glasgow School of Art library.”

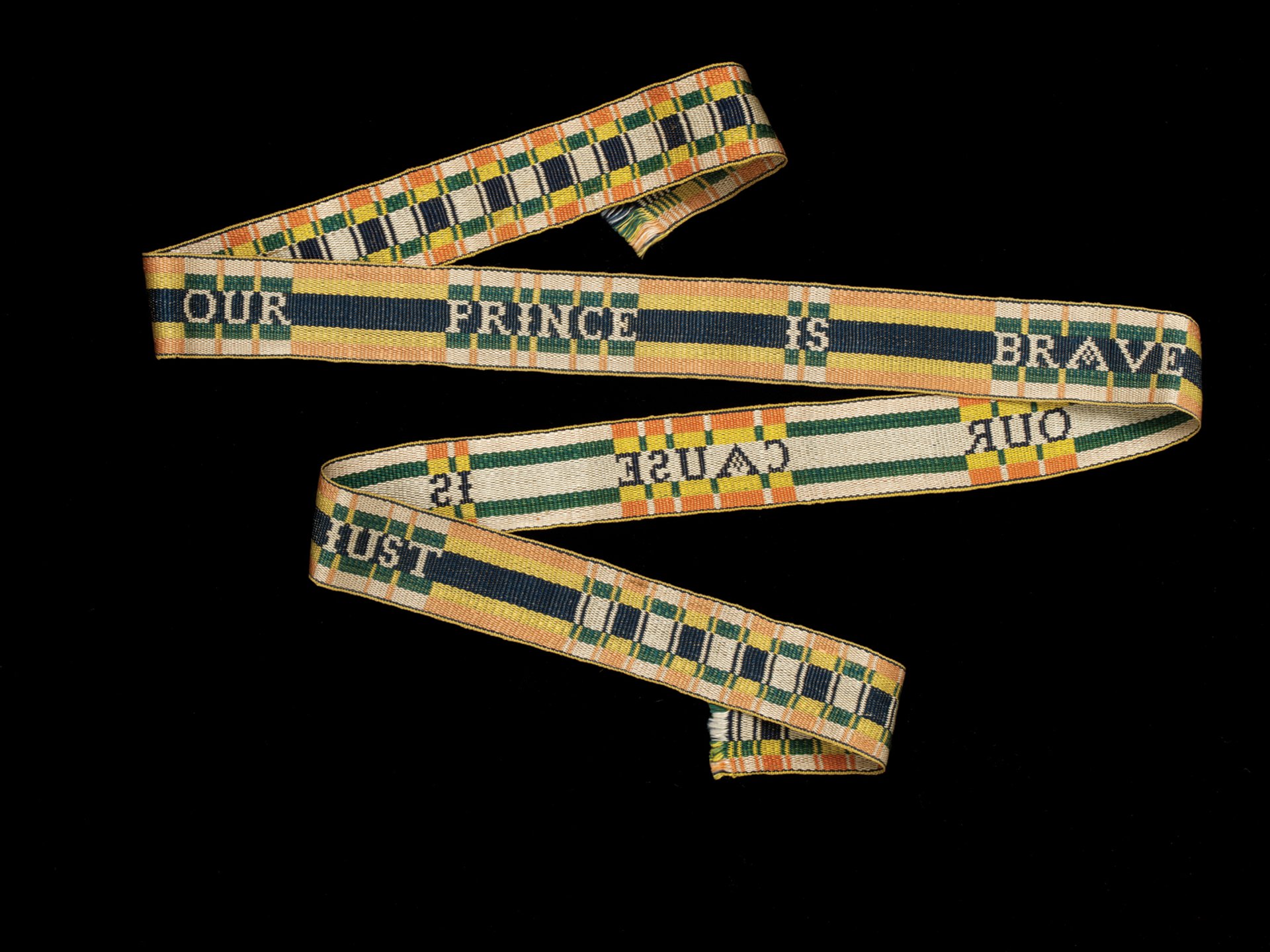

Jacobite garter (around 1745) © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Jacobite garter (around 1745), V&A

“It was originally one of a pair, woven with rhyming mottos. This says: ‘Our prince is brave, our cause is just.’ Because they were garters, they wouldn’t have been seen. They were private expressions of allegiance to a cause that was not just Scottish; it was across Britain and continental Europe. In 1748, the Gentleman’s Magazine described garters like this as ‘daubed with plaid and crammed with treason’.”