Gauvin Alexander Bailey, The Palace of Sans-Souci in Milot, Haiti (ca. 1806-1813). The Untold Story of the Potsdam of the Rainforest / Der Palast von Sans-Souci in Milot, Haiti (ca. 1806-1813). Das vergessene Potsdam im Regenwald, Deutscher Kunstverlag, 200pp, €14.90 (pb)

This short book is as fascinating as it is original. It can be assumed with some confidence that not many readers will be familiar with its central character King Henry I Christophe of Haiti, whose brief reign was marked, if not immortalised, by an extraordinary burst of building projects. Following the collapse of French rule in Haiti, he elbowed his way through chaos and carnage to become ruler of the northern half of the country in 1807, initially as president. Following his self-proclamation as king in 1811 he created a regime that was truly Janus-faced. On the one hand, it was a parody of Napoleon’s court (itself a parody of the ancien régime) complete with a constellation of nobles (four princes, seven dukes, 22 counts and so on), an elaborate hierarchy, sumptuous livery and a corps of African bodyguards delightfully known as the Royals-Bonbons. On the other hand, King Henry proved to be an energetic and enlightened if autocratic reformer, building hospitals, providing free health care, founding numerous schools, codifying the laws and promoting trade and manufacturing. His achievements won the praise of numerous contemporaries who observed them at first-hand, including Joseph Banks, President of the Royal Society. Alas, it all ended in tears. In October 1820, after a reign of just nine years, he shot himself (reportedly with a silver bullet) rather than face the insurrectionaries breaking into his palace.

Gauvin Alexander Bailey has served his subject wonderfully well. By dint of painstaking research, his meticulous scholarship has stripped away the many layers of myth, exaggeration and downright falsehood that accreted around King Henry’s life and times.

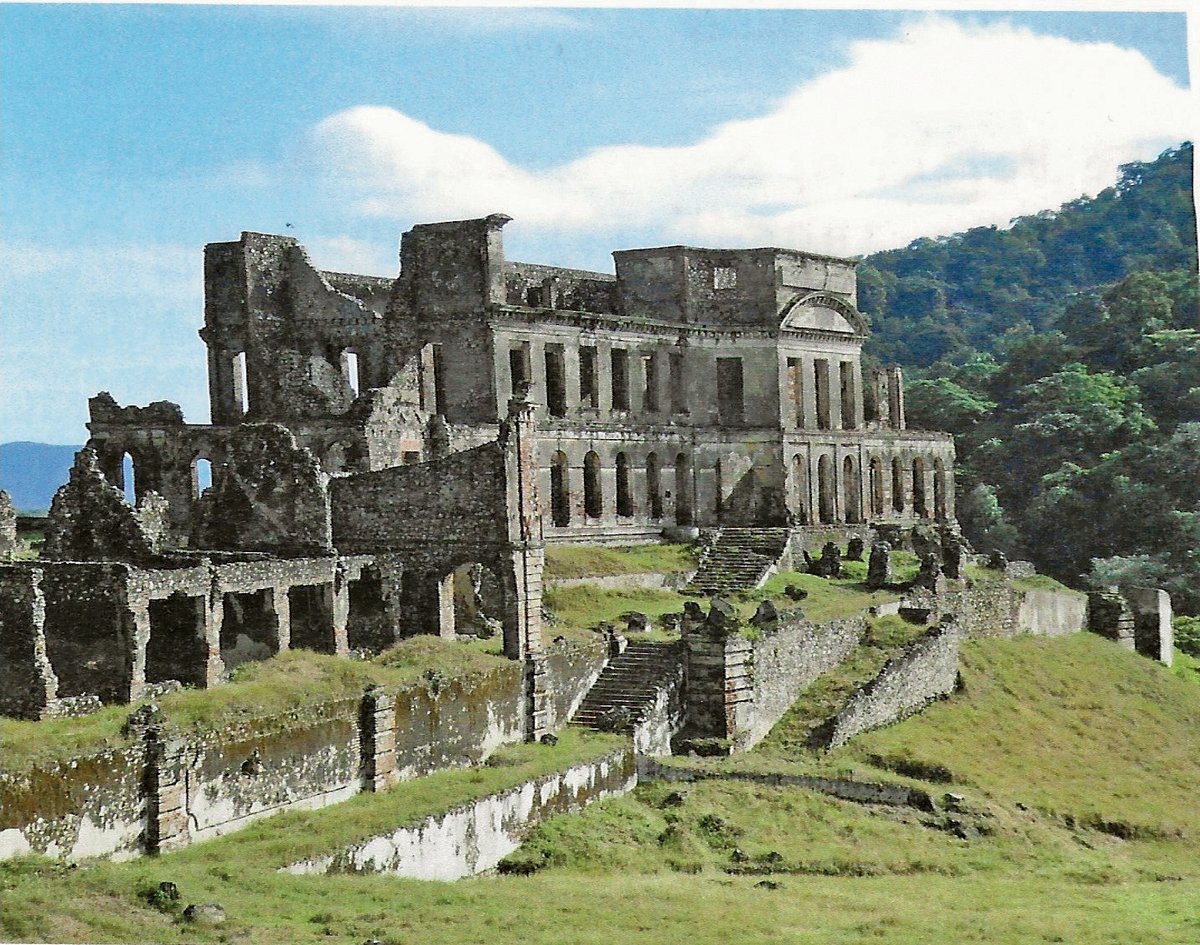

Two buildings stand at the centre of his account. The first is the gigantic Citadelle Laferrière, begun before Henry’s reign but essentially his creation. It is an indication of the literal and metaphorical hot-house in which he lived that this can be hailed as the largest fort in the Western Hemisphere. Also on a gigantic scale was the palace-building programme: nine urban residences and 15 rural châteaux (with names such as Délices-de-la-Reine). The only one to survive is Sans-Souci, probably but not certainly named after Frederick the Great’s much more modest creation at Potsdam. Stripped of all its opulent furnishings by Henry’s killers, only the ruined shell remains, although that is imposing enough. By dint of research of impressive depth and breadth, Bailey has been able to identify both the architects and their (mainly French) models of this amazing building spree.

A very good impression of what remains of the academy of Sans-Souci, and also of the Citadelle and other contemporary buildings, can be gained from the 30 high-quality and well-chosen illustrations that adorn this beautifully produced book. They include a fine portrait of Henry by the court painter Richard Evans. It might be thought that, in this day and age, the provision of a German and an English text under one cover is a trifle de trop, although it certainly fits the opulent luxuriance of the subject matter.

• Tim Blanning is the Emeritus Professor of Modern European History at the University of Cambridge and a Fellow of Sidney Sussex College. He is also a Fellow of the British Academy