Next January, Tate Modern will hold the first major exhibition of the work of Pierre Bonnard in Britain for 20 years. Pierre Bonnard: The Colour of Memory is an opportunity, according to Matthew Gale, the exhibition’s curator, “to bring Pierre Bonnard to a new generation… but also to rethink his position in the history of art, as a 20th-century artist, and therefore think of him in a slightly different way from how he has been seen before”.

Bonnard’s place in Modern art has long been debated. Picasso delivered a particularly damning verdict on him. “That’s not painting, what he does,” he said, accusing him of producing “a potpourri of indecision” and concluding that “he’s not really a Modern painter”.

Picasso’s great rival Matisse held quite the opposite view of his great friend. After reading a withering magazine article by the Picasso acolyte Christian Zervos entitled “Pierre Bonnard: Is He a Great Painter?”, published soon after Bonnard’s death, Matisse scrawled on his copy: “Yes! I certify that Pierre Bonnard is a great painter today and assuredly in the future.”

That conclusion is not as certain as Matisse might have hoped, but the Tate Modern exhibition attempts more than any before it to squarely place Bonnard within the Modern era, ignoring his work from the 1890s when he was associated with the symbolist Nabis group, and focusing instead on the four decades after 1912 to Bonnard’s death in 1947.

“He was notoriously shy,” Gale says, “and that has led to this sense that he was a solitary figure. But one of the aspirations of our project is somewhat to insert him back into history, to see how he responded to the circumstances around him, to see how he responded particularly to the very traumatic experience of both the First and the Second World War, but also personal tragedies that underlie some of his activities.”

The notoriously shy artist photographed in 1941

Bonnard embraced many modern-world technologies: a keen photographer, he used some of his images to inform his paintings; and he owned a car as early as 1912, a Renault that he apparently painted yellow, Gale says. (“One cannot have too much yellow,” the artist once said.) The car “meant that he moved consistently around the country”, Gale explains. “He would spend the summers in the north in Normandy, and winter in the south.” Helen O’Malley, Gale’s co-curator, says: “There are great stories about how he would pin his canvases to the wall, and he would roll them up and shove them in the back of his car, and they would move house, drive to the next spot and the canvases would come out and be back up on the wall.”

Bonnard’s response to the First World War is little known. A Village in Ruins near Ham was painted in May 1917, as part of a system of taking artists to the front “to capture a sense of the destruction and the suffering of the armed forces”, Gale says. “You can see that Bonnard is trying to catch an instant vision mediated through his studio practice into what is a pretty unusual painting for him.” Alongside that work will be The 14th of July, capturing nocturnal Bastille Day celebrations in 1918, complete with a carousel in the background, and, Gale says, “a figure who looks a bit like Delacroix’s Liberty on the Barricades, surging up, giving a sense of the revival of peace and its return to France after the traumatic experience of the First World War”.

Gale insists that this is not to suggest that Bonnard should not be viewed as a war artist, “but to acknowledge that he has that awareness of what’s going on in the world around him and tries to bring that into his art in a way that has hitherto been rather overlooked”. In the Second World War, Bonnard, who was then in his 60s, was essentially trapped in his house at Le Cannet, above Cannes.

A Ruined Village Near Ham (1917) © Domaine public/CNAP/ photo: Yves Chenot

“His works in that period are primarily landscapes and yet he is pushing into abstraction in quite a heavy way,” O’Malley says, “and we think that is linked to the fact that it was a difficult time for everyone, so his work is becoming increasingly emotional and distorted.”

Gale adds: “We know from the exchanges that Matisse and Bonnard have in their letters that there are shortages of fuel, petrol, food, art supplies, and so just on the material front it’s very difficult. Matisse was very ill, Bonnard’s wife was very ill. In fact what’s slightly overlooked is that when she died, Bonnard then went into hospital for a period, and in 1943 one imagines hospitals are working quite hard.”

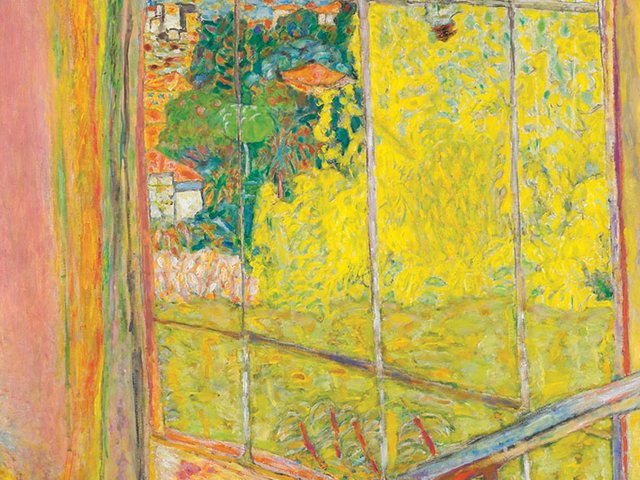

Around 100 works, including masterpieces lent from major international collections, will show the different subjects, tones and emotional registers Bonnard would achieve, from views of landscapes from interiors such as Dining Room in the Country (1913) and The Studio with Mimosas (1939-46), through to the seminal series of paintings featuring Bonnard’s wife, Marthe in the bath, to the troubling, brutal Self-Portrait (The Boxer) of 1931. Gale and O’Malley hope that the exhibition will change the too-easy assumption that associates Bonnard with that similar French word, bonheur, meaning happiness.

“It’s supposedly joyous,” Gale says, “but actually one of the things that we’ve been talking about a lot is that there’s a different emotional heft to these works, that isn’t simply: ‘Well, it’s lovely colour, therefore, let’s just revel in it.’ When you start looking at the detail of them, you can see that there are complicated things going on there and there’s quite a lot of complicated backstory, as well.”

Pierre Bonnard: The Colour of Memory opens at Tate Modern on 23 January 2019 and is supported by Mr & Mrs Chung Kiu Cheung. It will tour to the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek in Copenhagen and the Kunstforum, Vienna.