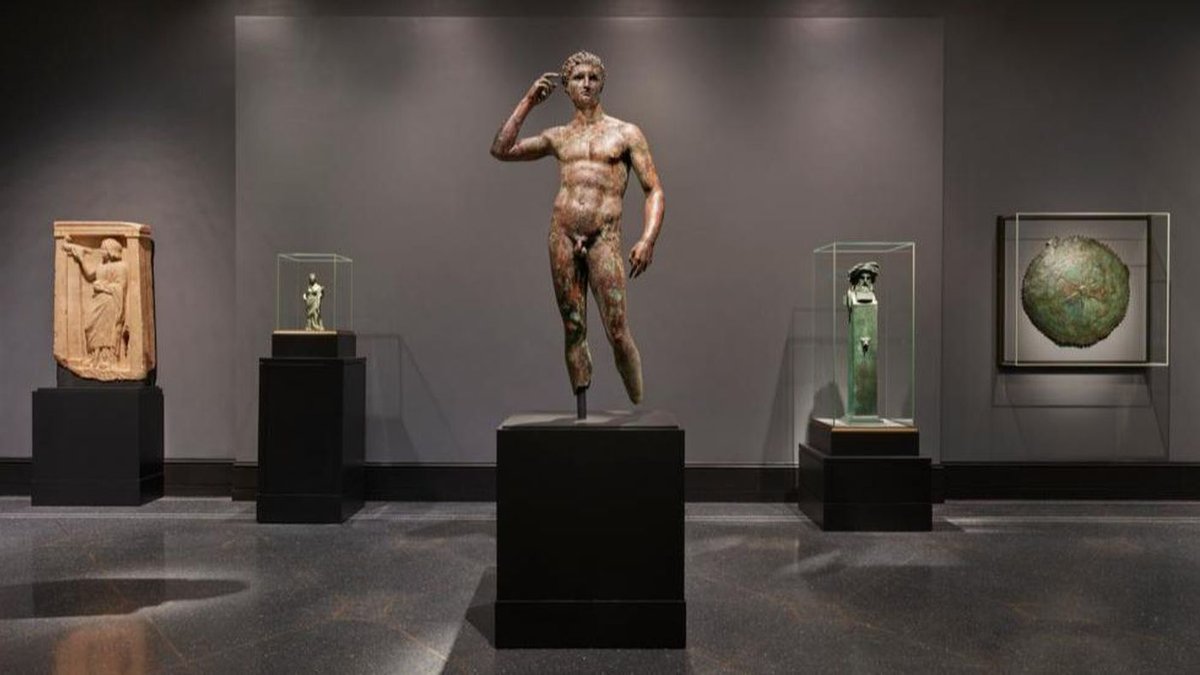

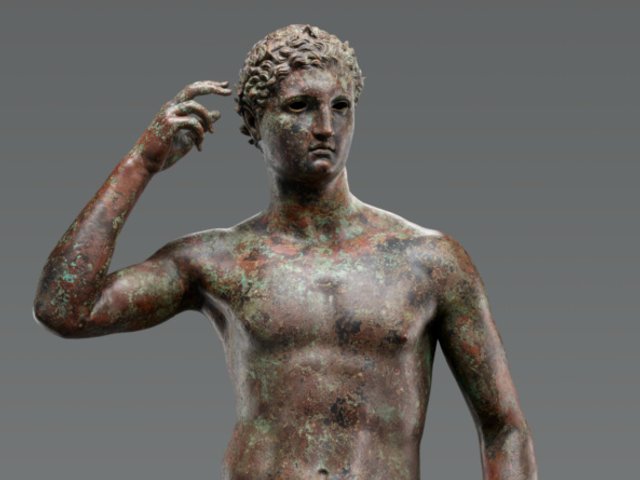

The J. Paul Getty Trust will appeal an Italian court’s order, issued on 8 June, directing it to turn over one of its key and long-contested antiquities: the Statue of a Victorious Youth, dating to the second or third century and one of the last remaining examples of ancient Greek bronze sculpture.

“We are disappointed in the ruling,” a Getty spokesman said in a statement, adding that since it was “found outside the territory of any modern state, and immersed in the sea for two millenniums, the Bronze has only a fleeting and incidental connection with Italy”. The statue was pulled out of the sea in 1964 by Italian fishermen, off the Adriatic coast near Fano. Both the Getty, and 50 years of prior decisions by Italian courts, have concluded that the work was not found in Italian waters.

The statue was likely removed from Greece by the Romans, and the ship carrying it probably sank at sea on its journey home. The sculpture, possibly a tribute to a real-life victory of a Greek athlete at Olympia, is one of few surviving life-size Greek bronzes, according to the Getty.

The fishermen sold the work and it was removed from the country, leading to a string of public battles for its return. Rome’s Court of Appeals ruled in 1970 that there was insufficient evidence that the bronze belonged to Italy or that it was of “artistic and archaeological interest”. In 1977, the Italian police reinvestigated the object's removal from Italy. That same year, the Getty bought the work for almost $4m and soon after placed it on public display in the Getty Villa in Malibu, California. In 1989, Italy made its first request to the Getty to return the sculpture.

In the June order, Judge Giacomo Gasparini of the Court of Pesaro said the Getty bronze must be forfeited because the work was disembarked into and exported from Italy illegally, and that its finder did not follow state procedures for declaring archaeological finds and exporting artistic works. These actions, he said, caused the work to become “part of the [Italian] state’s patrimony”.

Judge Gasparini also concluded that the bronze was found in Italian territorial waters, citing statements to police in 1977 that referred to a location a few miles off the coast where deep sea fishing nets are not used. The judge said that even if the waters were not Italian, the discovery was made by individuals aboard an Italian ship, using the ship’s fishing nets, which together represent state territory and make the statue subject to Italian cultural heritage laws.

The Getty disagrees, and not only about where the work was found. The bronze was in Italy only briefly, the Getty says, and any prosecutions in Italy of the individuals who sold the statue were dropped for lack of evidence.

After J. Paul Getty died in 1976, the Getty bought the work following an extensive review, it says, including a determination by German authorities that the work could be legally sold in Munich, the Italian culture ministry’s failure to join any of the legal proceedings about the bronze, a 1968 Italian high court ruling that there was no evidence the statue belonged to Italy, a statement by the Italian ministry official in charge of export licenses that Italy would not pursue any claim, and the Getty’s own analysis of the law and facts.

Patty Gerstenblith, a law professor at DePaul University, told The Art Newspaper that if the bronze “was found in Italian national waters, then Italy would be the owner and the statue would be stolen property under US law, as well as under Italian law”. Even so, she said, to get the statue, Italy would probably have to sue the Getty in US courts, where it would face legal statutes of limitations that it was too late to sue.