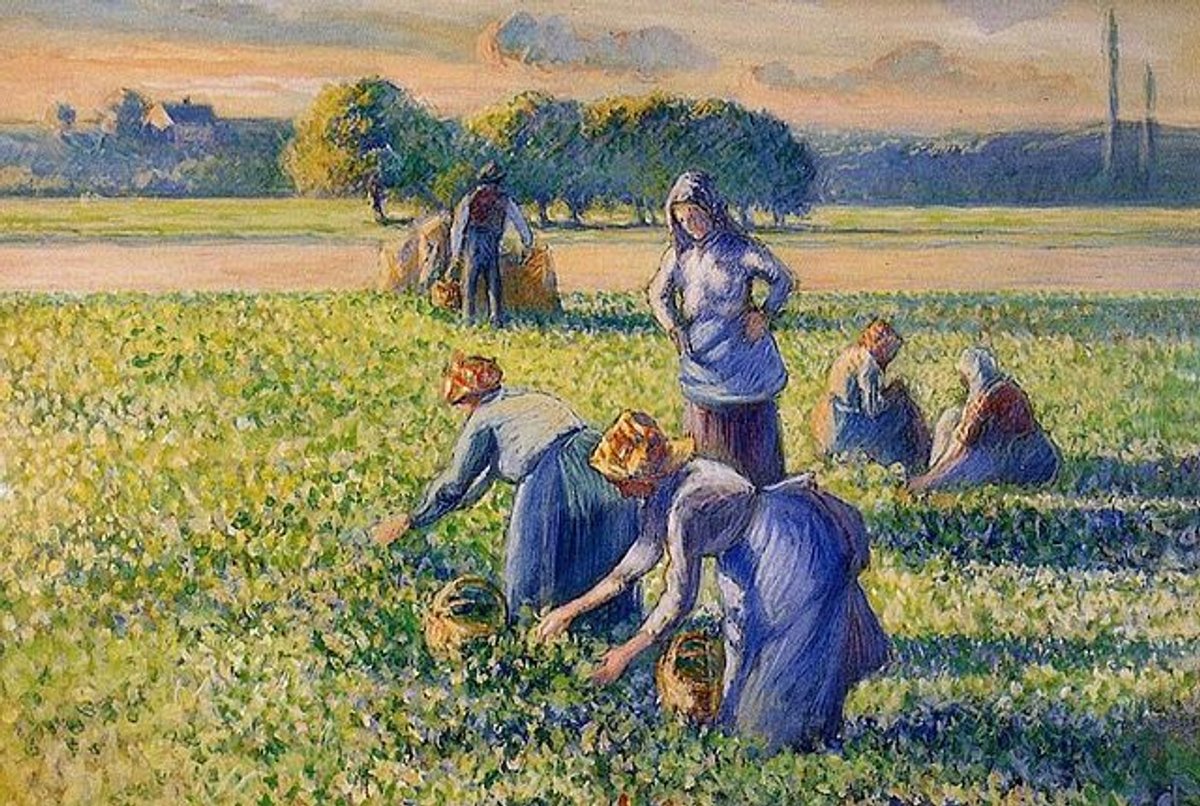

“I don’t understand why I’m here,” said Bruce Toll, the American collector of Impressionist art, in a Paris court on 6 June. The real estate entrepreneur was asking a court of appeal to give him back The Pea Harvest (1887), by Camille Pissarro, seized last year while on loan to an exhibition at the Musée Marmottan in Paris. Last November, a court decided to restitute it to the heirs of Simon Bauer, whose collection of 97 paintings was expropriated in Paris in 1943.

"I bought the painting in 1995 in good faith at Christie’s," Toll told the court. "It was sold by Sotheby’s 30 years earlier and before that, it had an export licence. In New York, as long as a work is sold in good faith, there is no recourse against the buyer. People will refuse to lend works of art to France."

The Bauer family has obtained this restitution on the basis of an order made by the French government on 21 April 1945. Article one of the law states that any seizures carried out during the German occupation is "considered null and void" and the "dispossessed owner must be returned his item" through an emergency procedure. All subsequent transactions are also considered void, with article four stating that "the buyer or subsequent buyers" are automatically "considered possessors in bad faith in regard to the owner".

“The order does not leave any margin for interpretation by the judge”, says the Bauers’ lawyer. “He can only record that the transactions are void and that the item must be returned to the victim. I can understand why Mr Toll has difficulty grasping legislation that is indeed exorbitant compared with common law. But it is an exceptional law, enacted in the unique historical circumstances of the Shoah and the racial laws in France."

On the basis of the 1945 order, French courts ordered the Louvre to restitute five Italian paintings in 2000, including a Tiepolo that has been since purchased by the J. Paul Getty Museum. But this is the first time it has been used against a private collector since the revival around 20 years ago of the debate over looted art.

All subsequent transactions are also considered void, article four stating that 'the buyer or subsequent buyers' are automatically 'considered possessors in bad faith in regard to the owner'

"This is absurd. It is impossible to condemn all good faith transactions for ever and ever,” said Toll’s lawyer, Ron Soffer, who wonders why the Bauers did not act when the painting was first sold in 1966 at Sotheby’s in London, then in 1995 at Christie’s in New York for $880,000. The painting had, in fact, been seized in 1965 in Paris, before being given back to an American dealer, David Findlay, who then transferred it to London, "at a time," says the Bauers’ lawyer, "when French justice was not sensitive to the matter of looted art."

Simon Bauer’s heirs have recently received an indemnity of €109,000 (a calculation based on post-war values) from the French government, but they have promised to return the money. Their lawyer, Cédric Fischer, asked why Toll is not suing Christie’s, which "had all the elements for the provenance". Soffer replied that the contract signed by the buyer stated a limitation, now long past, and established the competence for any litigation in New York.

Christie’s, which is not party to the proceedings, says that it "awaits the outcome, which will raise many important Holocaust issues for the French market". The decision of the court of appeal is expected on 2 October but will certainly lead to a recourse to the High Court of Justice.

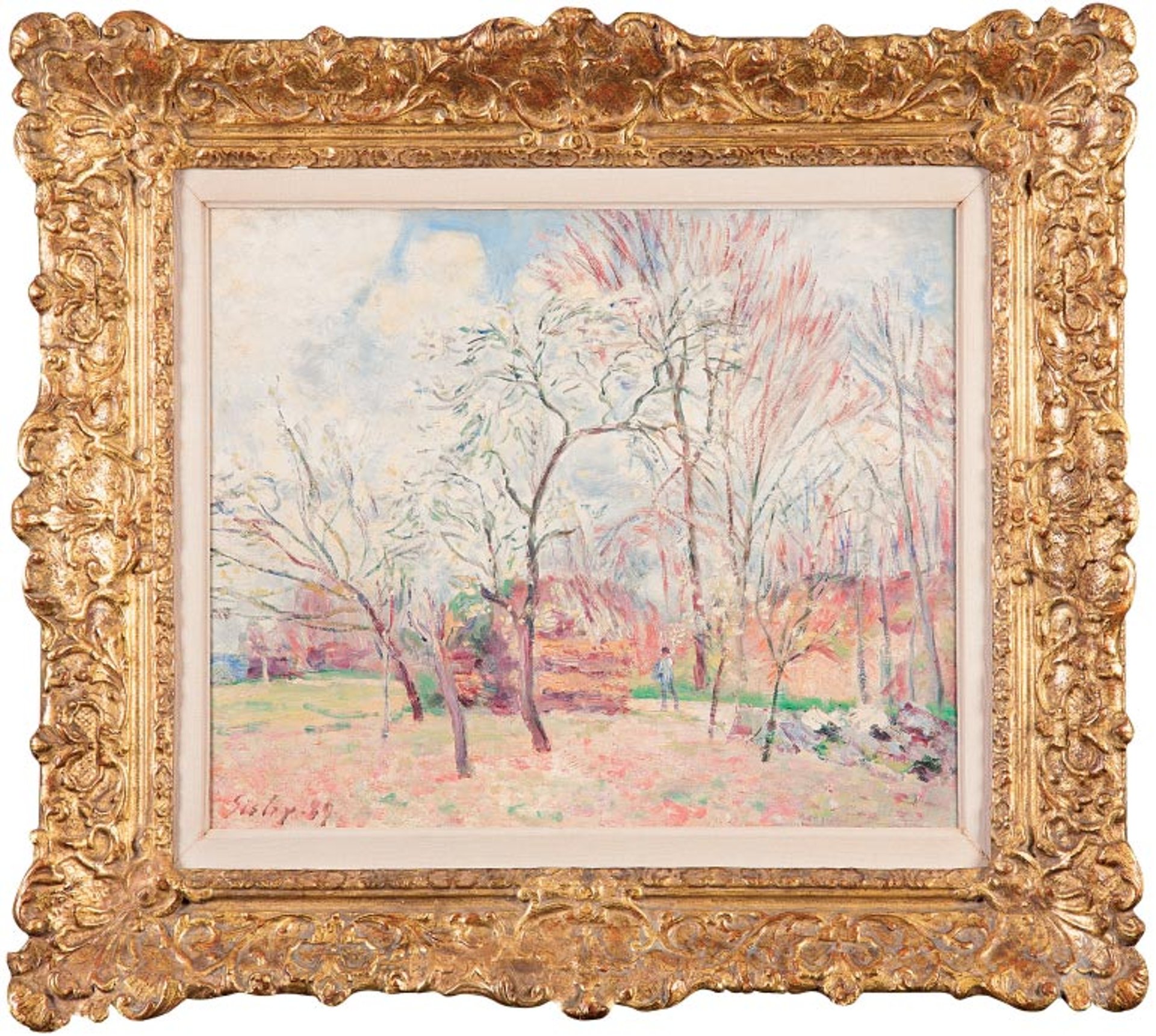

First Day of Spring in Moret (1889) by Alfred Sisley Galerie Dreyfus

Christie’s has also been accused of failing to use due diligence when it sold First Day of Spring in Moret (1889) by Alfred Sisley for $333,500 ten years ago. The French newspaper Le Monde has revealed that this painting has been seized from Galerie Dreyfus in Basel, Switzerland, after a criminal complaint in Paris filed by the heirs of Alfred Lindon, whose collection of Impressionists was stolen by Reichsmarschall Goering from a safe in Chase Bank in 1940 in Paris. The complaint was filed in August 2016 when the British branch of the family was alerted by a Canadian company, Mondex, which researches looted art.

Alain Dreyfus told The Art Newspaper that he is prepared to "give the painting back to the family, as soon as Christie’s reimburses me. When I buy at an auction house, I place my trust in it. Obviously, they did not do their research; the provenance was very dubious," he said, pointing out that the sale catalogue was hazy about the ownership between 1935 and 1972.

Dreyfus says that, after having struggled for more than a year and a half with the auction house, he sent it an invoice for the full price plus 80% interest. Christie’s has replied that "all the known provenances and accessible history were extensively researched and referenced a decade ago. It is only thanks to a digitised data bank that new information became available in 2010". Christie’s spokesperson Catherine Manson adds that although the auction house "is not involved in this legal proceeding, it would be more than happy to encourage a dialogue and facilitate a solution".

Antoine Comte, the Lindons’ lawyer, says the case is deeply embarrassing for Christie's. “The painting is listed in the French register of looted art as belonging to this family. All they had to do was to call the Lindons, who have a photo of their parent standing in front of the painting."