The New York School produced three important critics from the generational cohort of Abstract Expressionism’s principle artists: they were Clement Greenberg, Harold Rosenberg and Thomas B. Hess, who was also the chief editor of Artnews when that magazine was the primary forum for sophisticated debate about emerging tendencies in art. There was only one historian of modern and contemporary art of the same cohort who had a comparable impact on how the public viewed this first internationally significant school of art from the US and all that followed: he was Irving Sandler who died 2 June at the age of 92.

In many respects, Sandler was an unlikely candidate to become a major champion of advanced painting and sculpture, until one recalls that most of the men and women who made the work about which he wrote — Jackson Pollock, Lee Krasner, Willem and Elaine de Kooning, Mark Rothko, Franz Kline, Philip Guston, and Arshile Gorky — were also born outside the magic circles of high culture in the period between the two world wars. Like a large proportion of them, Sandler was a child of Eastern European Jewish immigration. His father was a passionate and peripatetic advocate of Socialism, who took his family from Brooklyn, where his son was born, to Winnipeg, Canada and from there to Philadelphia where the young Sandler was a “newsy” selling The Daily Worker on the streets. At 17 he joined the Marine Corps, served for the last three years of the Second World War and was honourably discharged with an officer’s rank. Late in life he sketched a memoir that was to be called From Red Diaper Baby to Semper Fi (the Marines’ motto) savouring all the ironies of the contradictions inherent in his all-American immigrant’s trajectory.

Following his demobilisation, Sandler attended Temple University, in Philadelphia, receiving his bachelor’s degree in 1948, and followed that up with a Master’s degree in American Studies from the University of Pennsylvania in 1950. Later, he did graduate work at Columbia University in New York and earned a doctorate in art history in 1976 from New York University. All of this laid the ground work for a teaching career mostlg spent at the State University of New York at Purchase, where he also advised the curatorial programme at the Neuberger Museum which opened in 1974.

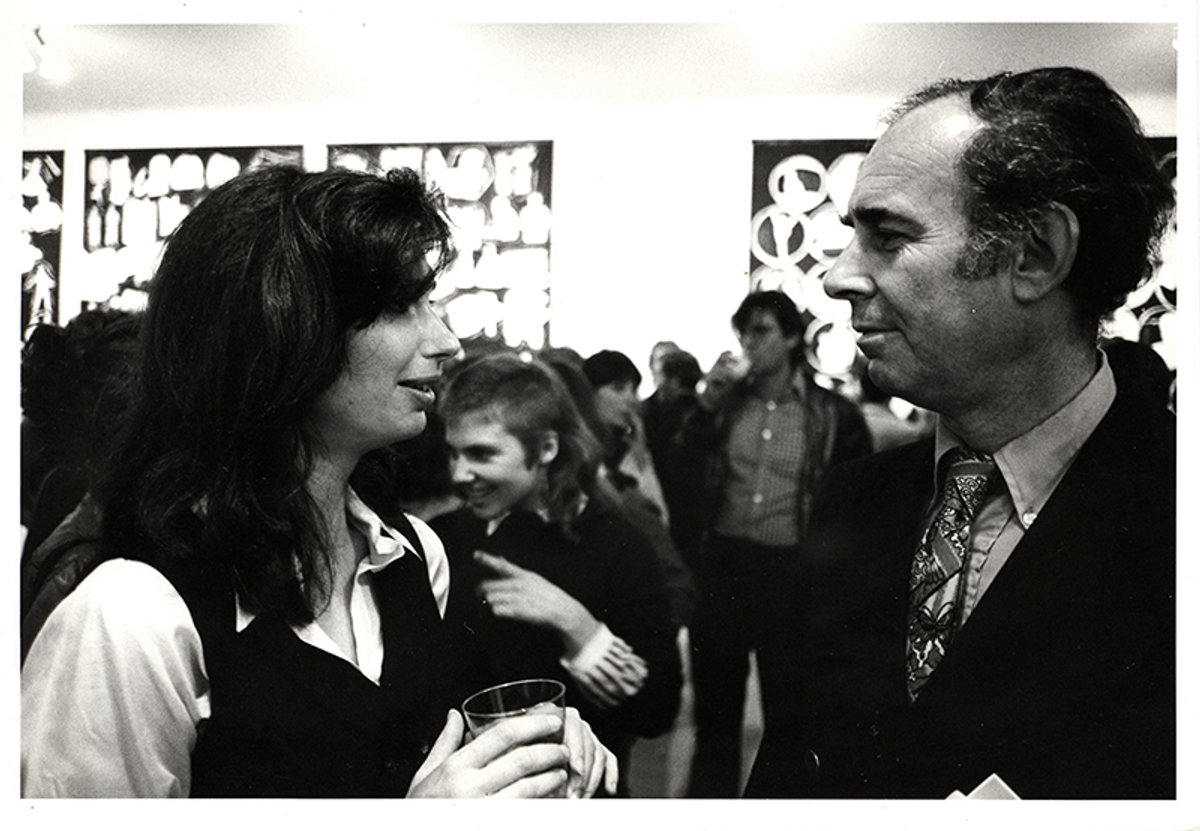

This formal academic training noted, Sandler’s real “universities,” (to paraphrase Maxim Gorky’s use of the term in his memoir of his school-of-hard-knocks education), were mostly the lofts, studios, bars, clubs, panel discussions and downtown galleries of the burgeoning postwar New York art scene. In that context, Sandler mingled easily with his creative, often contentious contemporaries using his unflappable good nature, tolerance for and keen appreciation of sharply differing aesthetics, and an avid journalist’s and historian’s knack for taking down the words he heard, describing the art he saw and characterising the artists and supporting cast of critics, dealers, collectors and curators then in formation. It is no exaggeration to say that Sandler knew them all, and though underestimated by some of his peers because of his affable avidity, virtually all who knew him liked him and came around to respecting him.

More than any of his coevals, Sandler was keenly interested in and involved with what came after Abstract Expressionism. First off that meant three artists closely associated with the co-operative Tanager gallery, where he did his apprenticeship sitting in the Gallery during exhibitions and tidying up at the end of the day, a role that earned him the moniker “The Sweeper Up After Artists” from the poet, Museum of Modern Art curator and fellow Artnews contributor Frank O’Hara. He wore the ironic nickname with mirth and pride. The trio in question consisted of the painterly realist Alex Katz, the Hard Edge abstractionist Al Held, and the strict “eye ball” realist, Philip Pearlstein. (Katz in 1948 limned a wedding portrait of Sandler and his wife Lucy Freeman Sandler, professor emerita at New York University and a much celebrated expert on medieval manuscript illumination, who survives him as does their daughter Cathy, a graphic, a designer.)

Add to the list of artists close to him the sculptors George Sugarman, Louise Bourgeois, proto-Minimalist painter and sculptor Ronald Bladen, painters Joan Mitchell, George Ortman, and Ad Reinhardt, and you have a partial inventory of the artists whose works filled every inch of the Sandlers’ two successive apartments in modern high rises near Washington Square, where art historians, museum curators and directors, artists, poets — ranging from notables of the New York School such as Bill Berkson and Bob Holman to neighbour Yvgeny Yevtushenko — and critics regularly gathered. These gatherings were in some respect an informal version of the sessions held at the famous Artists’ Club of the 1950s whose evenings Sandler sometimes planned and frequently participated in, whether from the stage or from the floor. No one in New York attended more panels nor more scrupulously recorded the proceedings which resulted in an invaluable archive now at the Getty Research Institute.

Some of the treasures on the Sandler’s walls and floors — all destined for museums including Katz’s wedding picture which will go to the National Gallery in Washington DC — were gifts from the artists in the days when art did not equal money. One in particular, a rare, small square “black painting” by Reinhardt was a purchase and, in that case, money was an issue. When Sandler asked the famously prickly painter how much it would cost, Reinhardt promptly answered: “Well, Irving, what would hurt?” To which Sandler replied $300, then a sizeable sum in downtown circles, and instantly that became the price.

True to his activist upbringing and his early affiliations with do-it-ourselves galleries, Sandler was a leading light in any number of campaigns to protect free speech of all kinds, to develop alternative spaces for artists to make and show their work. A co-founder with Trudie Grace of Artist’s Space in 1972, where the “Pictures Generation” made their debut a few years later — making Sandler one of the very few “older timers” of the New York School to consistently advocate for work by artists who came after them — to foster open debate of art ideas during the conservative culture wars of the 1980s and 1990s and, until his death, to press for expanding horizons at moments when they seemed to be contracting in every sector except the market. In his last decades, his indefatigable efforts included chairing ad hoc committees and steering private foundations, and pushing the National Endowment for the Arts to fund grants to artists in the form of cash or work spaces.

Sandler’s art historical legacy, large and avowedly pluralist, is contained in a long list of articles written for publications ranging from the New York Post – like Reinhardt’s cartoons for the daily P.M. in the late 1940s Sandler’s columns didn’t talk down to the “common man and woman” but rather directly to them – to the house organ of Abstract Expressionism Artnews to the leading art glossy of the 1960s to today, Artforum, to countless catalogues and occasional essays. His major books, which constitute a continuous, lucid, lively, and nuanced analytical narrative of the history of the visual arts as they unfolded in his time and place are The Triumph of American Painting: A History of Abstract Expressionism (1970) – the chauvinist title was not Sandler’s own but something imposed on him by the publisher - The New York School: Painters and Sculptors of the Fifties (1978,) American Art of the 1960s (1988) and The Art of the Postmodern Era: From the Late 1960s to the Early 1990s (1996.)

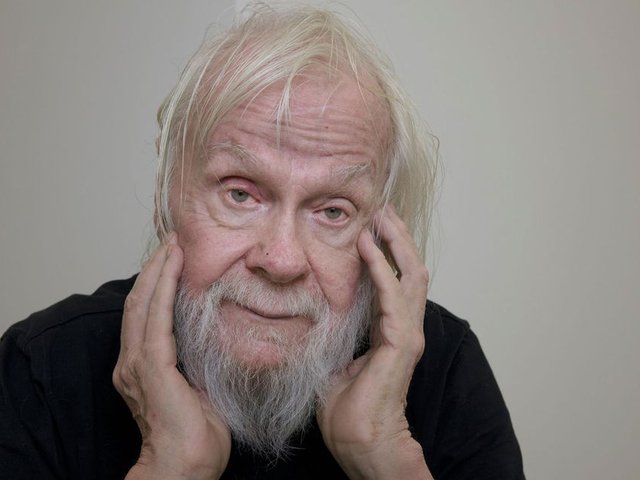

The bemused avuncular optimism and enthusiasm that gained Sandler access to history-in-the-making never deserted him. After listening to a good argument or seeing a dozen or more shows over a two-day weekend he would, while in his 80s when many others of his generation and far younger had soured on the vanity and cupidity of the increasingly hyped increasingly commercial “post-modern” scene, he would spontaneously declare “I love my art world.” Much of it loved him back. Certainly all of it owed him a debt.