Shortly after the publication last October of two exposés detailing decades of sexual abuse and assault by the US film producer Harvey Weinstein, the #MeToo movement hit the art world. As accusations continue to unfold, US museums have been forced to confront, publicly and in real time, ethical dilemmas such as how or whether to show work by alleged abusers—but there is no standard, accepted institutional response to such situations.

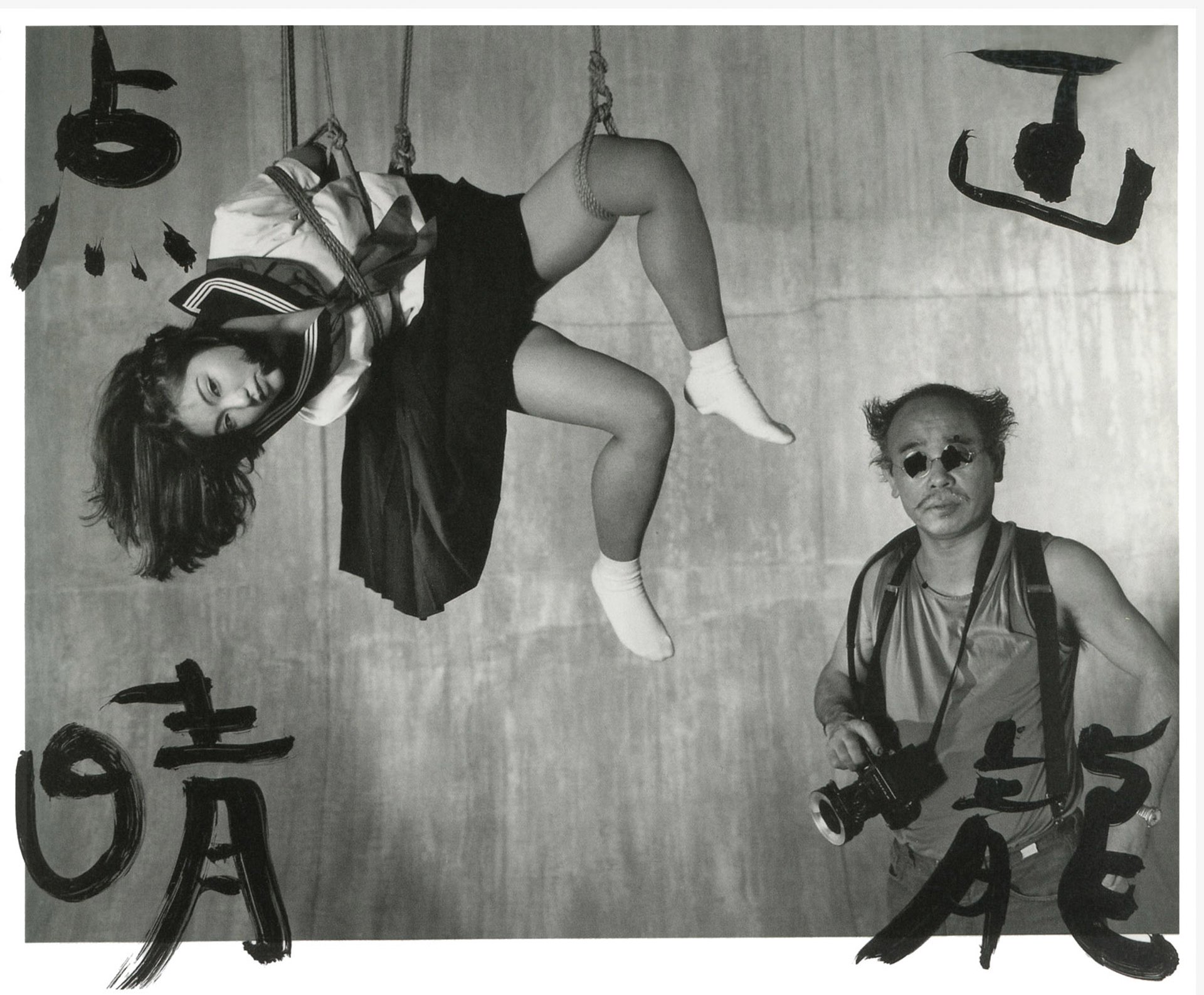

“The worst thing a museum can do is plug its ears and hope it’ll go away,” says Maggie Mustard, who co-organised The Incomplete Araki: Sex, Life and Death in the Works of Nobuyoshi Araki at the Museum of Sex in New York (until 31 August), a solo show on the Japanese photographer, whose explicit works often depict women in bondage.

Months into preparation for the show, the curatorial team learned of an allegation of sexual misconduct against Araki by a former model. Mustard (who is not on the museum’s staff) contacted the woman and incorporated her accusation into the exhibition’s wall text.

Nobuyoshi Araki’s Marvelous Tales of Black Ink (Bokuju Kitan) 068 (2007) Courtesy of Private Collection/Museum of Sex New York

Several months later, one of Araki’s longtime muses, Kaori, got in touch; the photographer had emotionally bullied her for over a decade, she said. The organisers decided to add her story to the show after she went public in a blog post, and installed an interactive tablet with Kaori’s full post in Japanese and English in the gallery in May.

They also added new wall text explaining the recent curatorial decisions—Mustard says that the public should know about these conversations.

Some museums have scrapped or removed exhibitions by artists accused of harassment or abuse—with their support. When allegations of sexual harassment against the photographer Nicholas Nixon surfaced during his solo exhibition at the Institute of Contemporary Art (ICA) Boston, the museum initially added signage and created an open online forum, despite calls for the exhibition to be closed. But in April—at Nixon’s request—the ICA chose to end the show ten days early. (When contacted by The Art Newspaper, the ICA said only that “museum leadership” made the decision.)

In January, the National Gallery of Art (NGA) in Washington, DC decided to postpone planned solo shows of the artist Chuck Close, accused of sexual harassment, and the photographer Thomas Roma, accused of sexual misconduct, after consulting with them. Close and Roma both concurred that “it is not the right time to present these installations”, says an NGA spokeswoman. There is currently no timeline for staging the shows. However, the museum has kept a major Close painting on view in its permanent collection galleries, she says.

The Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts (Pafa) in Philadelphia continued its show of Close’s photographs that were on view when allegations against him came out last December. After holding a community forum, they added an interactive pop-up exhibition and “project space” focused on issues of gender and power. Cancelling the show “would allow everybody to kind of put their hands together and say, ‘We did this; we got the show closed’”, says the museum’s director, Brooke Davis Anderson. “I felt that the conversation was more important than having a sense of victory.”

Anderson, Mustard and Kenneth Weine, the chief communications officer of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, agree that there is no “one-size-fits-all” solution to these issues. For example, the Met contacted the artist Jaishri Abichandani ahead of the silent #MeToo protest she organised at the Met Breuer, New York, last December, during its solo exhibition of work by her alleged abuser, the late Indian photographer, Raghubir Singh. The museum gave Abichandani relevant information about security concerns, such as poster size, and contacts for the security and communications teams.

“Listening deeply and showing empathy and being transparent are the steps we need to be taking,” Anderson says. “Understanding [that] you don’t know everything and you don’t have all the answers—and then coming up with a strategy that you hope takes all of that in.”