The hunt for Frida Kahlo’s long-lost painting La Mesa Herida (the wounded table, 1940) has been revived in Mexico, where a researcher says he expects to track it down within five years. The work, a holy grail for Kahlo scholars, went missing after the artist donated it to the former Soviet Union. Last seen in an exhibition in Warsaw in 1955, it disappeared on its way to Moscow.

For decades, art historians have scoured archives, customs offices and museums in the Americas and Europe in search of the painting. But Raúl Cano Monroy, an investigator who organised an exhibition at Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo’s Home-Study Museum in Mexico City last year, says he has uncovered new clues after working with the archive of the National Front of Plastic Arts, which promoted Mexican art abroad during the 1950s.

“I think in five years my investigation will bear fruit,” Cano told the Mexico newspaper Milenio, adding that he has found an adviser to help in his research. When contacted by The Art Newspaper, Cano declined to reveal any further details about the evidence he has uncovered. “Given the circumstances, and that I can’t share the information that I have on the topic, I can’t say anything,” he says.

However, his optimism has been enough to renew excitement in the decades-old mystery. “It would be very good news,” says Carlos Phillips, a member of the Diego Rivera-Frida Kahlo Trust, about Cano’s promise. “We would appreciate anyone who can find it.”

Kahlo has become one of Mexico's most recognisable and best-loved artists, not only because of her signature style and unibrow, but because of the enigmatic symbolism in her work. A growing interest in her art has led both to fights over her image, and many popular exhibitions, including a recently launched digital deep dive on Google's Arts and Culture platform.

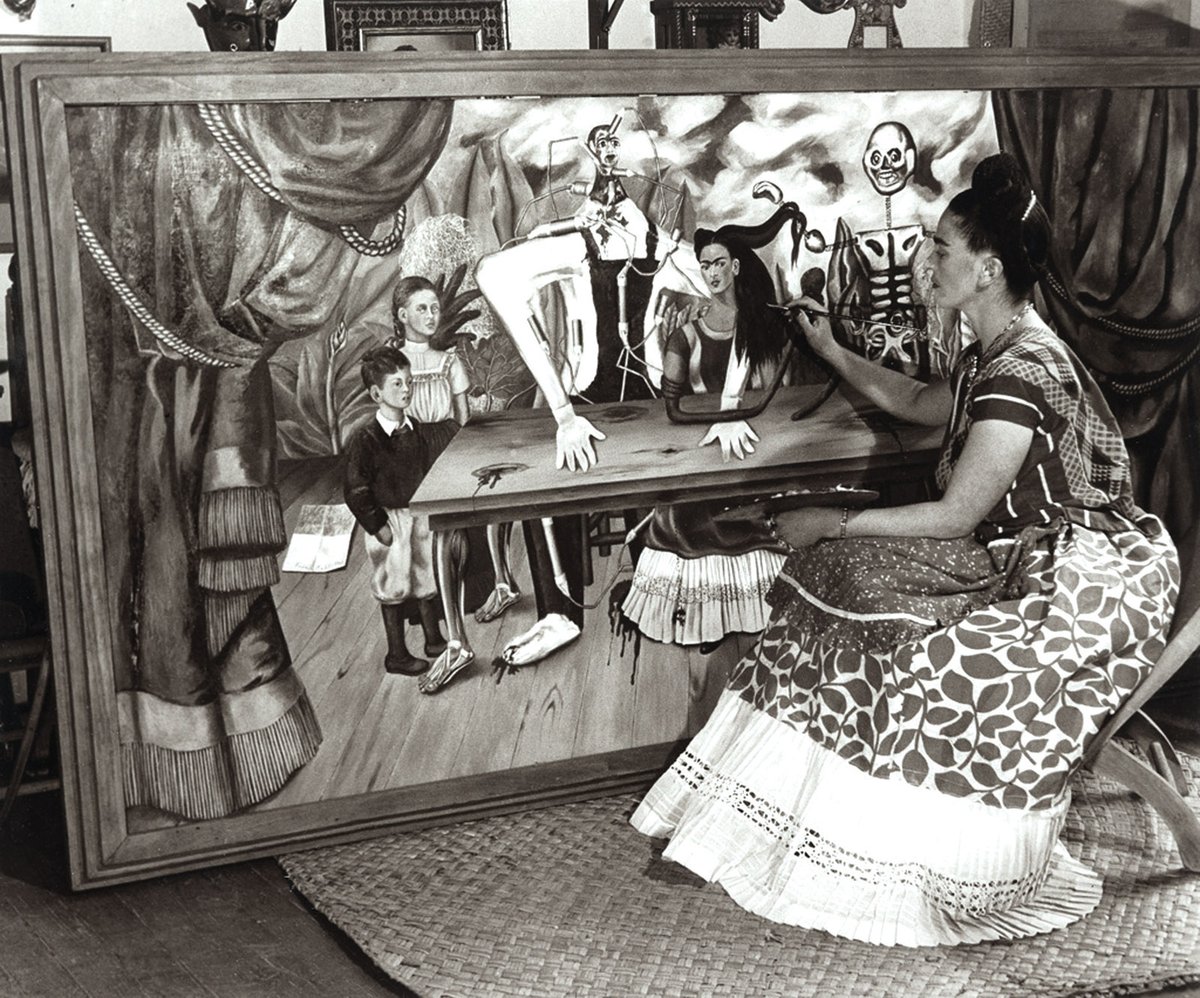

La Mesa Herida is Kahlo’s largest painting, measuring around 1.2m by 2.4m, and was done in oil on wood rather than on canvas. The work is a surreal depiction of Kahlo and guests—including a skeleton that plays with her hair, a Pre-Columbian clay figure that lends a limb to the seemingly armless artist, a grotesque figure believed to represent her womanising husband Diego Rivera, and her beloved niece and nephew—gathered around a table covered in bleeding vulva-like sores with flayed human legs. The work has been valued at more than $20m today.

“It’s important because it’s not only a self-portrait, it’s a statement,” says Helga Prignitz-Poda, a curator and art historian who is working on an updated catalogue of Kahlo’s art. She also organised an exhibition in Warsaw last year with the aim of raising awareness about the missing work.

Prignitz-Poda and the independent curator Katarina Lopatkina outlined their findings about the painting’s history in a recent essay for the International Foundation for Art Research (Ifar) Journal. The authors say that, although Kahlo, a dedicated Communist, sent the work to Moscow as “a gift of friendship”, documents show that Soviet officials considered it to be an example of “decadent bourgeois formalist art” and unsuitable for public display.

In 1954, the same year Kahlo died, Rivera requested that the painting be shown in Poland in an exhibition with other works by Mexican artists. The show at Warsaw’s Zacheta National Gallery of Art proved so popular that it was sent on tour to other countries in the Soviet Union and even made it to China. However, “there was no trace” of La Mesa Herida after the Warsaw leg, Prignitz- Poda says. “It’s as if it disappeared into thin air. The astonishing thing is that it’s the biggest and the heaviest [painting by Kahlo], so it’s really mysterious how it could disappear.”

Correction: This article was updated on 4 June to include Katarina Lopatkina, the co-author of the article Frida Kahlo's Lost Painting, The Wounded Table—A Mystery.