A week after Arco Lisboa came to a close in Lisbon, and hot on the heels of an influx of new galleries opening in the Portuguese capital, 130km east in the walled city of Évora, in the Alentejo region, some of Africa’s best contemporary artists have gone on show this weekend for the inaugural Evora Africa festival (until 25 August). While Lisbon and Porto are garnering the headlines as hotspots for artists and galleries, the Unesco World Heritage city seems a world away.

The “idea of decentralisation” away from the major cities is important, says the festival’s founder and director, Alexandra de Cadaval. The festival, which takes place at the Palácio Cadaval—which has been in the director’s family for 600 years—includes a performance and music programme running alongside the main exhibition, African Passions.

Visitors view one of Chéri Samba's paintings in the exhibition African Passions African Passions, Palacio Cadaval, 2018

The show of 16 contemporary African artists, shown together in Portugal for the first time, is curated by André Magnin and Philippe Boutté. Magnin made his name through establishing and directing the Pigozzi Collection—focusing on contemporary art from Sub-Saharan Africa—and now, with Boutté, runs the Magnin-a gallery in Paris.

During a press view, Magnin described how the Congolese artist Chéri Samba, standing beside him, “[before] painted for the Congolese people, now it’s for a global [audience]”. The remark mirrors the way many of the artists in the show—most of which Magnin met during extensive travels across the continent from the late 1980s onwards—have now become internationally known and collected.

Almost all the artists in the exhibition still live and work in Sub-Saharan Africa and many had trouble travelling to Europe for the opening weekend. It is “more and more difficult to get visas [nowadays]”, Boutté says. While importing works to Europe is relatively easy, it has become increasingly more complicated for the artists to travel, especially after the “migrant crisis”, Boutte says. Cadaval echoes Boutté, saying there were several “visa issues”, especially with the Congolese artist JP Mika and performers from Burkina Faso.

JP Mika, wearing one of his colourful patterned suits, alongside André Magnin African Passions, Palacio Cadaval, 2018

Mika made it in the end, and his colourful portraits of dancing and movement on patterned canvas—inspired by the La Sape dandy subculture—were complemented by his equally exuberant suits. Also in attendance, in her traditional Ndebele dress, was the octogenarian South African artist Esther Mahlangu, who has painted a specially commissioned mural in the palace’s courtyard as well as an old motorbike in her distinctive abstract patterns.

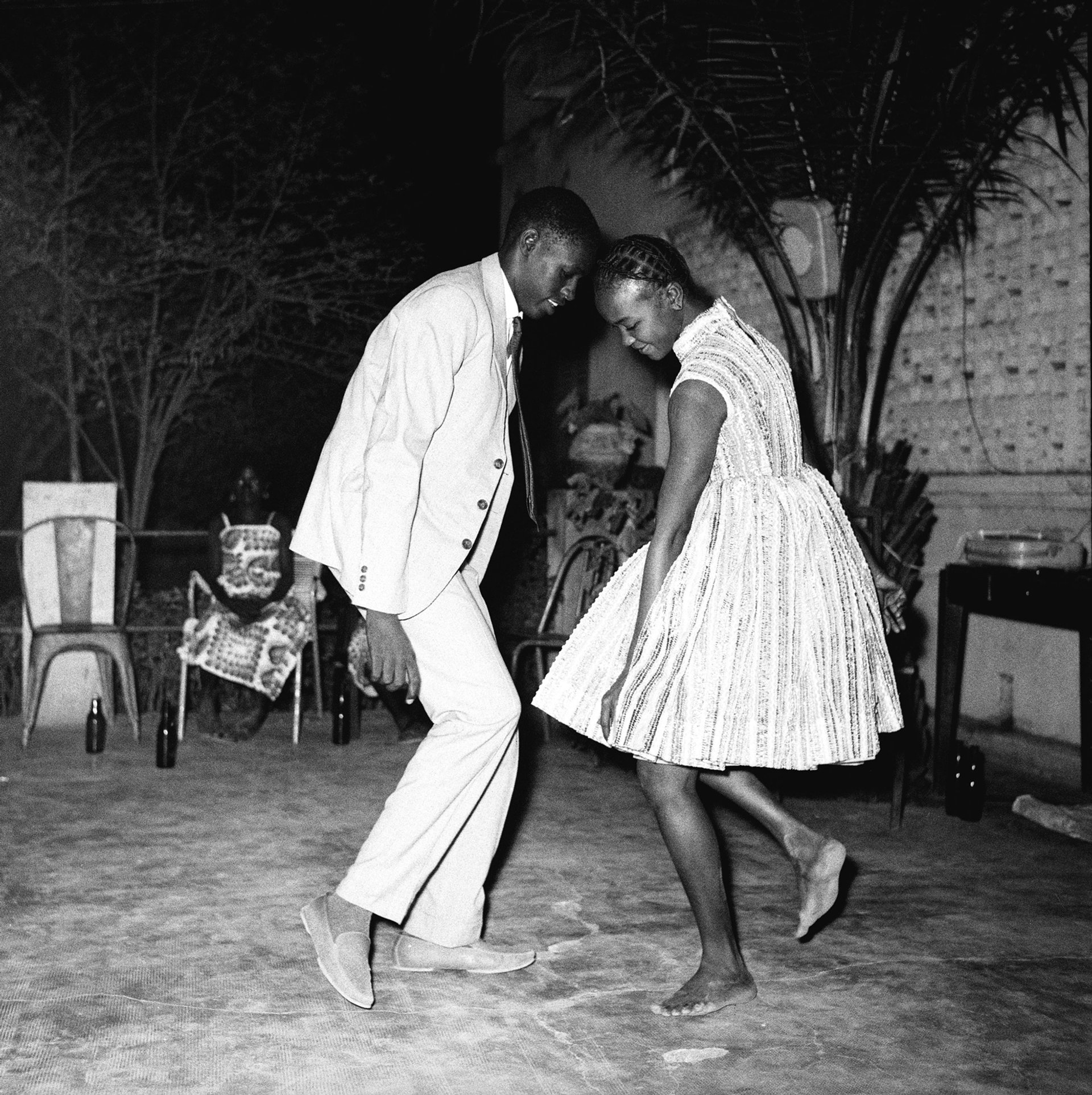

Malick Sidibé's Nuit de Noël (Happy Club) (1963) Courtesy of Magnin-a gallery, Paris

Works by the Malian photographer Malick Sidibé—one of the “best in Africa”, Magnin says—are one of the highlights of the exhibition. “They are full of love, full of happiness”, Magnin says, pointing to Sidibé’s photograph of a brother and sister dancing in Nuit de Noël (Happy Club) (1963). The subjects of Sidibé's pictures, taken in Bamako in the 1960s, were not so different to us, dressed in Western clothes and listening to “the same music as us”, Magnin adds. Boutté printed many of the Sidibé photographs in existence and the ones on show were all done before Sidibé died in 2016, he says. The negatives are now with Boutté and Magnin, awaiting instruction from Sidibé’s heirs, Boutté says. But any decision is complicated by the fact that the photographer was survived by three wives and 17 children, he adds.

Although many of the editions of Omar Victor Diop’s best-known series, Diaspora (2014), have been sold, the whole lot have been reprinted just for the exhibition (and will be destroyed at the end), Magnin says. The self-portraits were inspired by Baroque paintings, football, and are named after notable Africans described in Western history.

The Yoruba artist Romuald Hazoumé, who lives and works in Porto Novo, Benin, has an installation made from his trademark jerry cans, titled Osa Nla (2015), installed in the palace’s 15th-century church. At the unveiling, the artist repeated a sentiment he has made before: that by using discarded materials in his work and then exhibiting and selling them in the West, he is returning the waste to where it came from. Hazoumé is due to have a show next year at Gagosian Gallery in New York, according to Magnin.

Untitled (2015) by Mauro Pinto Courtesy of Magnin-a gallery, Paris

It is the first time many of the artists have been shown in Portugal and both Boutté and Cadaval acknowledge it was important, although not essential, to include artists from Portuguese-speaking African countries, such as Filipe Branquinho and Mauro Pinto, both from Mozambique.

Cadaval lived for seven years in Mozambique, working with NGOs across the continent on humanitarian projects and “safeguarding traditional heritage”, she says. One of the elements Cadaval wanted to share with this festival was the “joie de vivre” she encountered even in the “hardest places”, she says. And after meeting Magnin, she realised he “manages to transmit that” through the artists he works with. “[In Africa] art and music go together [so] it made sense to go hand-in-hand [for the festival]”, she adds.

Cadaval hopes the festival, co-financed by the European Union’s Portugal 2020 fund and private sponsorship, will become a biennial and perhaps even travel to India, where she has worked in the past.