Adrian Piper’s retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art, A Synthesis of Intuitions, 1965-2016 (until 22 July), is also an analysis of artistic, academic and social institutions. A conceptual artist, Kantian philosopher and yogi, the New York-born, Berlin-based Piper has sought to transcend the boundaries between art and public discourse. Race is central to her investigations. As a light-skinned person of mixed African-American and white ancestry, Piper mobilises her own body and experiences as a social catalyst. In so doing, she has explored identity not as a fixed category but as a process.

The vast exhibition of nearly 300 works—which spans MoMA’s sixth floor and second-floor atrium—opens with unexpected juvenilia. Stepping inside the galleries, the viewer confronts a wall hung salon-style with faceted, psychedelic portraits that Piper made as a teenager, exploring the perceptual effects of LSD. As a student at the School of Visual Arts, Piper dropped figuration for abstract, permutation-driven conceptualism, befriending artists like Sol LeWitt and becoming a wunderkind by her early 20s. Several densely filled galleries reflect her prolific production from this era.

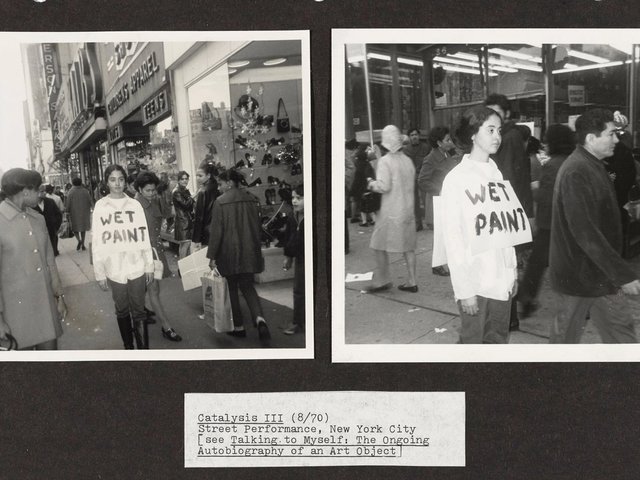

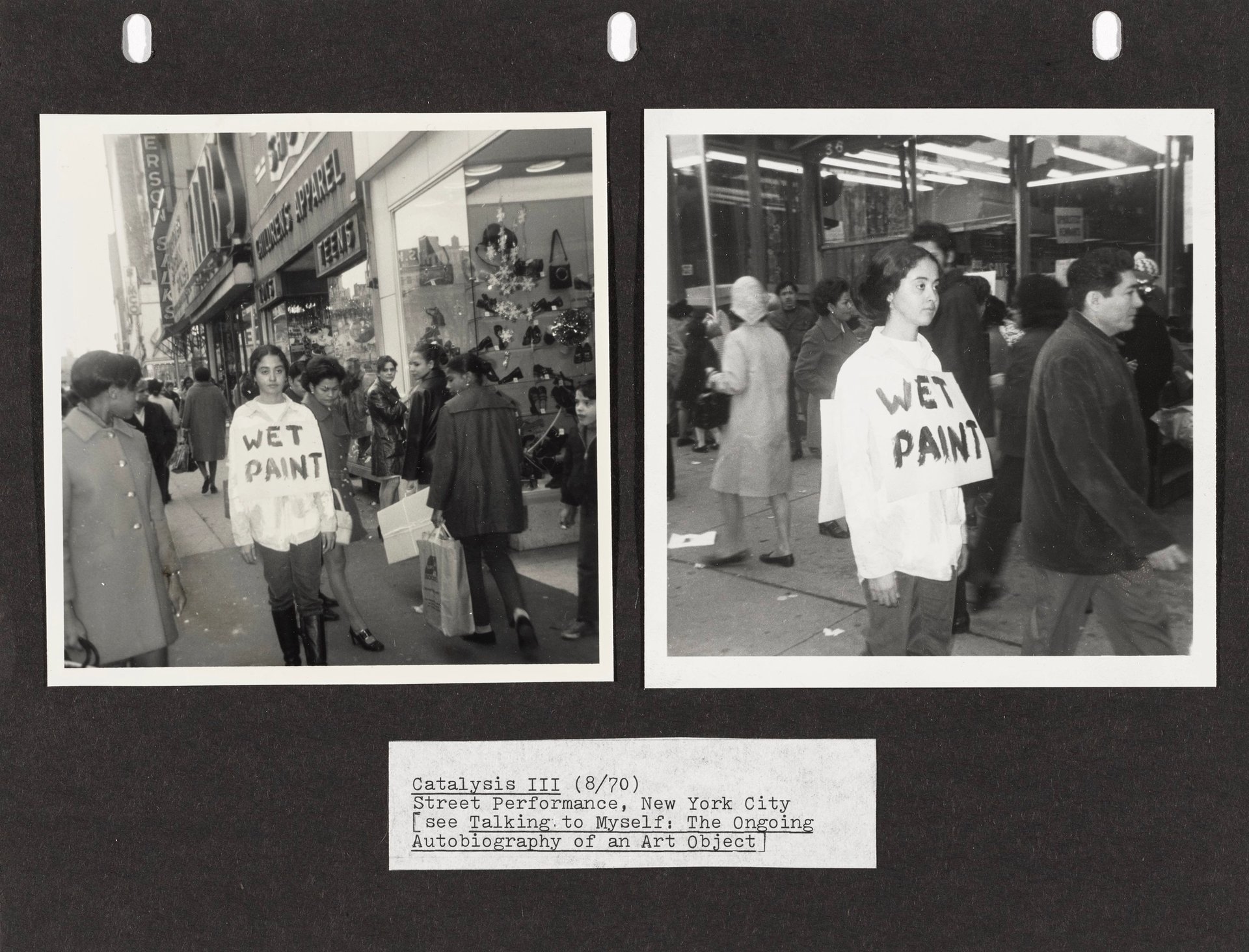

By 1970, Piper was motivated by protest politics to take her work to the streets. In her Catalysis series, she altered her appearance as a social experiment, by donning a Wet Paint sign at a department store, for example.

Adrian Piper, Catalysis III (1970) Adrian Piper Research Archive Foundation Berlin

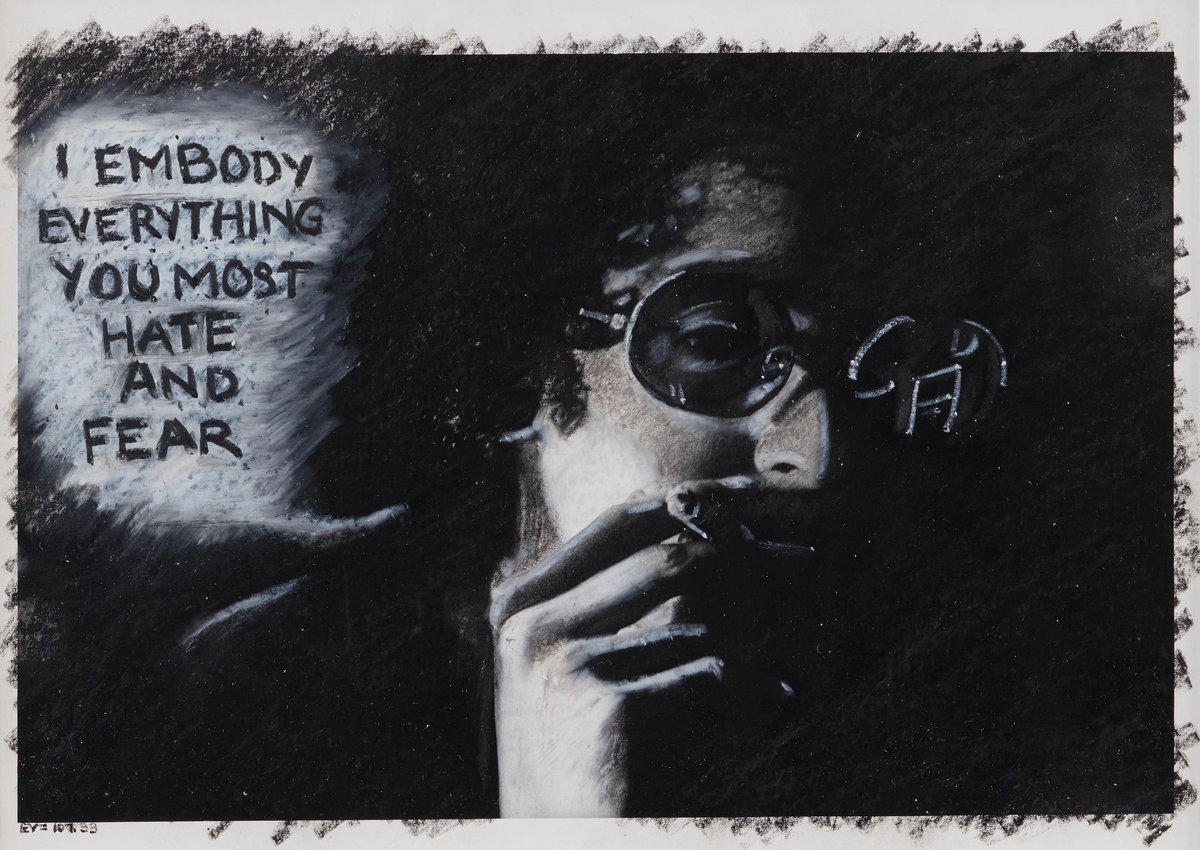

As she completed her undergraduate philosophy studies and started a PhD at Harvard, she performed in public as a male alter-ego called the Mythic Being. Clad in an Afro wig and sunglasses, this persona recited passages from Piper’s journal as ‘mantras’ and appeared in tiny Village Voice ads. Piper retired the character in 1975, but the experience of performing as a black man would affect her production to come. In a work from that final year, the Mythic Being is pictured smoking, with a speech bubble emanating like puffs from his cigarette: “I embody everything you most hate and fear.”

In an age of mail-order DNA tests and cultural discussion about microaggressions, Piper’s works from the 1980s appear exceptionally fresh. She created the multiple My Calling (Card) #1 (1986-1990), to discreetly announce her identity in polite situations like cocktail parties. “Dear Friend, I am black,” it begins. “I am sure you did not realize this when you made/laughed at/agreed with that racist remark.” These cards—as well as ones asking the recipient not to sexually harass the card holder—are available for MoMA viewers to take with them.

A related work, Cornered (1988), explores racial ambiguity through a lecture format. Piper speaks on a video monitor that is barred by an overturned table and flanked by her father’s two birth certificates. One identifies his race as white, and the other as the outdated term octoroon. Piper speaks to the audience in a measured, professorial tone: “I’m black. Now, let’s deal with this social fact, and the fact of my stating it, together.”

Although many of her works take on administrative or pedagogical formats, Piper’s work betrays an emotional rawness that is rare for artists—especially conceptualists. In the installation The Big Four-Oh (1988), a video shows a 40-year-old Piper dancing for 47 minutes straight with her back to the camera. Materials placed around the video evoke a hard life lived: baseballs, chunks of armour, and most poetically, jars of blood, sweat, tears, piss and vinegar.

Adrian Piper, Safe #1-4 (1990) Adrian Piper Research Archive Foundation Berlin

Piper re-examines her identity to this day, never resting comfortably in any category. A recent digital work, Thwarted Projects, Dashed Hopes, a Moment of Embarrassment (2012), announces Piper’s decision to “change her racial and nationality designations”. Underneath a garish four-colour portrait with darkened skin colour, she announces (in bureaucratic language) her revised racial designation as “6.25% gray, honoring [her] 1/16 African heritage”. The exhibition concludes with her Probable Trust Registry (2013), tasking the viewers to sign contracts promising to always be too expensive to buy, mean what they say and do what they say they will do. Here, her interest in speech acts turn back to Kantian questions of a moral life.

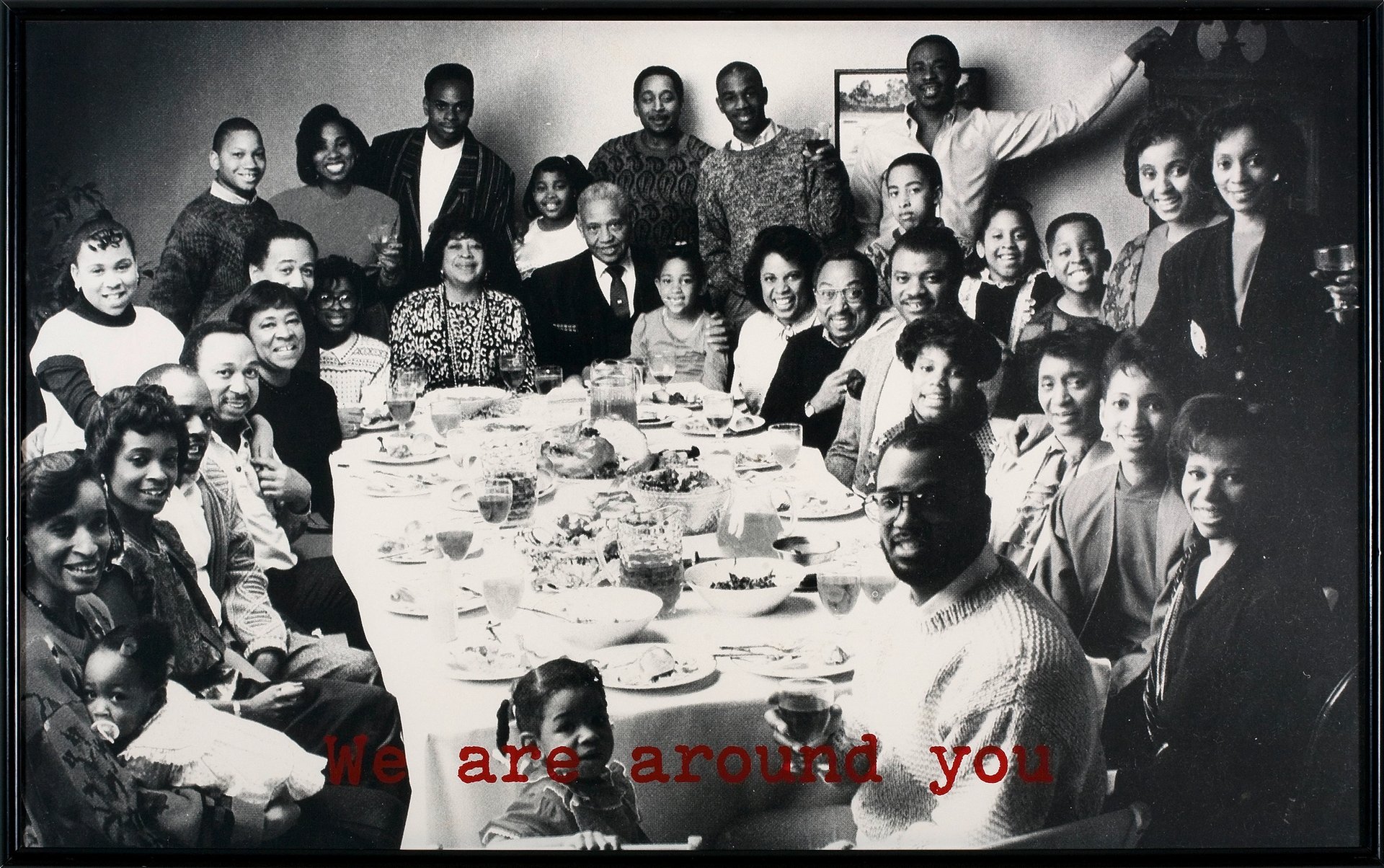

Piper’s five-decades-long practice continues to be provocative. Using direct addresses but never resorting to easy platitudes, she demands critical engagement from her viewers. Piper wields identity politics as a weapon, yet often turns the discussion back on herself. In this way, she becomes a projection screen for the audience’s collective wishes, hopes and fears.

Adrian Piper, Adrian Moves to Berlin (2007) Adrian Piper Research Archive Foundation Berlin