The great city of Troy, made famous by the ancient Greek poet Homer, was assumed to have been a real place much as Biblical stories have long been taken to be true. That the Bible was written in a poetic prose and that The Iliad and The Odyssey were both epic poems—all forms of literature, distinct in style from historical writing—did not dampen the belief that these were grand retellings of real events.

Questioning such “historical facts” due to a lack of empirical evidence began during the Enlightenment in the 17th and 18th centuries, but truly gained momentum with the rise of “critical history” in the early 19th century, when ancient texts were studied and compared to highlight contradictions and inconsistencies. The likes of Pliny and Strabo recorded stories that they had heard, or about which they had read, not all of which they had personally experienced—and many of which we now know to have been inaccurate or wholly invented. The Hanging Gardens, for example, appear likely to have existed, but not in Babylon, as Josephus and others wrote, but in Nineveh.

The same thing seems to have happened with the city of Troy and the Trojan War. What ancient thinkers assumed to have been a real place, Enlightenment thinkers assumed to be legendary, like the Greek myths. Some early modern writers attempted to assign a known ruin to Troy, with candidates including Alexandria Troas and Pinarbaşi, both in modern-day Turkey—which turned out to be fairly good guesses, as the former is 20 km and the latter only 5m from what would turn out to be the real location. In 1822, the Scottish journalist and geologist Charles Maclaren identified the correct site, called Hisarlik, on the country’s northwest coast in today’s Biga peninsula, which was published in academic journals after surveys were made in 1866 by the English consul and amateur archaeologist Frank Calvert.

Ruins in the Unesco recognised archaeological site of Troy in Turkey Photo: Umut Özdemir/Ministry of Culture and Tourism, Turkey

The German archaeologist Heinrich Schliemann was convinced by Calvert that this was the right spot, and he received permission to excavate the site from the Turkish government and started in 1878. The find was extraordinary, but complicated. There was not one lost city there but several, successive cities, dating from the Bronze age through the Roman period. One of the layers of ancient city was dubbed by Schliemann as Troy, and the rich findings, many in gold, were dubbed “Priam’s Treasure”, after the king of Troy at the time of the Homeric Greek siege. It seemed like a major coup, and it raised Troy from the realm of mythical history into the empirical zone of history proper. What was once believed to be a true, then dismissed as legend, had now yo-yoed back to truth, this time backed by hard evidence.

But that is not the end of the story.

Schliemann’s methods in excavating the various strata of cities have been condemned by modern scholars as having caused irreparable damage to the site, destroying as much or more than it unburied. The Classical scholar Kenneth Harl has even joked that Schliemann did to Troy what the Greeks had failed to do during their siege: level the city walls. It also became unclear which of the many ancient cities found on the site was the Troy. Later archaeologists, with a subtler hand than Schliemann’s, announced that at least nine cities were evident on the site, in a complex layer cake of excavations, which included some 46 sublevels.

Which layer, if any, was Homer’s Troy (if that Troy ever existed?) Archaeological evidence of a battle dating to around 1250BC was found, as well as a defensive ditch that may have surrounded the external walls of the city. This dating could fit with the general consensus on when the siege took place, though this is merely a guess. Scholars don’t even know when Homer lived and wrote his epic works, with theories ranging from the 12th through the 8th centuries BC.

Moreover, the layer of city referred to as Troy VI (the one destroyed around 1250BC), was most likely destroyed by an earthquake, not a Greek army. Throughout all the excavations, only a single arrowhead was found, and no skeletal remains, making it highly unlikely that a high-body-count war took place there. The likelier candidate is called Troy VIIa, which was the site of a battle, with evidence of extensive fire, on both the stones and skeletons found there, dated to around 1184BC. Made a UNESCO World Heritage site in 1998, this is as close as one can get to seeing the Troy of legend.

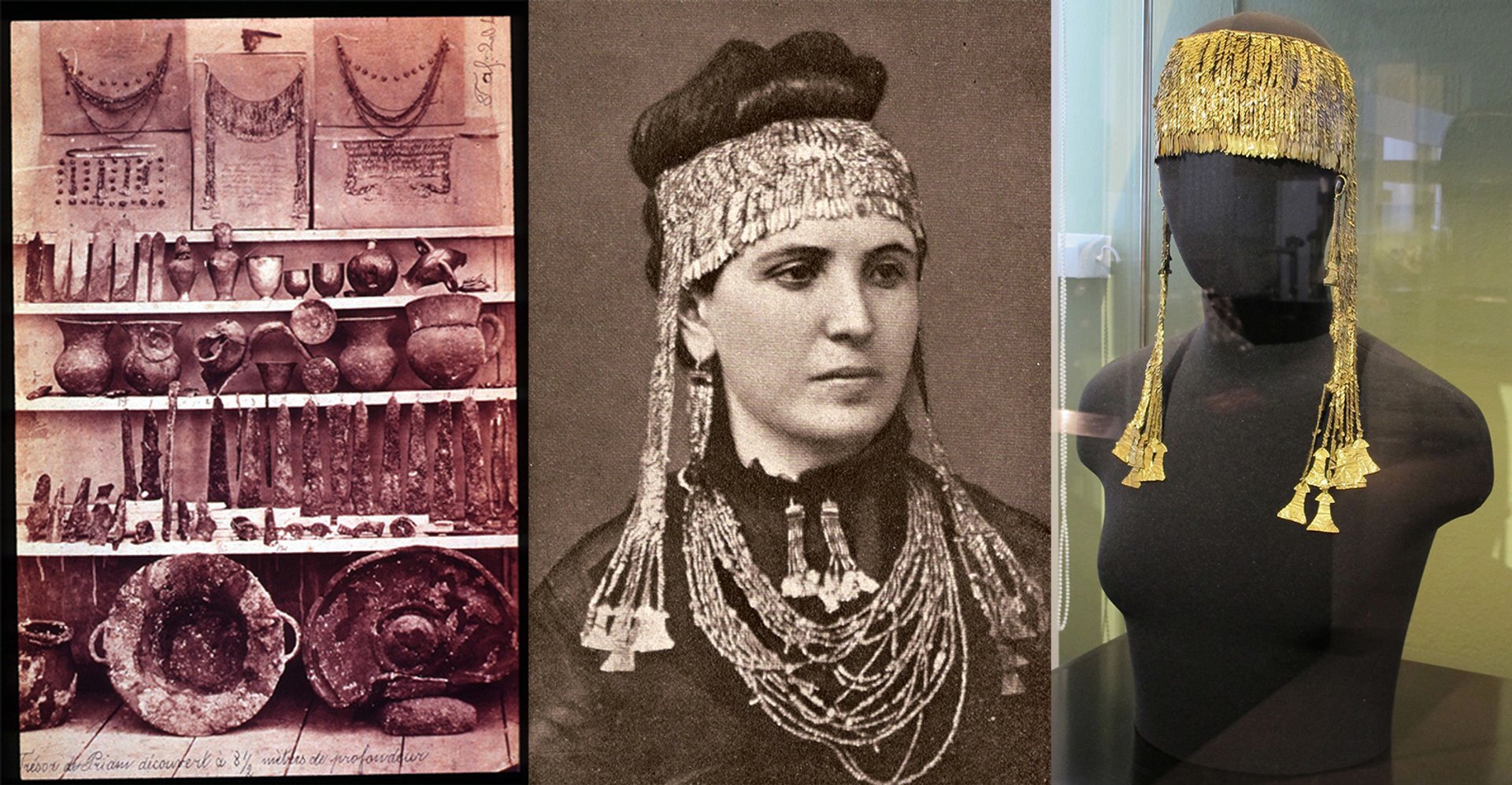

The yo-yo continues, however, with the gold horde known as “Priam’s Treasure”. This included a pair of gold diadems (referred to as the “Jewels of Helen”), 8,750 gold rings and scores of objects in gold, silver, copper and electrum (a gold, silver and copper mixture). Schliemann smuggled these out of Turkey in his personal effects and—in a move that was considered less-than-professional even then—had his wife photographed wearing much of the jewelry, which is how Ottoman officials learned that the treasures had been carried off. Most of this collection eventually went to the Royal Museums of Berlin, but Schliemann returned some of the items to the Ottomans in exchange for permission to return to Troy to dig further (he had been banned from the site for running off with his findings).

Schliemann identified a hoard of gold objects he found at the site as “Priam’s Treasure”, including a pair of gold diadems, referred to as the “Jewels of Helen”. He smuggled them out of Turkey and, in an ill-judged publicity stunt, had his wife photographed wearing much of the jewelry. The works were looted again by the Red Army during the Second World War, and are now in the Pushkin Museum in Moscow

Later archaeologists believe that this haul dates to Troy II, and therefore predates by a millenia the layer of the city that was most likely ruled by Priam. Thus the treasure remains great, but it can no longer be assigned to the era of Homeric Troy.

In 1945, during the Second World War, Priam’s Treasure was hidden by German officials underneath the Berlin Zoo, but that did not stop the Red Army from finding it. While the Soviet Union denied having the horde for decades, they were finally identified as part of the collection of Moscow’s Pushkin Museum in September 1993. A protracted plan to return the treasure to Germany—which, it could be argued, should not have had it in the first place, since Schliemann smuggled the objects away from the Ottomans—has been blocked by Russian officials, who consider the looted art as compensation for the vast damage, in goods and lives, wrought by the Nazis.

So, while the hoard can no longer be considered technically lost, Priam’s Treasure remains so, for while this is an impressive find, it was made a good thousand years before Priam walked Troy’s walls. If Priam ever existed. And if Homer’s poem was ever meant to be considered a historical record.

• Noah Charney is an author and art history professor at the ARCA Postgraduate Program in Art Crime and Cultural Heritage Protection. His new book is Museum of Lost Art, published by Phaidon

The Greek hero Odysseus slits the throat of a Thracian warrior outside the walls of Troy in this Chalcidian Black-Figure Neck Amphora J. Paul Getty Museum