Complex issues are raised by the French president Emmanuel Macron’s talk of returning cultural goods in his country’s public collections to their place of origin.

First, there are questions of legal title. In the UK, the ownership of items in state collections is normally vested in the museum’s trustees, but they are subject to statutory restrictions on disposal. So too in other Western countries, including France. But where there are questions as to legal title, as in the case of Jewish-owned properties expropriated or sold under duress between 1933 and 1945, museums and governments must be open to legal challenge. Legislation has provided for this in the UK.

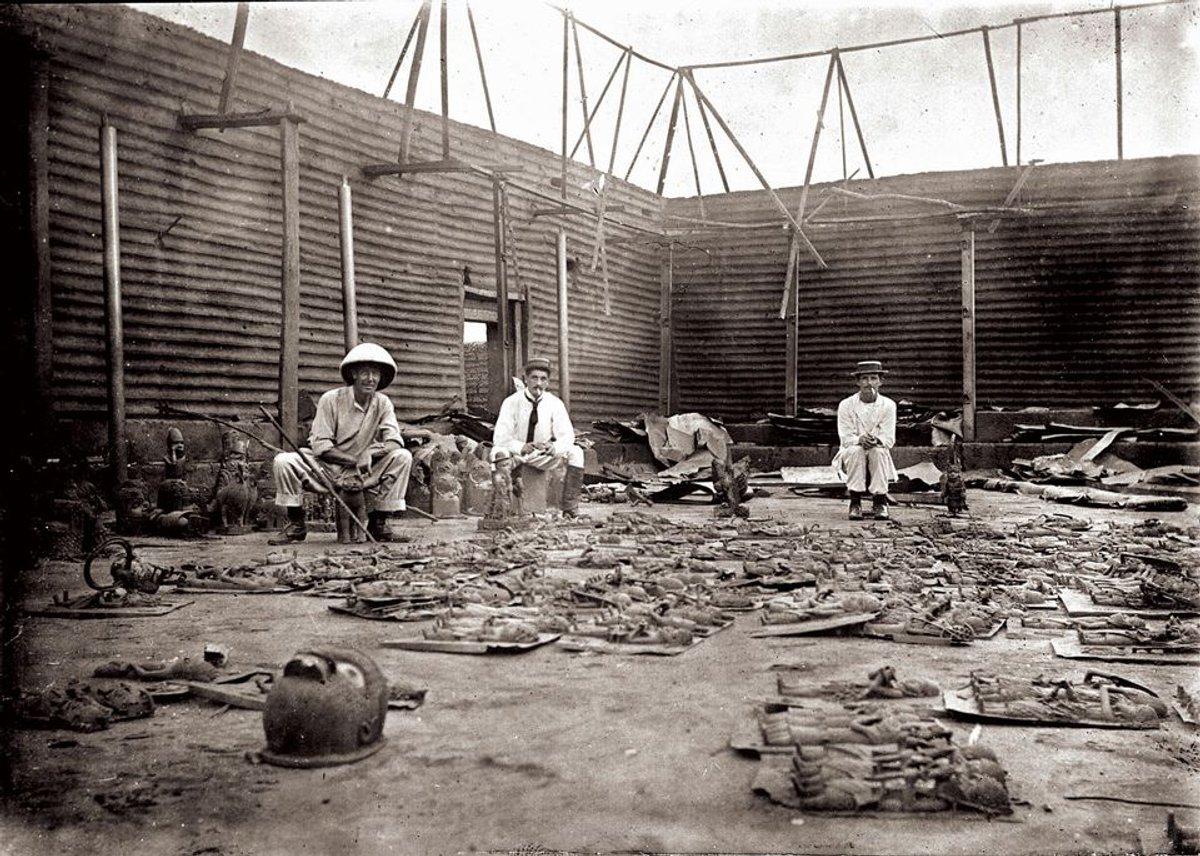

Second, there are questions of ethics. One set of issues concerns the circumstances in which particular items were originally obtained. The retention of items obtained by “looting” or as “spoils of war” must be ethically problematic.

Another set of issues concerns the category of “works of art” and even that of “cultural goods”. Is an object of religious veneration or the skull of an ancestor sufficiently described as a “work of art” or even a “cultural good”? Another ethical consideration might refer to historical change in the places of origin of such goods. What do ancient Near Eastern cultural remains have to do with predominantly Muslim cultures? In what sense is the Pergamon Altar “Turkish”? Do the Parthenon Marbles “belong” to modern Greece any more than they do to Hellenised Europe at large? It may be impossible to formulate ethical principles to cover all such issues in general terms, and it would seem that a case-by-case approach will always be necessary.

Third, there are questions that may be described as “prudential”. There is no doubt that many fragile “cultural goods” owe their survival to their transfer to Western public collections. They may well be exposed to new hazards if they are returned to their place of origin: consider what might have happened in recent years to items returned to Iraq and Syria in the immediate post-colonial period. Will “cultural goods” returned from Western public collections remain in public ownership after they have been returned? Is there any comparably permanent guarantee of appropriate conservation arrangements? It may be politically incorrect to raise such questions, but the risks are real and they should be reckoned with.

Finally, there are questions of access. It has been argued that the presence of an item in a large Western collection guarantees the possibility of intercultural comparison and the mutual enrichment of the understanding and appreciation of each such item. While this argument prompts the question of whether all such items should be regarded simply as “cultural goods”, there is, however, no doubt that Western collections are much more widely accessible to visitors, to experts and, indeed, to pilgrims, than are most museums elsewhere. There is also a sense in which the great Western collections secure access for future audiences and their unanticipated questions: would the discovery of the common African origins of mankind have been possible if every skull and bone had been returned for interment with its ancestors before the discovery of DNA?

Trustees of museums and even parliamentarians are likely to be increasingly exposed to emotionally charged and high-volume calls for the return of cultural goods to their places of origin. Sometimes legal considerations will apply. There are serious ethical issues to be pondered. And at the same time, considerations of prudence, accessibility and preservation for the future must also be taken into account. There should, however, be no place for grandstanding and virtue-signalling.

Robert Jackson is a former UK minister for higher education and science