As tensions between Iran and the US intensify, with President Donald Trump’s nuclear deal deadline looming and a Supreme Court hearing over his travel ban on eight mostly Muslim countries, a groundbreaking exhibition mixing historical and contemporary Iranian art opened to VIP guests in Los Angeles last night.

Speaking at the launch at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (Lacma), the curator Linda Komaroff says she hopes the show will change perceptions of Iran in the US. “I hope to show American audiences the human face of Iran, and to encourage us to question what we see in the news,” she says.

Inspiration for the exhibition, titled In the Fields of Empty Days: The Intersection of Past and Present in Iranian Art (6 May-9 September), came in 2014 when Komaroff was driving past Vali‘asr Square in Tehran.

There, she was startled to see a huge billboard of then President Barack Obama standing next to Shimr, a malevolent figure in Shi’ite early history who offered refuge to and then murdered the Imam Husain at Karbala in Iraq. The image was, Komaroff argues, a symbol of Iran’s mistrust of Obama. “To liken someone to Shimr is the lowest insult,” she says.

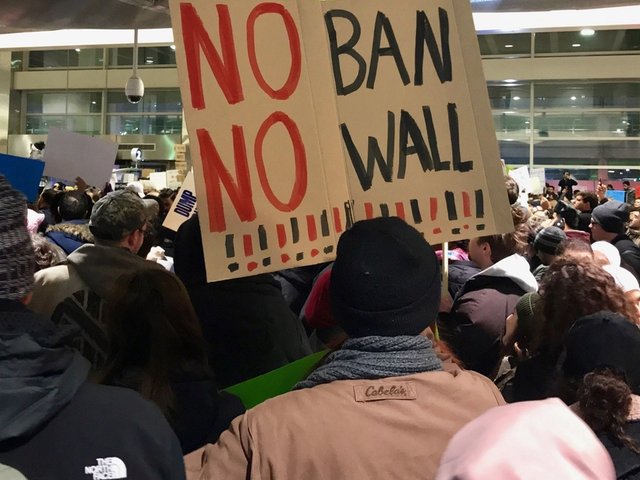

If relations between the US and Iran were strained in 2014, the exhibition opens during even more urgent times. Last week, the US Supreme Court heard oral arguments in a case challenging the third iteration of Trump’s travel ban, which has been imposed on Iran, alongside seven other mostly Muslim countries. Lacma is one of more than 100 US museums to have signed an amicus brief opposing the ban.

Artists born in Iran and now living in the US including Pouya Afshar, Koushna Navabi and Nourredin Zarrinkelk attended the opening, as did those born in the US such as Asad Faulwell and Taravat Talepasand.

However, notably absent were artists who are based in Iran. “The travel ban has not impacted the exhibition in terms of loans, because the works were already here,” Komaroff says, noting that more than half of the 125 pieces on show come from Lacma’s own collection of Middle Eastern art. “But it would have been great if artists could have enjoyed the show for themselves,” she says.

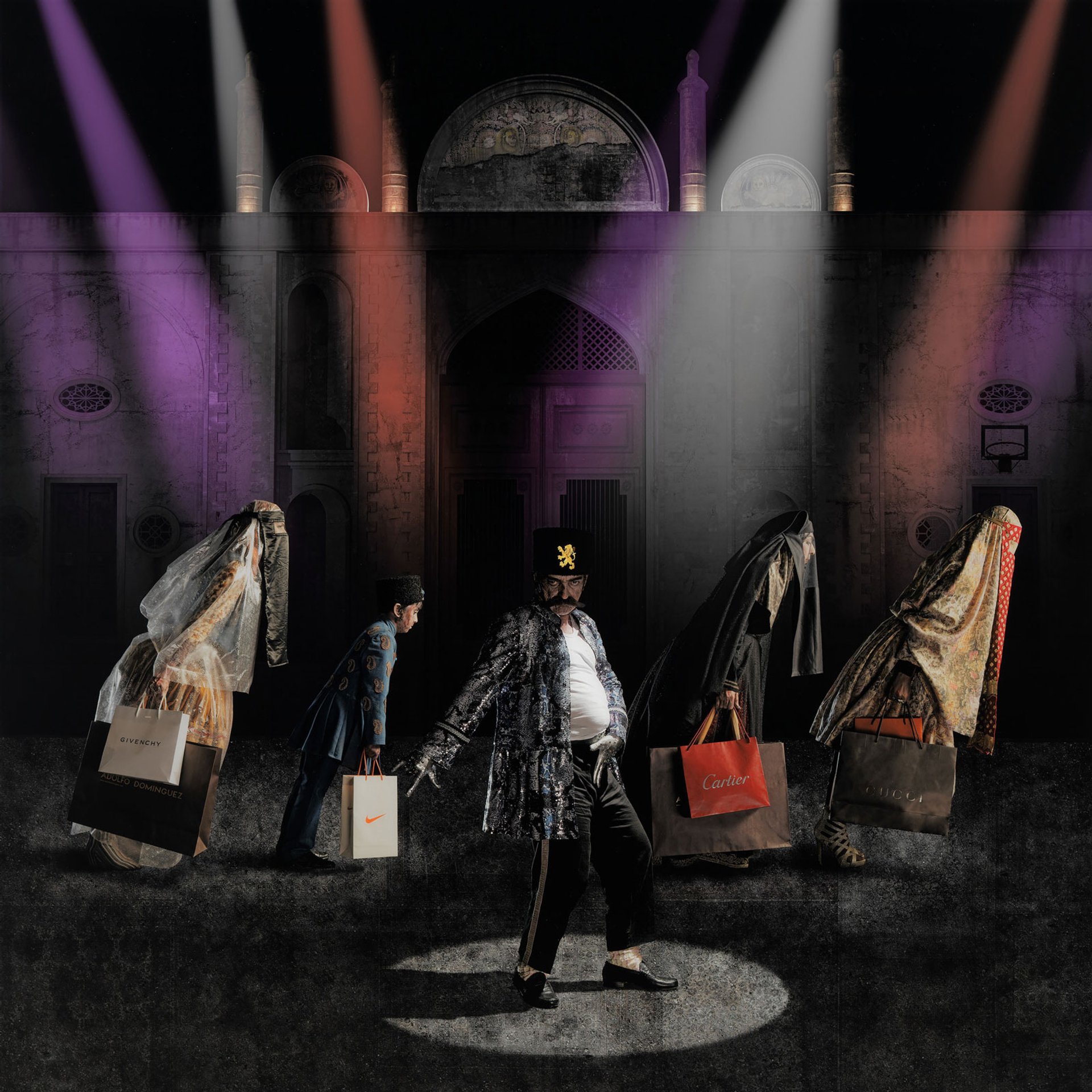

Their voices are nonetheless amplified through the exhibition, which covers a broad spectrum of Iranian art, including Safavid manuscript illustrations as well as Qajar-era photographs. The emphasis is, however, on works made just before the 1979 Islamic Revolution and in the decades since. “Iranian artists have a tendency to take the present and hide it in the past to use it as a form of political commentary,” Komaroff says.

A series of photographs, titled Underground (2014) by Siamak Filizadeh, takes as its cue the long reign of Nasir al-Din Shah, including his assassination and the execution of his murderer, Mirza Riza Kirmani. Elements of contemporary life creep in: onlookers record events on mobile phones or an ATM hovers on the edge of another scene.

Siamak Filizadeh, Return from Europe from the series Underground (2014) Siamak Filizadeh, digital image © Museum Associates/LACMA

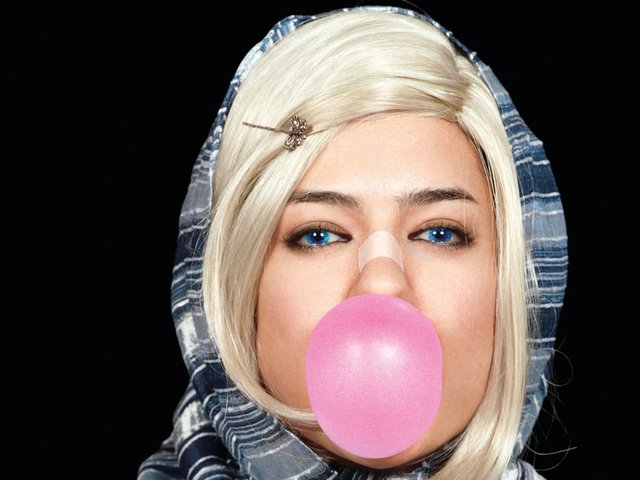

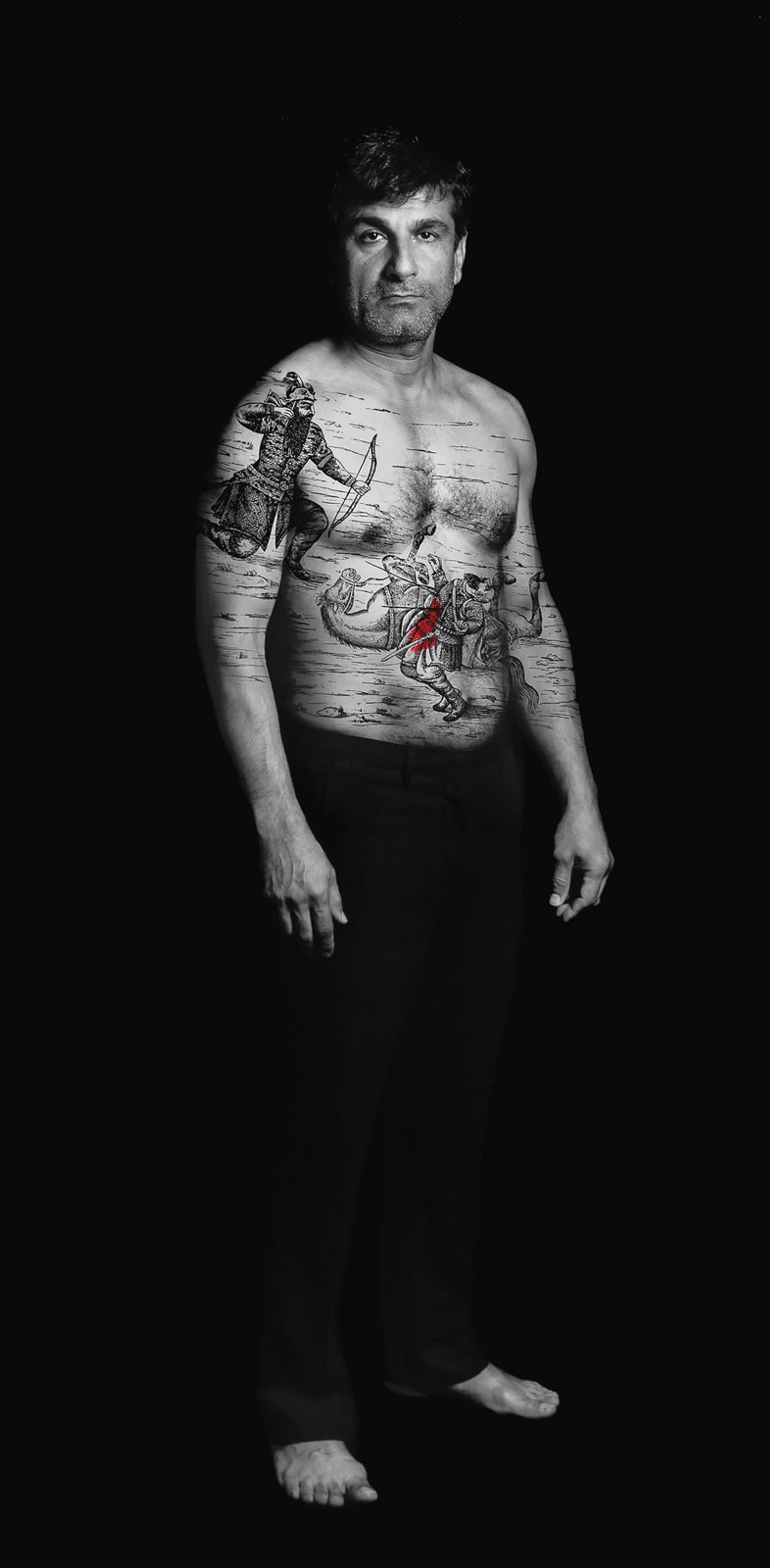

Created in 2012 in response to the Arab Spring uprisings a year earlier, Shirin Neshat’s photographic series, The Book of Kings, references the ancient book of Shahnameh, an epic composed by the Iranian poet Hakim Abul-Qasim Mansur (later known as Ferdowsi Tusi). “Shirin takes imagery [from the Shahnameh] and applies it to the bodies of the figures she depicts like tattoos,” Komaroff says. “Its importance is literally pouring out of their skin.”

Shirin Neshat, Amir (Villains) from the series The Book of Kings (2012) Shirin Neshat, photo courtesy of the artist and Gladstone Gallery, New York and Brussels

Meanwhile, delicate polaroids by the photojournalist Kaveh Golestan, who was killed in Iraq in 2003, morph 19th-century figures into monsters. “They are a commentary on the Pahlavi dynasty using 19th-century imagery,” Komaroff says.

Kaveh Golestan, The Shah Left (1979, printed 2015) Estate of Kaveh Golestan, digital image © Museum Associates/LACMA

Michael Govan, the director of Lacma, says the exhibition makes the point that the current political moment is nothing new. “If you look at long stretches of time, you can pull out themes of humanity, power and myth, stories repeat themselves,” he says.

But Govan acknowledges the damaging effects of political actions and embargoes on museums. “We can’t borrow art from Russia right now,” he says. “It’s a great frustration to art museums in particular, because our content is cross-cultural discussion. Our very reason for being is to understand many cultures.

“Not only should artists and art be encouraged to travel in times of political tension, art carries much of the deeper histories of culture that help us to understand conflict, if not to solve it.”