We might call them “invisible masterpieces”. Works that we cannot see, because they vanished long ago. But their presence remains as an influence to those who did see them, sometimes centuries back. The frescoes that once adorned the exterior of Venice’s Fondaco dei Tedeschi were such works.

Venice’s Fondaco dei Tedeschi

The Fondaco (derived from the Arabic word for “storehouse”) was a center for merchants, this one for those of Germanic origin (Tedeschi), although the term encompassed much of northern Europe, not only what we think of as modern-day Germany. The ground floor was a place to do business but the building also contained living quarters, both long- and short-term, for those in Venice on business—some 160 of them at a time. Originally constructed 1228, the Fondaco we see today was completed in 1508, after a fire consumed the earlier structure. The year it was completed, a dazzling series of frescoes were unveiled on the façade facing the Grand Canal, made by a pair of young Venetian artists—Titian and Giorgione—who were 20 and 30, respectively, when the work was made.

The two were the rising stars coming out of the studio of the best of all Venetian painters, Giovanni Bellini. But shortly after they completed the Fondaco frescoes, their lives careened in very different directions. Giorgione was dead within two years, cut down by plague. He made very few works during his abbreviated career (fewer than 20 have survived, though the exact number varies depending on which art historian you ask), so anything by Giorgione is hugely valuable—far more than the work of the wildly prolific, long-lived Titian. He lived into his 80s, was the master of a large and thriving studio for decades, with an influence extending to the court of Spain, and he made scores of paintings.

Mysteries surround the relationship between Giorgione and Titian. Some have even theorised that Giorgione might have never actually existed and was instead a pseudonym used by Titian. Conspiracy theories aside, the two were part of Bellini’s studio, with Giorgione the older and more established artist at the time the Fondaco was painted. When he died, probably in October 1510, Titian finished several of his pieces (exactly which one, and to what extent, remains a hotly debated question by scholars). Thus, the legacy of the two remains intricately linked, but nowhere more so than in a fresco cycle that we can no longer see, thanks to the relentless Venetian dampness.

It is a bad idea to paint in fresco in a city immersed in water. The humidity of Venice is such that the murals were already fading, the plaster on which they were painted flaking off, within decades of their completion. Vasari wrote, in 1550: “I know of nothing more harmful to fresco painting than the sirocco, especially near to the sea, where it carries salt moisture with it.” In Venice, only mosaics are a safe bet to last.

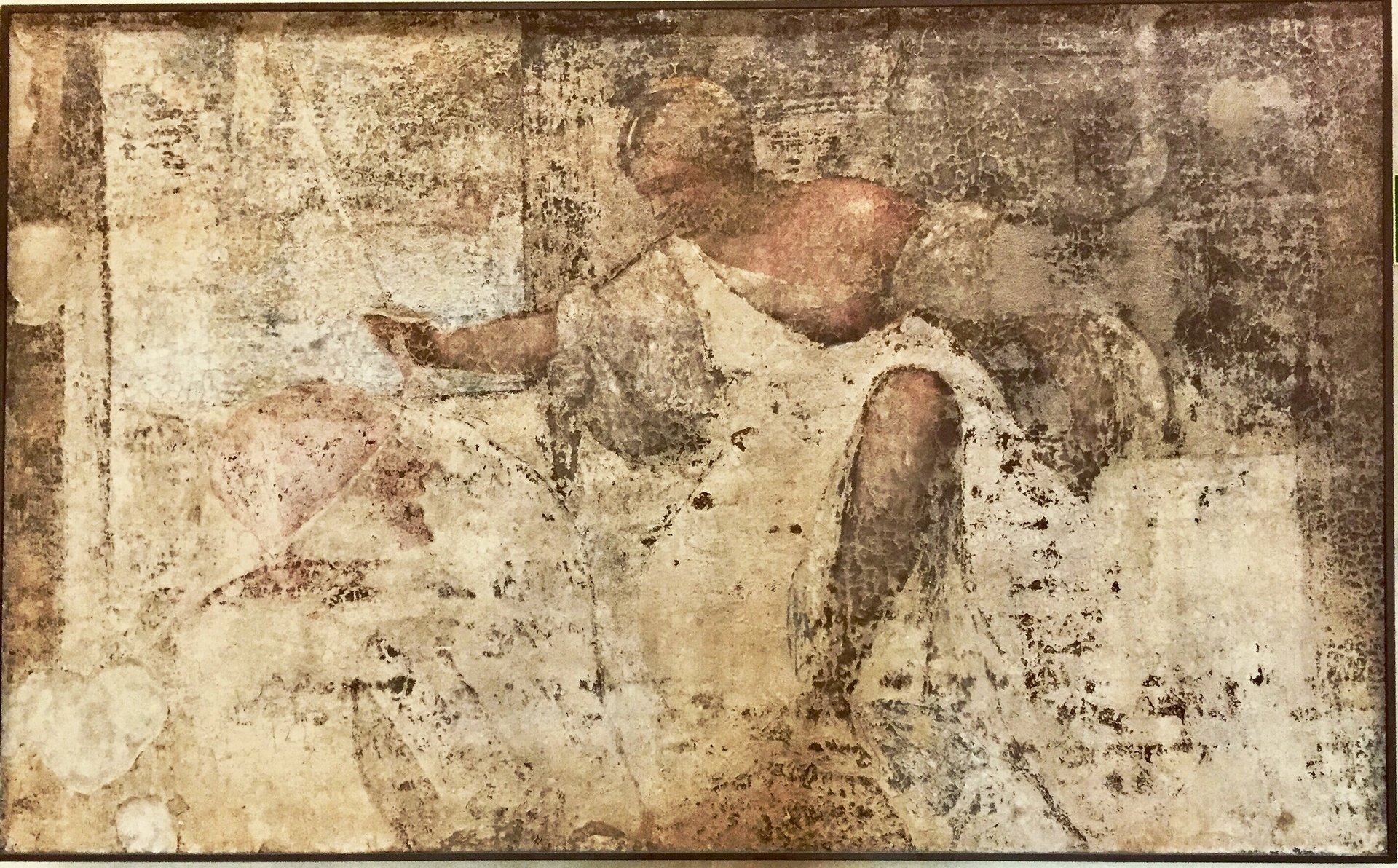

A fragment of Giorgione and Titian's central fresco for the Fondaco dei Tedeschi, now preserved in the Galleria Francetti in Venice

A print of the Fondaco dei Tedeschi's main mural showing a female figure seated brandishing a sword and trampling on a man's head, made by Giacomo Piccini in 1658 Courtesy of the British Museum

In 1966, what remained of the frescoes was removed and transferred to the safety of a gallery, and scholars have sought to reconstruct the full cycle from these fragments. As with most things related to Renaissance art, the first stop for researchers is Vasari’s Lives of the Artists. He describes the central image above the main doorway of the Fondaco as a seated woman holding a sword and the severed head of a giant (perhaps Judith with the head of Holofernes), “speaking to a German standing below her”. A 17th-century print, ostensibly based on the fresco, shows as much, with the German dressed in armour and concealing a dagger behind his back. (One wonders what message the German merchants of Venice were hoping to convey, if indeed this was the main image above the entrance to their storehouse.) And there is a serene and elegant Judith with the Head of Holofernes by Giorgione, painted in 1507 and now held in the Hermitage in St Petersburgh, which could be linked to the fresco.

Above the seated female figure, who could also represent the embodiment of Germania (all these interpretations are open to interpretation) were a pair of nude women, a figure accompanied by the head of a lion, and an angelic putto, holding a short staff and painted near some apples.

Some have suggested that the frescoes referred to the Twelve Labors of Hercules, which would make the seated woman Alcmena, the hero’s mother, the severed head that of his cousin Eurystheus, whom he served in penance, the lion is then the Nemean lion, the putto is actually Mercury, the apples refer to the Hesperidean apples stolen in the labor of Atlas, and so on. It’s a compelling idea with a frustrating punchline—we just do not know, because insufficient evidence survives. The frescoes themselves are too fragmentary, derivative works such as prints are incomplete or of suspect accuracy, and the textual references (like Vasari’s) must be taken with a grain of salt, as we do not know how complete or accurate they are, or whether the authors actually saw the frescoes in person.

A 19th-century watercolour sketch of the frescoes by the artist Zaccaria dal Bo

The painting would have encompassed the Fondaco’s entire façade, wrapping around the windows, integrating the architectural elements and including some painted trompe-l’oeil. A 19th-century watercolourist, Zaccaria dal Bo, did sketches of what was left of the frescoes, which are atmospheric but lack detail, perhaps because the frescoes themselves were too faded by that point.

When completed, the Fondaco was a wonder of Venice and the frescoes were the talk of the city. They solidified Giorgione’s reputation and helped to launch Titian, just a lad of 20 at the time. But the damage that the sirocco wind wrought within decades of their completion means that their influence and memory was fleeting. They are one of the great invisible masterpieces, a key to history but one which has long ago melted away against Venice’s hot canals and saline breezes.

• Noah Charney is a professor of art history and the author of Stealing the Mystic Lamb: the True Story of the World’s Most Coveted Painting