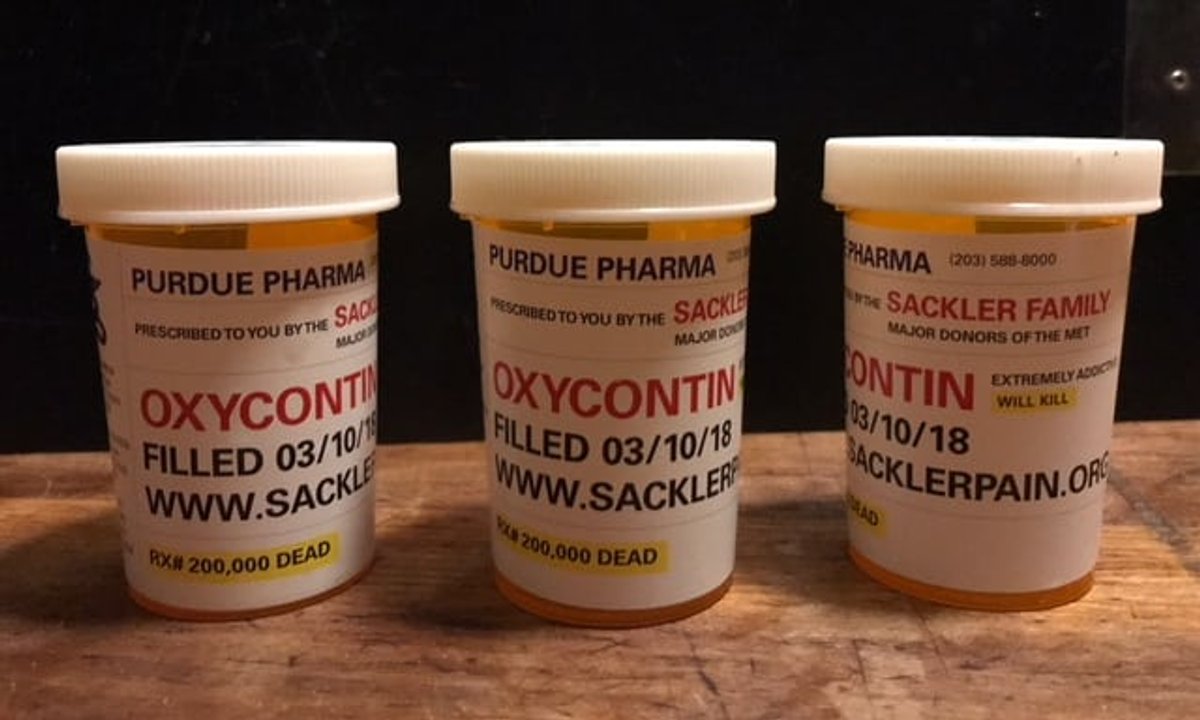

Nan Goldin and her anti-opioid activist group PAIN led their first protest at the Metropolitan Museum’s Sackler Wing on Saturday afternoon, tossing prescription pill bottles labelled OxyContin into the moat surrounding the Temple of Dendur and unfurling banners that read “Shame on Sackler” and “Fund Rehab”. The popular wing of the museum was funded and named after the three Sackler brothers, Arthur, Mortimer and Raymond, who bought and built up Purdue Pharma, the maker of Oxycontin, and whose heirs are today known for their arts and cultural philanthropy.

“In the name of the dead. Sackler family. Purdue Pharma. Hear our demands. Use your profits. Save our lives,” Goldin shouted to the on-looking crowd of visitors according to Artnews, as the protestors echoed her statements. The group also handed out pamphlets with facts about the US opioid crisis and demands for Purdue Pharma and the Sackler family, including funding for treatment and addiction education. “Unfortunately this wing is tainted with the blood money of the Sackler family who lied and profited off the sales of the prescription opioid Oxycontin,” the pamphlet reads in part. “It’s time for the family that helped create this problem answer to the people worst affected.”

Goldin launched the group PAIN in January after sharing her own addiction story in Artforum magazine. “I became absorbed in reports of addicts dropping dead from my drug, OxyContin. I learned that the Sackler family, whose name I knew from museums and galleries, were responsible for the epidemic,” she wrote. “This family formulated, marketed, and distributed OxyContin. I have decided to make the private public by calling them to task.” Her first step was to create an Instagram group to raise awareness and then she launched an online petition, which has received nearly 35,000 signatures. Artists including Ryan McNamara and Jeremy Deller have spoken in support of Goldin’s movement. Saturday's peaceful protest was the first direct action by the group.

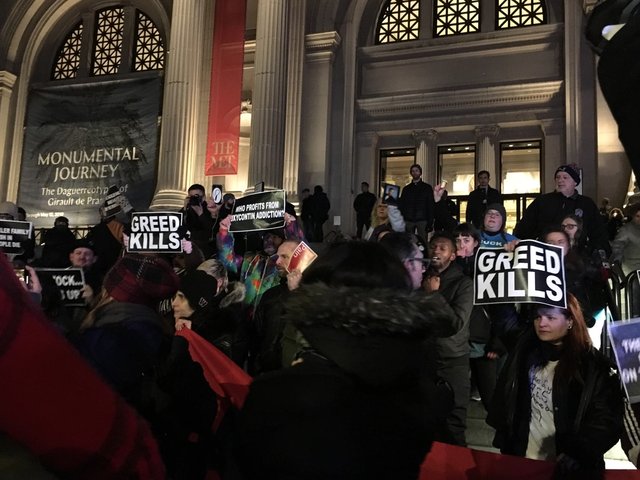

Towards the end of the event, the demonstrators staged a “die-in”, dropping to the floor and reciting “Sacklers lie, people die”. They continued the chant as they left the museum, gathering on the Met’s front steps for a final statement from Goldin, according to the New York Times: “We’re just getting started. We’ll be back.”

UPDATE: In a statement, Jillian Sackler, Arthur's widow, said: "Much of what’s been written in recent months about my late husband, Dr Arthur M. Sackler, is utterly false. Arthur died nearly a decade before Purdue Pharma—owned by the families of Mortimer and Raymond Sackler (his brothers)—developed and marketed OxyContin. At the time of his death in 1987, Arthur was lauded for his contributions to medical research, medical communications and museums. He was a renowned art collector and connoisseur, and because of this, we have the Arthur M. Sacker Gallery of Chinese Stone Sculpture at The Met, the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery at the Smithsonian, the Arthur M. Sackler Museum at Harvard, the Jillian and Arthur M. Sackler Wing of Galleries at the Royal Academy and the Arthur M. Sackler Museum of Art and Archaeology and the Jillian Sackler Sculpture Garden at Peking University. None of the charitable donations made by Arthur prior to his death, nor that I made on his behalf after his death, were funded by the production, distribution or sale of OxyContin or other revenue from Purdue Pharma. Period.

Further, as a physician and medical scientist, Arthur was moved by a curiosity and desire to improve lives with new therapies. He made a substantial part of his fortune over 50 years in medical research, medical advertising and trade publications. His philanthropy in medicine extended to the Arthur M. Sackler Center for Health Communications at Tufts University and the Arthur M. Sackler Sciences Center at Clark University.

All these gifts, made in the 1970s and 80s, were made independently of his brothers and their families. Thus, for anyone to assert that institutions received “tainted” gifts from Arthur is ludicrous.

Passing judgment on Arthur’s life’s work through the lens of the opioid crisis some 30 years after his death is a gross injustice. It denies the many important contributions he made working to improve world health and to build cultural bridges between peoples."