The art world has always had its share of controversy, but between September 2016 and July 2017, a wave of protests had museums scrambling.

In St Louis, Missouri, locals called for a boycott of the Contemporary Art Museum (CAM) over the white artist Kelley Walker’s appropriated images of black people smeared with chocolate and toothpaste. At New York’s Whitney Biennial, protestors blocked from view and called for the destruction of the white artist Dana Schutz’s painting, Open Casket (2016), which depicts the body of the black teenager Emmett Till, who was lynched in Mississippi in 1955. That controversy led to the writing of an open letter calling for the cancellation of her show at the Institute of Contemporary Art Boston. In Minneapolis, there were demonstrations against the Walker Art Center’s installation of white artist Sam Durant’s Scaffold (2012), a sculpture that incorporated the form of the gallows used by the US Army to hang 38 Dakota men in 1862. Soon after, the opening of a Jimmie Durham retrospective at the Walker reignited a decades-long dispute over the artist’s self-identification as Native American.

All these incidents centred on one issue: appropriation. How can artists responsibly use images that are not their own, especially when those images are tied to the history of another culture? And how can museums display such work while respectfully engaging with marginalised communities?

How can artists responsibly use images that are not their own, especially when those images are tied to the history of another culture?

These are old questions, but they have taken on a new urgency. So, when Naomi Beckwith, a curator at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, was asked to chair a curatorial leadership summit at the 2018 Armory Show, it seemed like a perfect opportunity to revisit them. The topic of the 9 March day-long programme is appropriation. “Not only is it timely, but we wanted to do something specific to how curators function,” Beckwith says. “This isn’t going to be a generic conversation about culture but about what really is going to help us think and behave better as curators in the future.”

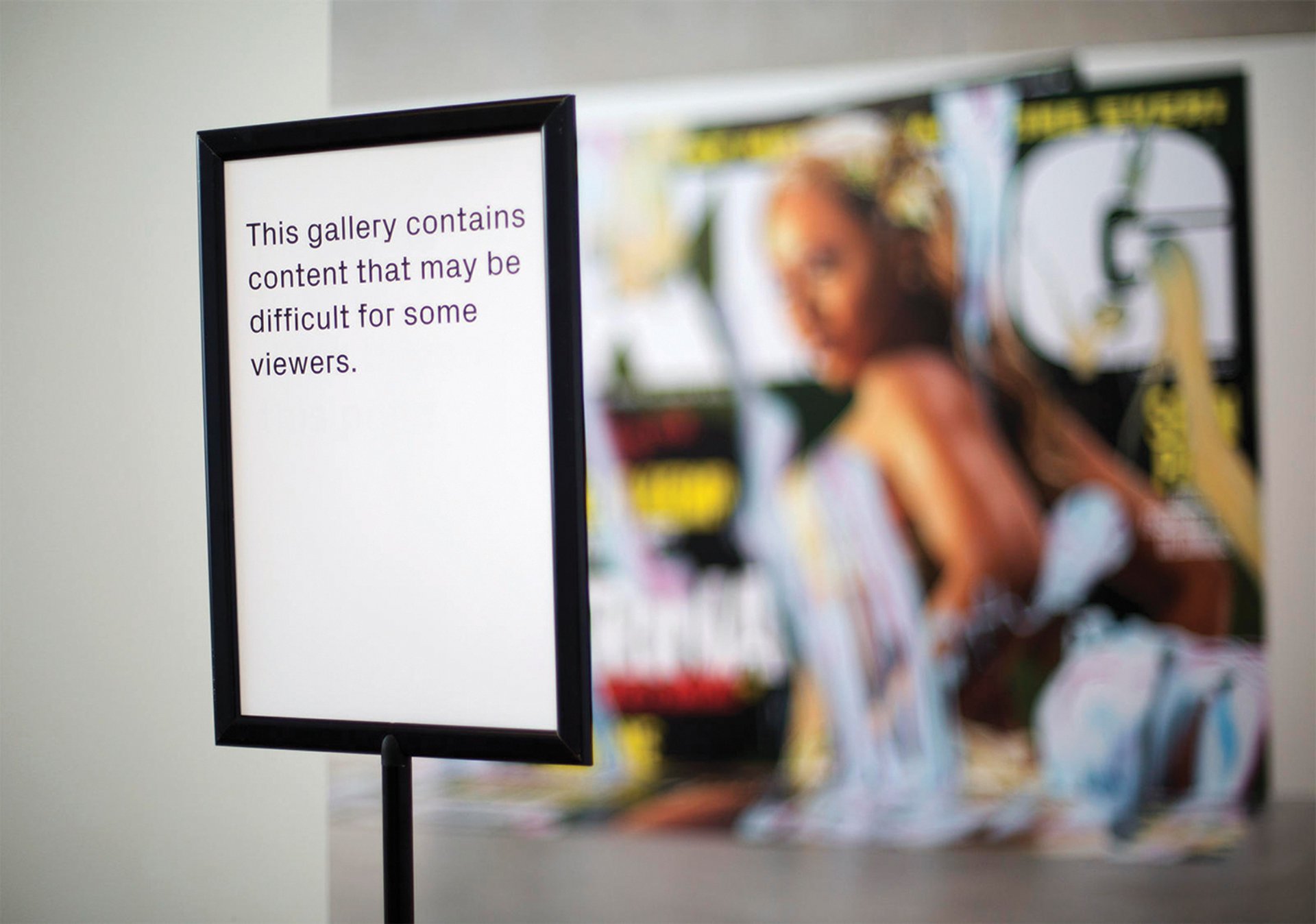

The behaviour of curators and their institutions has been the subject of much debate as recent controversies have unfolded. Attendees at the artist talk that set off the Kelley Walker uproar claimed Jeffrey Uslip, then CAM’s chief curator, was unresponsive to questions about the exhibition. Uslip left his job several weeks later, after the museum constructed a wall to block the works from immediate view and mounted a warning at the entrance to the show. The Whitney Biennial curators Christopher Lew and Mia Locks defended Dana Schutz’s painting, but in response to the protests the museum added special wall text and invited the poet Claudia Rankine to co-organise an event about the “ethics of representation”.

The most radical response came at the Walker Art Center, where the director Olga Viso and Sam Durant attended a mediation with Dakota elders. Together, the group decided to dismantle Scaffold, and the artist signed over the intellectual property rights for the sculpture to the Dakota nation, which buried the wooden remains.

“As director of the Walker, I regret that I did not better anticipate how the work would be received in Minnesota, especially by Native audiences,” Viso wrote in the Walker’s digital magazine. “I should have engaged leaders in the Dakota and broader Native communities in advance of the work’s siting, and I apologise for any pain and disappointment that the sculpture might elicit.”

A protest sign hangs on a fence surround Sam Durant's Scaffold sculpture at the Walker Art Center's sculpture garden Lorie Shaull

Viso will participate in the Armory’s curatorial summit, joining Beckwith and the artist Coco Fusco for a closed-door discussion about the “morals of representation”. “What I’d like for them to offer is a kind of case study, to offer tools,” Beckwith says. “It’s about putting things forward as a learning opportunity, so that when someone finds themselves in a situation, they can turn around and say, ‘It’s already happened at the Walker, at the Whitney. Let’s be aware.’”

“A lot of us are interested in understanding the time we’re living in and using these incidents as ways to revisit what it means to be a contemporary art museum in 2018,” says Wassan Al-Khudhairi, who is CAM’s new chief curator and will attend the Armory summit. “Do we need to be more transparent? How can we continue to be relevant?” Al-Khudhairi says she’s devoting her first year in St Louis to meeting people and being a “sponge”. She adds that while she tends to keep a global perspective, “it’s always motivated by thinking about the immediate context—the communities the museum is serving, the communities we want to be serving—and using that as a lens to see the larger contemporary art world”.

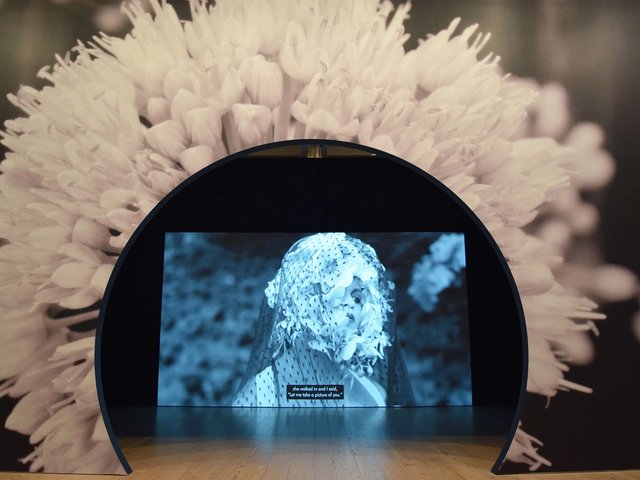

Warning signs at Contemporary Art Museum St Louis following criticism and outrage over an exhibition of work by Kelley Walker Carolina Hidalgo | St Louis Public Radio

Beckwith stresses how crucial it is for artists, curators, and others to “become more aware of and sensitive to context”. That means paying attention to geography as well as “the asymmetries of power”, she says. “Are we aware of the history that comes with material? Are we thinking about our audiences, and are we trying to balance not only what we say and what we do, but how we do it?”

While it is necessary for curators and directors to become more aware and self-critical, it is only one part of the process. After mediation, the Walker made a series of institutional pledges: to continue dialogue with Native communities; to commission a work by a Native artist; to help educate the staff, board and audiences; and “to work to make structural change”. This January, it updated those commitments with a more specific list of tasks, including improving the museum’s acquisitions process and protocol for placing art in public, and creating a Native advisory group for the commissioned work.

Structural changes such as these are important because they outlast people. At the Walker, for instance, Viso unexpectedly resigned in November “amid tensions with the board”, the Minneapolis StarTribune reported—perhaps taking some of the goodwill she had built among Native communities with her. A handful of Native artists and others have since publicly expressed concerns over her departure and what it means for their relationship with the institution.

“The problem is that when you’re one of these communities, and you have some sort of trust with these people, they retire, so then you’re having to start from scratch all over again,” says Minneapolis-based artist and curator Graci Horne, who helped organise the Scaffold protests.

We need more people in those fields to take back our own storiesGraci Horne

Horne does not have an exact prescription for what museums should be doing to avoid exploitation and improve representation, but she thinks institutions should consider introducing new language into their bylaws. She also stresses the need to hire more people of colour in curatorial and research positions. “We need more people in those fields to take back our own stories,” she says.

Increasing internal diversity is what CAM St Louis has done by hiring Al-Khudhairi, who was born to Iraqi parents in Kuwait. But the local artist Damon Davis, who first called for the boycott of the museum after attending Kelley Walker’s talk, is still wary of the apparent progress. “It’s black as fuck now,” he says of CAM, citing shows of work by Sanford Biggers and Mickalene Thomas. And while he appreciates that “finally, in a black city, when these kids come in they get to see black artists”, he questions whether the change is genuine.

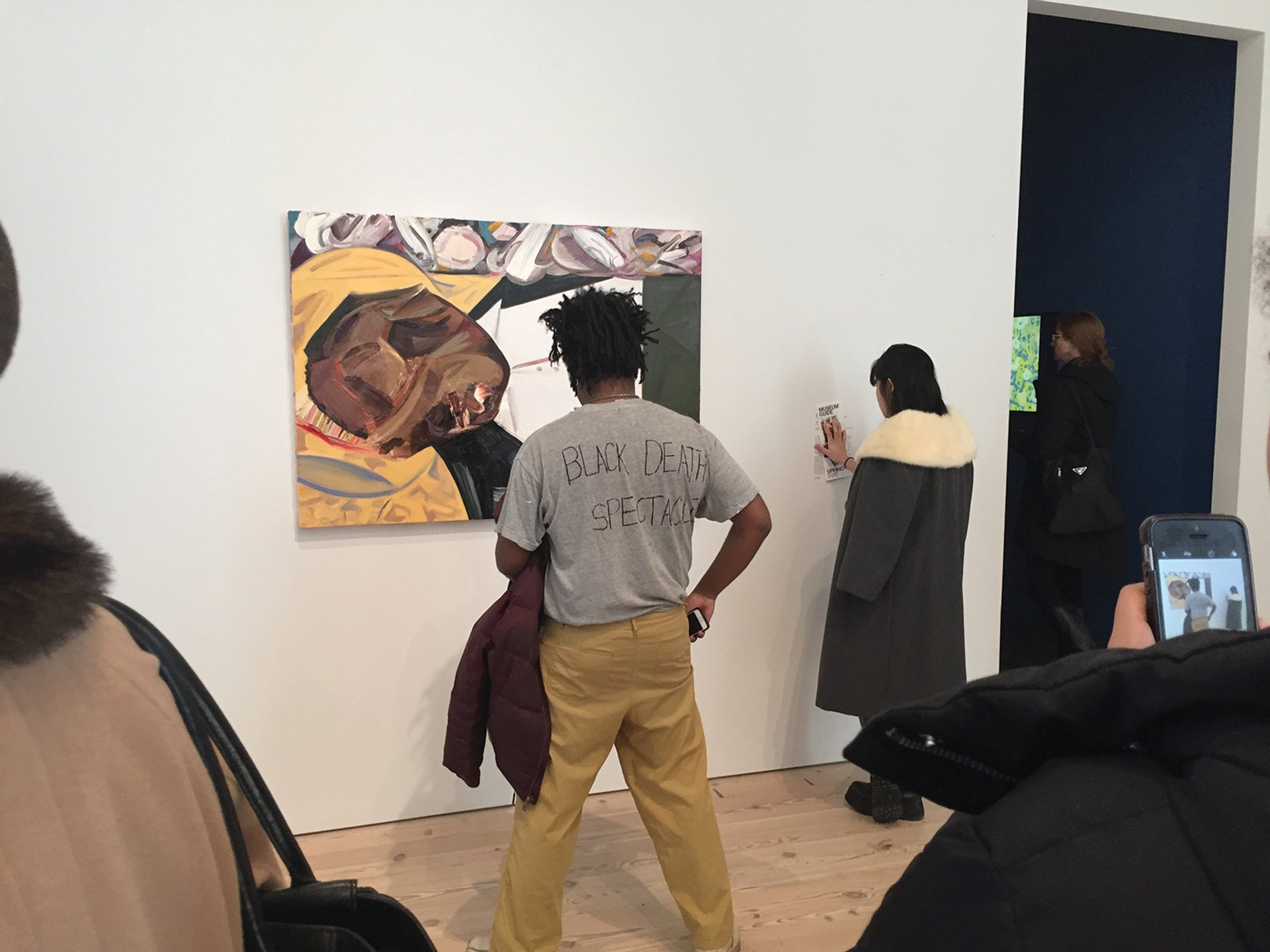

The artist Parker Bright protesting Dana Schutz's work Open Casket at the Whitney Biennial Photo: Michael Bilsborough

“I’m so jaded by the fact that [the museum] didn’t respond with empathy in the beginning,” he explains. “My Momma used to say, if I got caught doing something: ‘Are you sorry because you’re wrong, or sorry because you got caught?’”

Davis has not met Al-Khudhairi yet, but his concerns don’t centre on her anyway. “I have a problem with upper administration, the board,” he says. “Those are the faceless people who move things around, who aren’t accountable to anyone. But if something happens again, the curator is going to be the one to leave. It’s a weird chess game, and you don’t know who you’re playing against.”