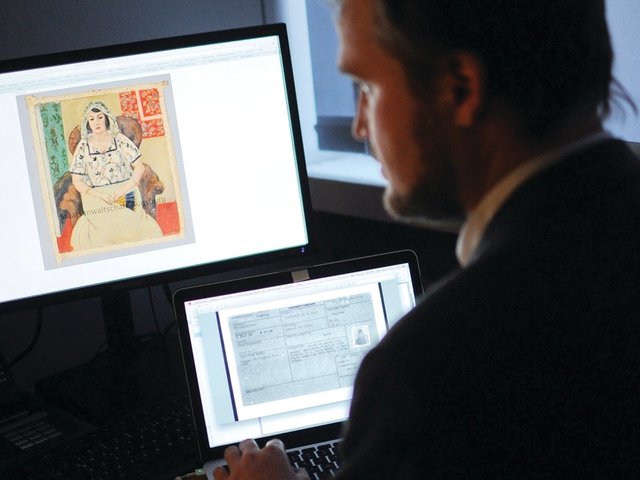

The widow of Erhard Göpel, an art historian who worked as a dealer for Adolf Hitler in occupied Europe during the Second World War and was embroiled in Nazi art-looting, has bequeathed an important collection of works by the German artist Max Beckmann to Berlin’s State Museums. Initial research into the works’ provenance by the Central Archive “gave no concrete cause for suspicion that these works were looted”, says the institution in a statement.

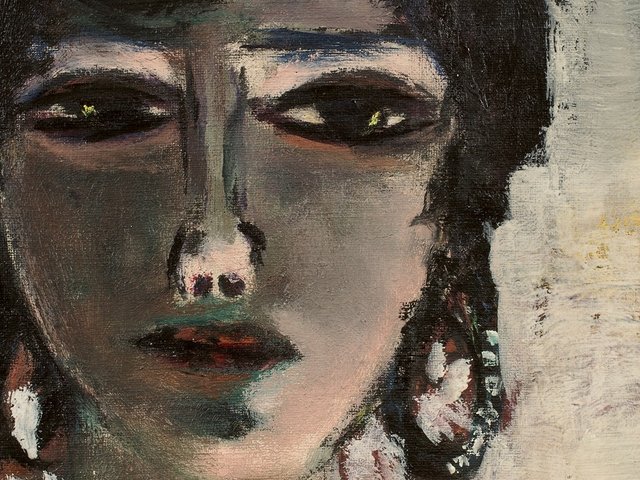

Like her husband, Barbara Göpel, who died last year at the age of 95, was an art historian. Her bequest includes a painting by the German artist Hans Purrmann, two paintings by Beckmann—a self-portrait in a bar (1942) and a portrait of Erhard Göpel (1944)—as well 46 of his drawings and 52 prints.

Erhard Göpel was a key member of the Linz Special Commission, the team of dealers who purchased—and looted—art across Europe for Hitler’s unrealised Führermuseum, planned for his home town of Linz. Göpel was instrumental in acquiring the Schloss family collection in Paris after it had been looted by the Gestapo. The collection, assembled by an Austrian-born French Jew, included works by Rembrandt and Frans Hals. After the war, Göpel evaded sentencing and spent the rest of his career organising exhibitions in Munich.

In a statement, Berlin State Museums says that it is aware of the moral and ethical responsibility that Barbara Göpel’s bequest carries. A comprehensive check of the works shows that many of them were acquired directly from the Beckmann. The institution adds that it is “committed to further careful provenance research and a critical approach in accordance with the Washington Principles”—the international guidelines on handling Nazi-looted art in public collections.

In 1944, Göpel travelled to the Netherlands and Belgium on an art shopping spree with Hildebrand Gurlitt, the dealer whose collection caused a worldwide media sensation when it was discovered in the Munich apartment of his son Cornelius Gurlitt in November 2013. During their business trip they visited Beckmann, who was living in Amsterdam in exile with his wife Quappi. As a victim of Joseph Goebbels’s campaign against Modern art, Beckmann had left Germany the day before the Degenerate Art exhibition opened in Munich in 1937.

Beckmann lived in great insecurity because the market for his art had collapsed and, even at the age of 60, the threat of war service loomed over him. Göpel twice saved Beckmann from the draft, and the artist had shown his gratitude by giving him works. It is likely that Beckmann either sold or gave Göpel the two paintings that feature in his widow’s bequest during one of these visits.

The drawings in the bequest include scenes from Beckmann’s frontline service during the First World War, self-portraits, and portraits of Quappi and of the art dealer Gottlieb Friedrich Reber, many of which are studies for well-known paintings, the Berlin State Museums says.

The works will be included in an upcoming joint exhibition between the Nationalgalerie and the Kupferstichkabinett that focusses on the life of Göpel.