Painting takes time. This is the big theme of Laura Owens’s tremendous mid-career survey at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York. A set of 54 small clock paintings Owens made in 2011 and 2012 is the first sight visitors get when they step out of the elevator doors directly into the fifth-floor show. Many of the pictures, hung high atop a gallery wall, have gears and hands that spin at seemingly random speeds. What time could these paintings possibly be marking out? None of these abstract works, most of which are covered in swirls and daubs of garish, clashing colours, have clear minute or hour markers. It is as if they set their own tempo, warning us that this show will upset our standard pace of looking.

The clock pictures installation is a clever bookend. It is the first and last series in the exhibition, which includes around 60 works made over the past 20 years. Throughout that time, Owens, who lives and works in Los Angeles, had consistently rattled preconceived ideas of how to see a painting. Again and again, she has not only forced an expansion of taste by making “ugly” paintings, she has also made pictures that demand attention to the ticking clock hidden inside every work.

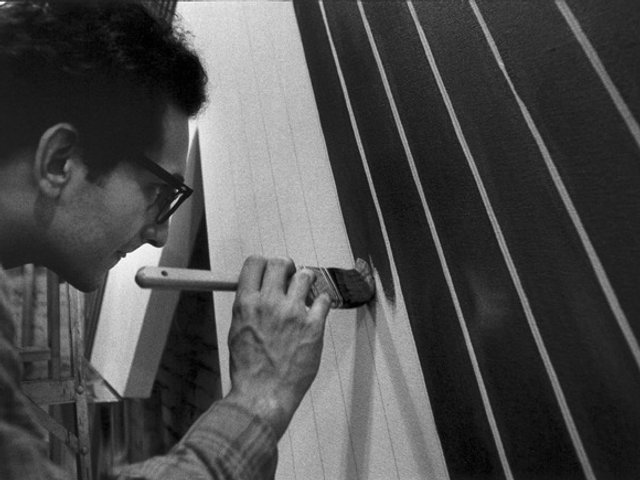

Early in her career, Owens realised she was interested in paintings about painting. For a student in Los Angeles (she graduated from the California Institute of the Arts in 1994), it was a curious enthusiasm. Long after most of her West Coast peers and teachers had given up on the theme, Owens was making pictures of pictures, as in a work from 1997 that shows two paintings hanging on a gallery wall at oblique angles. They are largely obscured through a truncated perspective, but the original version of one of the paintings depicted—a dark still-life of a bright lamp hovering over a wooden table with flowers—hangs nearby at the Whitney, reminding us of Owens’s kaleidoscopic sensibility, wherein one work is often refracted through another. (That awareness is echoes in the show’s inventive catalogue, which includes oral histories of Owens’s work through the voices of artists, writers and friends such as Chris Ofili, Rachel Kushner and Paul Schimmel. The cover of each catalogue is a unique screen print made in the artist’s studio.)

Laura Owens, Untitled (1997) Laura Owens. Collection of Mima and César Reyes

Owens is at her best in this self-reflexive register. She is good at giving us pause and herding us back to pictures for a second look. Her best paintings open doors into one another. But she falters in works that are less self-aware, and that try too hard to make a virtue of her otherwise compelling peculiarities. Because she is so good at convincing us to adapt our registers to her own, she can sometimes transform an otherwise frivolous theme—like, say, a cartoonish leopard sitting in a tree, cleaning its paws with its tongue—into a vehicle for testing how far she can push against prevailing good taste. Such pictures are unforgiving on the eyes at first, but they ripen upon repeated viewing. The 2006 leopard painting (all of Owens’s works are untitled) does this succinctly, which many other figurative works made between 2003 and 2011 (they hang together in one gallery), largely fail to do.

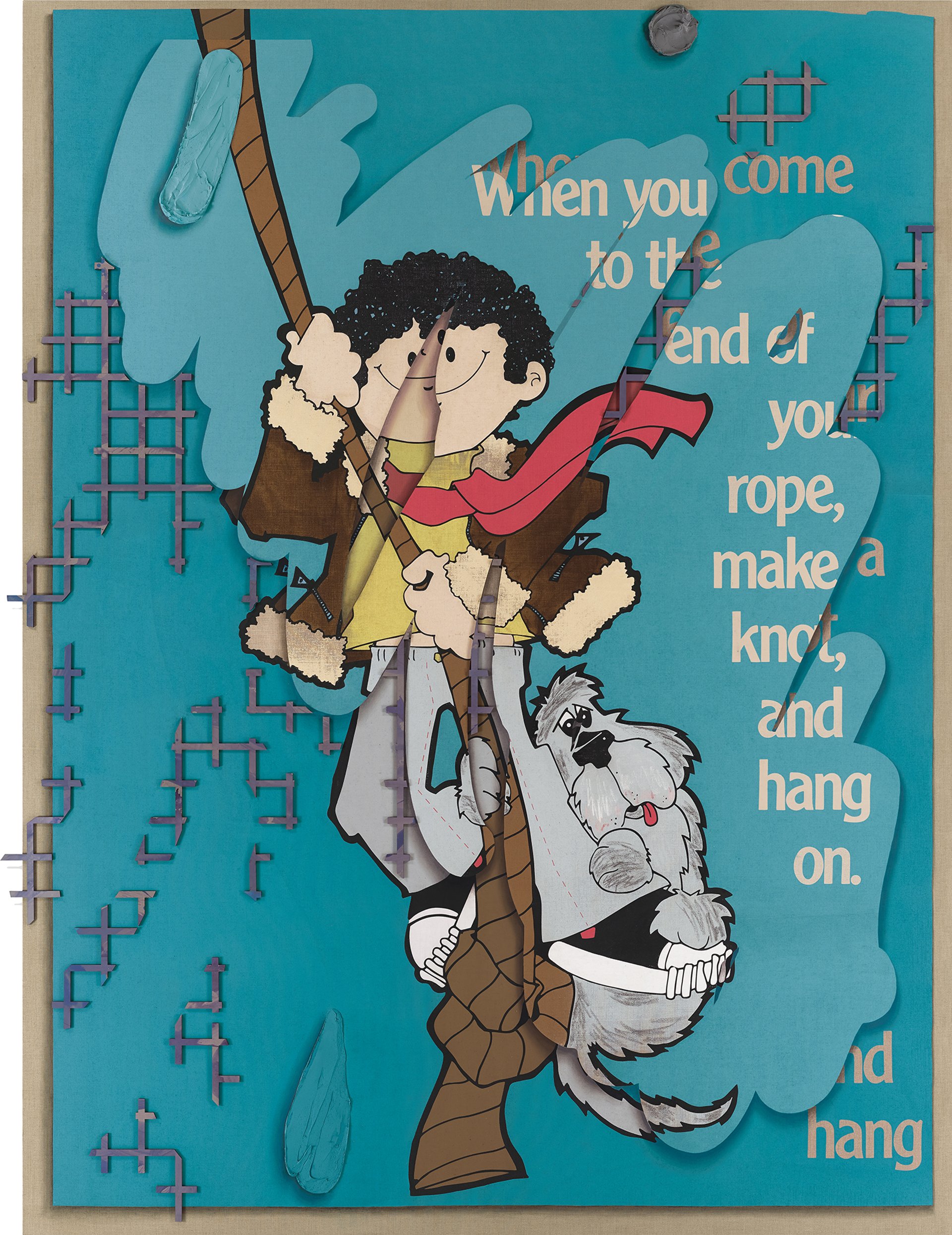

Since that relatively fallow period, Owens has gone from strength to strength. In her most recent and best works, such as a picture from 2014 of a cartoon boy and his grey dog dangling from a rope, she has discovered how to press her figurative sensibility in line with her vision for abstraction. Parts of the painting are covered in a lattice grid (one of her signature marks) that remind us of the flatness of the picture plane, which Owens has nevertheless filled with an enormous amount of space. This is a work of many layers, which she has enriched with recessive shadows, curious spatial openings and a sense of good cheer about painting that so few others know how to handle.

Laura Owens, Untitled (2014) Laura Owens. Courtesy of Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

The picture of the boy and his dog is relatively easy to like. It does not demand the time that so many of Owens’s other works do. It is, on the whole, something of an anomaly in this splendid exhibition, which proves, above all, that we cannot see paintings all at once. It takes time to make a good picture—and it takes time to see one too.

• Laura Owens, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, until 4 February