With museums hosting a growing number of highly immersive, thoroughly hyped and exceedingly popular art installations, it was probably inevitable that some institution someday would limit visitor interaction with a work to a matter of seconds.

That day has come with Yayoi Kusama’s travelling Infinity Mirrors exhibition, where museum staffers at different venues have been moving visitors along after a brief sneeze of time—only 30 seconds per visitor per room—or roughly as long as it takes to power up an iPhone.

It makes the one-minute time slot offered to see Kusama’s newest piece at David Zwirner gallery in New York seem oddly generous, and the 10 or 20 minutes that other museums allot for installations such as Doug Wheeler’s noise-cancelling PSAD: Synthetic Desert III (1971) show at the Guggenheim earlier this year, feel positively abundant.

As you can imagine, the 30-second rule has upset some Kusama fans on Instagram, who complain that it is not even enough time to take a selfie. But there is another problem with the time restriction, as I discovered when visiting the Infinity Mirrors show at The Broad museum in Los Angeles, the third venue on a six-city tour starting at the Hirshhorn Museum in Washington, DC, where the 30-second rule began.

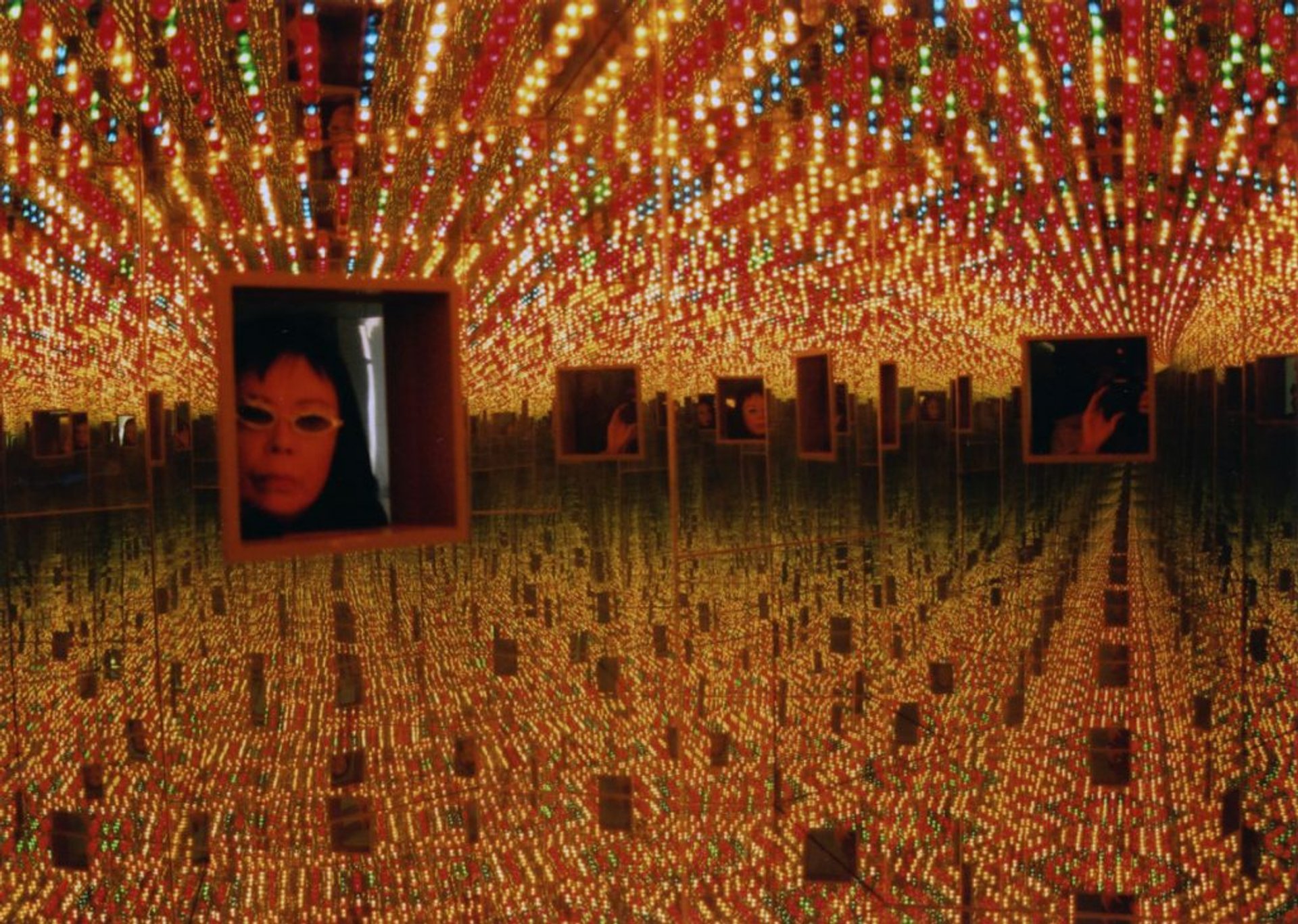

Yayoi Kusama inside her Infinity Mirror Room—Phalli’s Field (1965), at Castellane Gallery, New York Yayoi Kusama; Courtesy of Ota Fine Arts, Tokyo/Singapore; Victoria Miro, London; David Zwirner, New York

It turns out that half a minute is not enough time to experience the most powerful dynamic of these rooms: our shifting perceptions of what is far versus near, or personal versus universal, as one collapses into the other through the unending regression of mirrored images.

As Kusama has long discussed, the Infinity Mirrored Rooms have a disintegrating effect, taking something known to be solid, like our own face or a pumpkin, and distributing it across the visual universe like so many stars in a galaxy. “The Earth is only one polka dot among a million stars in the cosmos,” she has written. She has also framed these works more personally in terms of “self-obliteration”, the disintegration of the individual ego and the spreading of love into the universe.

In effect, Kusama has shattered classic expectations of contemplating a work of art into so many glinting shards. Sure, we can try to fix our vision on a particular object, but we find our focus bouncing off a dazzling sea of self-repeating images and flashing lights. We seek the foreground and find everything has disintegrated into the background. While each Infinity Mirrored Room has its own colours and special effects, all deflect our attempts to find a single focus or horizon line, overwhelming us with a kaleidoscopic vision.

But the push and pull of this near-is-far and I-am-everywhere dynamic, or simply the focusing and refocusing of your vision, takes some time. And 30 seconds is hardly long enough to spot images of yourself or your friend in the installations (many are designed to accommodate two visitors), let alone to begin to follow the electric polka-dotted trails to infinity.

On the drive home from The Broad, I kept thinking that Infinity Mirrors has to be the most misleading exhibition title ever: the show whips up the anxiety of running out of time instead of offering the illusion of endless anything. This exhibition felt like a tease for another exhibition. Above all it was frustrating: a peep show for museum-goers.

Peering in to Yayoi Kusama's Infinity Mirrored Room—Love Forever (1966/1994), at Fuji Television Gallery Yayoi Kusama; Collection of Ota Fine Arts

Granted, Kusama herself was inspired by the mechanics of voyeurism. As early as 1966, for Kusama’s Peep Show at the Castellane Gallery, she created a light-studded, mirror-lined hexagonal box that worked like a Times Square viewing booth (minus the coin-operated machine). A newer version of that chamber is currently on display at The Broad, as is the one from 2007 that is part of Dots Obsessions—Love Transformed into Dots.

These two works, which you do not enter but peer into, are the strongest and in many ways the most honest works in the show. Here at least, the idea of teasing the viewer is built into the very nature of the installations, designed to deliver by withholding.

The other works are just glimpses of what a more meaningful experience might look like. You might remember that 30 seconds is, according to the most robust studies in the field, around the average time a visitor typically spends looking at a work of art in museums.

You might also remember that museum professionals often cite this brief window of time as an example of either a failure on their part to engage visitors, or on the visitors’ part to slow down and connect with the art. The fact that visitors tend to spend just 30 seconds in front of a masterpiece at the Met is widely taken as a sign of our hyper-accelerated, ADHD times.

So what does it mean that other museums, like The Broad and the Hirshhorn, are now deliberately choosing to turn their visitors into inattentive viewers?

Yayoi Kusama, Infinity Mirrored Room—The Souls of Millions of Light Years Away (2013) The Broad collection, Los Angeles

The museums both say that Kusama herself routinely establishes time guidelines to make her installations accessible to more people, and the Hirshhorn publicist added that the artist “worked closely” with curators there to establish the 30-second rule for the show. But the museums’ ambitions to draw the biggest possible crowds clearly figure into the equation as well. The Hirshhorn brought a record 160,000 people through the museum doors during its run, and the Broad has sold 90,000 tickets at $25 each, selling out the first batch of 50,000 within a single afternoon. (One Los Angeles Times headline questioned if the show was “Hotter than Hamilton?”)

This calculus that values quantity of visitors over quality of experience is understandable but unfortunate. Even 60 seconds per room would allow a more substantial experience, as it has for me in the past with the one Infinity Mirrored Room in The Broad’s permanent collection.

Instead, the Hirshhorn, The Broad and other venues have essentially decided to give twice as many people half as much art, with what you might call infinitely diminished returns.