The Vietnam Veterans Memorial opened on the National Mall in Washington, DC on 13 November, 1982. The main structure is an angled wall of black marble, built beneath ground level and inscribed with the names of Americans who died in the Vietnam War, a conflict that divided the country.

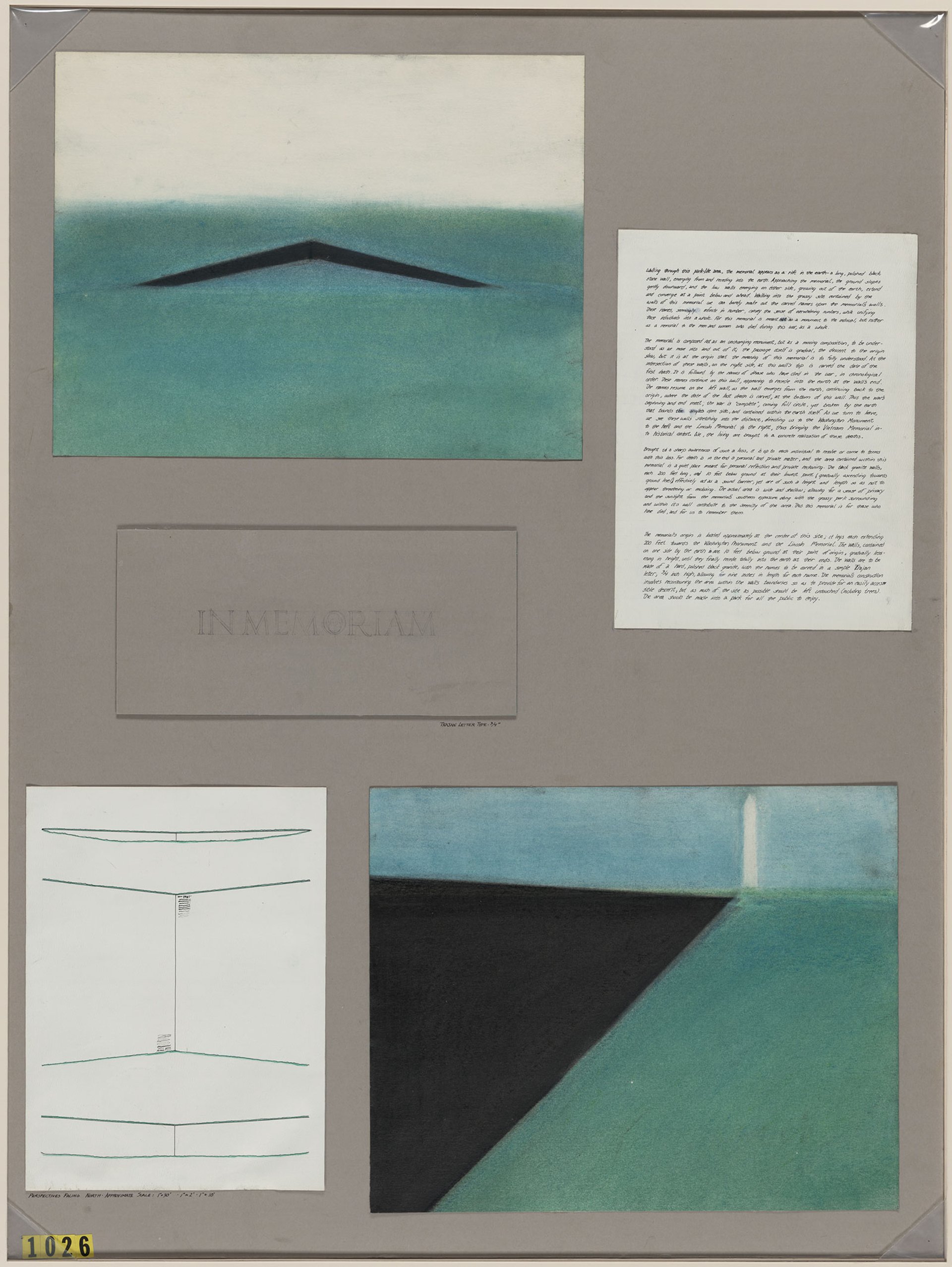

The memorial was similarly controversial at first. It was designed by Maya Lin, who was a Yale student, aged 20, when she submitted the proposal to a national competition. Her original plan had a series slabs inscribed with names leading to the site’svertex, evoking the notorious “domino theory” of Communist expansion that some American leaders cited to justify US involvement in Vietnam.

But even without the domino-theme, Lin’s wall fueled bitter opposition from some veterans and from politicians before and during its construction, which cost $8.4m and was paid for through private funding. Critics attacked that plan for its abstract shape, dark colour, descent below ground level, absence of patriotic symbols, and for the fact that the US-born Lin was of Asian descent.

Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund

Eventually a compromise resulted in the commissioning of a classical bronze statue of three soldiers that is installed across an expanse of grass from the black wall. A Vietnam Women’s Memorial nearby shows three servicewomen with a wounded trooper.

Overnight, veterans accepted Lin’s wall as a solemn monument, and over time critics lost their forum. Today, the memorial is visited by more than 3 million visitors every year. Veterans and their families can be seen at all hours on the path that runs along the wall of inscriptions, taking paper and rubbing a crayon or pencil over the names of dead soldiers for keepsakes.

In his recent book A Rift in the Earth: Art, Memory and the Fight for a Vietnam War Memorial, James Reston Jr revisits the battle over the official monument in Washington to the unpopular war. He tracks the struggle to finance the project, and includes some of the many designs that were submitted to the open competition. Reston discussed the unexpected success of the wall, and the ongoing controversies over monuments in the US, in an interview with The Art Newspaper.

The guidelines for the design of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial specified that the monument not be political. Is that a realistic guideline for any historical monument?

There were 1421 submissions. They are absolutely remarkable to go through in the Library of Congress. How artists tried to navigate that line of being effective without being political was quite fascinating. The design proposal that Maya Lin made in her class at Yale was intensely political. She has yet to be grateful to that class for adjusting that design. The row of dominoes was intensely metaphorical. It was an anti-war, anti-Vietnam statement. By eliminating that, she achieved apoliticality.

How has the memorial’s meaning evolved in the last few decades?

Part of the magic of that thing today is how it’s become universalised. It began as a veterans’ memorial. It’s no longer a veterans’ memorial. It began for the warriors and the survivors. It’s become much more than that in the decades since it’s been built. The tourists from all over the world who come to see it don’t come to ponder the Battle of Pleiku or the fall of Saigon. That memorial is now for all wars, not just the Vietnam War. It’s not just for veterans. It’s for the entire Vietnam generation, for pacifists just as much as for warriors. What it represents is the cost of war, and that’s what the soldiers are looking at, but it’s a universal theme now.

You may have seen young fathers with strollers visit it. That’s a common sight. What fathers in their 20s, 30s and 40s say to their children is not about the specifics of the Vietnam War any more. That’s the extraordinary accomplishment of a single work of art. The emotional response has transcended Vietnam, and that’s the bonus that no one could have anticipated, certainly not Maya Lin.

The emotional response has transcended Vietnam, and that’s the bonus that no one could have anticipated, certainly not Maya Lin

Did the memorial’s surprisingly unifying design quash the critics? Does good design nullify the naysayers?

It has with time, but not during the art war that happened within those five years. It was about as divisive as you could possibly get. All those things—that it was below ground, it was like a great privy, it was black in colour, there was no flag, there was no inscription for glorious service and courage—but even the most virulent detractors of her design came around to it when they saw the reaction to it.

I gave [the leading opponent of the design, Virginia Senator James] Webb the chance to say something graceful about how he had changed his mind about the whole thing, but he wouldn’t talk to me.

Critics tried to “fix” Maya Lin’s design with an American flag and other statues. How do you feel about “fixing” memorials to Confederate heroes, instead of simply removing them? Should memorials be updated?

I’m just back from Atlanta and a discussion about Confederate statues at Stone Mountain, which is often the place where the Ku Klux Klan gathers. There’s a debate over whether those statues should be removed. It really is a question of where you draw the line and what use is made of these statues. Whenever a Confederate statue becomes a gathering place for Nazis, it’s a real problem. But the idea of expunging entirely the history of the American Civil War and casting the cloak of shame on all things Confederate, I think, is going too far.

You’ve written about the idea that multiple parties could be represented in monuments. Could new guidelines for the design of memorials include multiple opinions, or is that a minefield, too?

A friend of mine, a prominent lawyer in Atlanta, had the notion that if Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson are at the base of Stone Mountain [honouring Confederate leaders], you really ought to put a statue of Martin Luther King on the top.