The US artist Oscar Tuazon connects the functional possibilities of sculpture to the politics of public art, exploring the confrontation between industry and ecology, the urban and the natural. Two events this year represented a clear synthesis of the various ideas Tuazon has developed in his work over the past decade. In April, he opened the gates to the yard next to his Los Angeles studio and hosted a hip-hop concert by musicians he had met several months earlier at Standing Rock, a camp set up in North Dakota by protesters against the Dakota Access Pipeline. By the entrance, he placed a section of pipe six feet in diameter, part of a previous work. A cast iron sculpture was filled with wood and lit, making an improvised fire pit, and a stage was built for performers.

Around the same time, Tuazon was completing his sculpture Burn the Formwork, which was unveiled at Skulptur Projekte Münster in June. The concrete structure—perhaps the most celebrated work of Tuazon’s career—combines the interactivity of a stage with the comfort of a fireplace. The artist has also been converting a building in the far north-west of Washington state into a rural home.

The Art Newspaper: Tell us about your cabin in the woods.

Oscar Tuazon: It’s on the Hoh River, a very protected river in the Olympic Peninsula, about four hours from Seattle. It feels like the end of the Earth. When my wife Dorothée got it, six years ago, the house was a big shed. Whoever was building it died before doing anything to the interior. There was no road to the house, no electricity, no water. It’s in a region where it rains 300 days a year, and it’s right next to a river, but the previous owner had drilled a well and come up with nothing. So we installed a rainwater collection system. Now it’s habitable, but it’s still basically a big shed.

Is the house a work?

Well, it isn’t really—it’s a house. But it might become a work at a certain point. For me, a house is the ultimate sculpture. I think of trying to solve those problems of living as a sculptural process. Installing the water system was a big revelation for me. But I haven’t shown it so I don’t know if it’s a work yet.

Photo: Henning Rogge; © Skulptur Projekte 2017

Is that what makes a work?

Yes, it is, kind of. The act of seeing is what completes the work. The moment when a work is given over to the public is really just the beginning. My work for Skulptur Projekte Münster was maybe the most amazing experience of that that I’ve ever had. When I opened the barrier around the sculpture, it was late at night. A couple of wandering ravers stopped by and, without speaking, they immediately started putting wood in the fire. It was euphoric, to feel that the work now belonged to someone else.

The moment a work is given over to the public is really just the beginning

The confrontation that happens in public art is so unpredictable. You think you’ve imagined everything that could happen, and there’s always a surprise. I designed the structure to be impervious to fire. It has a powerful rocket stove and an internal combustion system that burns really hot, with almost no smoke. That part is built out of refractory cement, which can withstand enormous heat. But, of course, people started a fire outside the stove, just on the floor in front of it. The chimney itself is made of normal concrete, and that area burned and started to crumble, so it had to be repaired.

Is there a difference between a straightforwardly functional work, like a fire pit or the stage in your yard, for example, and a sculpture that the public completes, as you say, through interaction?

There’s space for both. Especially in Münster, there are many times when a piece recedes into the background. I think that’s when it’s most successful, when it disappears as sculpture and facilitates some other kind of activity.

How do those aspirations map on to your work in galleries?

For a long time, I thought that was inherently impossible in a gallery setting, because the gallery has already solved all the problems of function. But recently, I’ve started to think more pragmatically that the exhibition space is just the beginning of the work that can be done; it can facilitate the production of an object, but the object has to keep moving.

Stefan Altenburger Photography

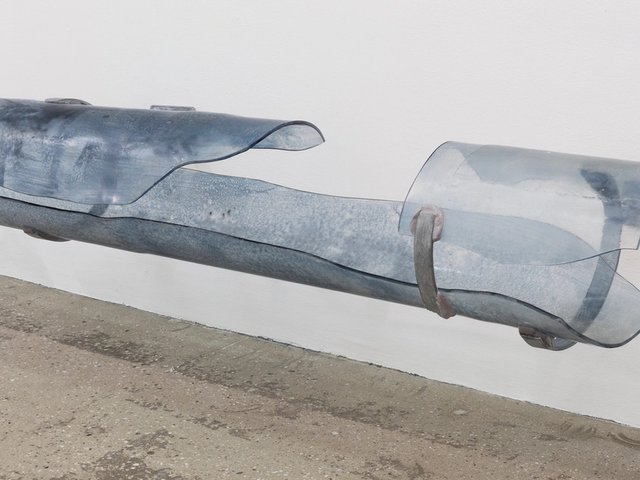

How does that relate to See Through, your recent exhibition of window sculptures at Galerie Eva Presenhuber, Zurich?

I’ve done two shows now at Presenhuber based on this idea of the 1:1 model. I set out just to prototype a new set of windows for my house. But other things happen along the road. With these double-pane windows, I got stuck in that space between the glass. It’s a space of reflection, literally. Texts and images and materials started accumulating there. It’s like the space between the walls—an unseen and uninhabitable part of architecture.

It seems that many of the ideas in your work correspond to natural forces and phenomena.

Yes, it all comes back to trees. It comes back to the idea of the tree as a person, but also the tree as embodied water and embodied sun. It is both a living and a non-living material. I’ve been trying to make an artificial tree for years.

Why, then, do natural materials so rarely feature in your work?

I would say that the construction of an object should be a way to make natural forces visible. I recently developed a proposal for a submerged plinth in the Port of Sydney. I asked myself, what is there? There’s the sun, the wind and the water. What I proposed was a huge weather wheel, with a wind turbine in the centre powering an outer water wheel, creating a cloud on some days, maybe nothing on others. It would be a way of seeing weather. I think works can play a really interesting role in the conversation around ecology because they are little systems, and you can model an ecology in an artwork.

I think works can play a really interesting role in the conversation around ecology

© Art Basel

Does that happen elsewhere in your work?

I’m working on a project based on the Zome, one of the first modern passive solar houses. It was built in New Mexico by Steve Baer in 1971-72. The façade is barrels of water, which absorb heat during the day and then warm the house during the night. I reproduced its structural shell, which I titled Zome Alloy and showed at Art Basel in 2016. The house is very didactic. To me, ideally it should be a public space: it should be a school or a laboratory. I don’t just want to make a replica, though; I want to update it.

What took you to Standing Rock?

I grew up on Suquamish land near the Port Madison reservation in Washington state, and in my teens, I studied the Lushootseed language. I haven’t been so deeply involved in politics, but this issue [Native American water rights] was something that really spoke to me; it was very clear that something should be done. I think about the camp at Standing Rock as this laboratory of architecture, combining traditional forms with improvisation and technology. It was amazing. Every object had a function—there was a total economy of purpose.

After Standing Rock, I made a couple of tent structures. One [was] in an exhibition at the Contemporary Art Museum in St Louis [Urban Planning: Art and the City 1967-2017]. The idea is to donate that sculpture to the horse riders who are protesting along Line 3 [a section of oil pipeline that has prompted Native American protests]. I want to make an object multifunctional, so that it could actually slip between these contexts.

I’m so used to having things that engage in the space of art. To make something function outside that is challenging—to get it to function in an authentic way, to actually be useful.

• Click here to download a PDF of The Art Newspaper's Sculpture 2017 magazine, supported by Momart