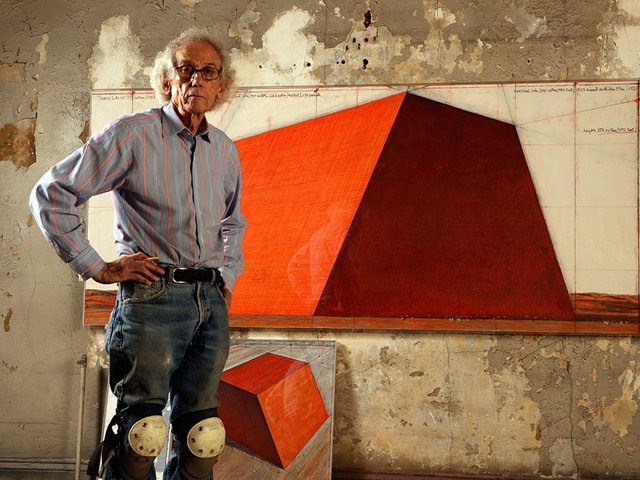

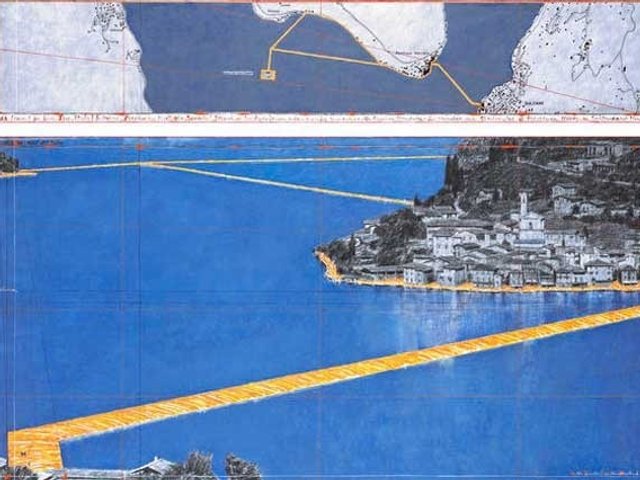

Earlier this year, Lorenzo Quinn became the first artist to install a work of art directly into the waters of the Grand Canal in Venice. Next year he plans to take on another watery site: Lake Iseo in northern Italy, made famous in 2016 by Christo’s Floating Piers, an installation of three kilometres of dahlia yellow fabric that formed a bridge to Monte Isola.

“I was blessed with Venice, we had the backing there,” says Quinn, the son of the Oscar-winning actor Anthony Quinn. “They have just asked me to take over the lake site where Christo created his work last year.”

Still in the early stages, Quinn says the proposed monumental steel installation, titled You Are The World, refers to temporality and the fleeting nature of life. “It’s about the passage of humans on earth. Nothing is forever; now is our time to leave a mark,” he says. The artist says he wants to get children involved in creating the sculpture.

Climate change is the subject of much of Quinn’s work, including several new pieces in his exhibition that opened at Halcyon Gallery in London this week (until 22 December). Support, which was installed to coincide with the Venice Biennale, emerges from the Grand Canal and appears to prop up the walls of the historic Ca’ Sagredo Hotel.

It is a call to politicians around the world to take action before it’s too late, Quinn says. The work has proved so popular with the public its run has been extended from November until next spring, the Telegraph reports.

Christo’s Floating Piers also brought unprecedented attention to the small town of Sulzano on the shore of Lake Iseo. The three kilometres of fabric walkways attracted 1.5 million visitors over just 15 days. After its stint in northern Italy, the 45-tonne work was shredded and turned into insulation.

Installing Christo’s work was a mammoth undertaking that involved divers sinking 160 anchors, each weighing five tonnes, into the bed of Lake Iseo. It is a process Quinn is familiar with.

“When we went to install Support in the Grand Canal there were unusually high tides,” he says. “We were able to place one hand, but the second hand just wouldn’t fit. That night we had a critical meeting, but when we came down at 7am the next morning, miraculously the tide had gone down and the hand had set into its base overnight.”