In Human Flow, Ai Weiwei’s debut as a film director, the Chinese artist-activist offers his own testimony on the global refugee crisis. His documentary mixes the epic and the personal, in the hope that his involvement will bring attention to an intractable problem.

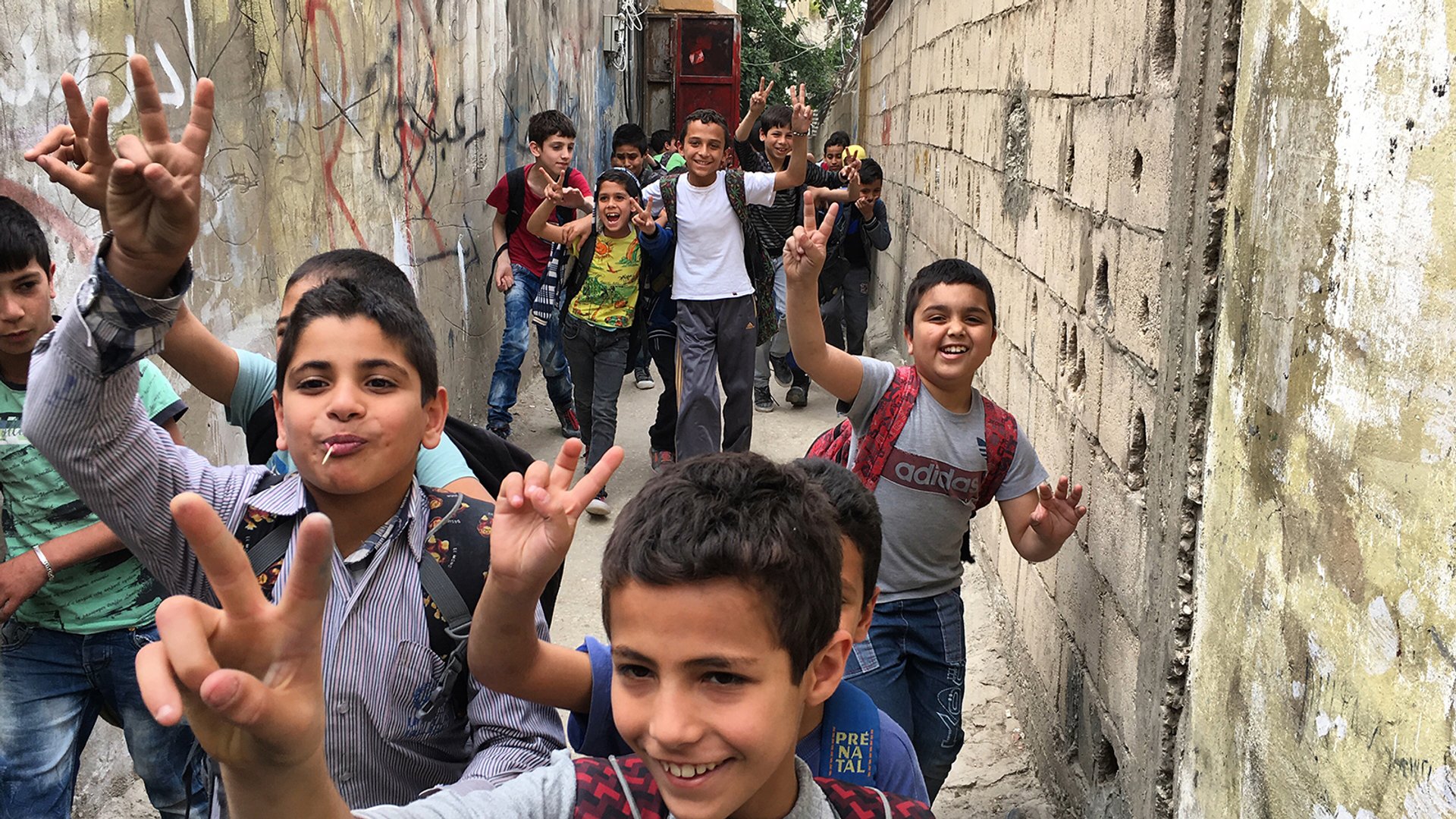

More of a journey than a j’accuse, Human Flow is a new medium for Ai Wewei—the feature film—yet the artist is also working with a medium that he has deployed for year—himself. He is leveraging his own presence to move officials to act, whether on the Greek island of Lesvos, in the barren walled-in Gaza Strip, or in ships on the Mediterranean.

His film deploys paradoxes. The man who was banned for years from travelling and was put under house arrest by Chinese authorities is now journeying to camps around the world and deploring the homelessness of millions. The film’s title, Human Flow, evokes a flood of undifferentiated humanity, yet Ai Weiwei joins the columns of migrants to interview refugees as individuals.

There are also some visual flourishes. Drones hover high above sprawling refugee camps, where figures move in fast motion like digital signals, closing in to stress the human factor in the human flow. In Kenya, a huge refugee population is shrouded in clouds of dust. We’re left with Sisyphean perpetual motion, but never in a single direction and never toward a permanent home.

The artist has put his signature wit on hold in most of Human Flow, as he did in 2008 when he condemned official inaction after more than 5,000 Chinese children died when schools collapsed in an earthquake in the Sichuan region.

Photo courtesy of Amazon Studios

Yet a memorable scene in Human Flow offers a clever fable. In Gaza City, a place of managed refugee squalor walled off from the outside, a tiger thought to have entered by tunnel from the Sinai is stranded. With logistical pyrotechnics, the animal is packed into a shipping container and airlifted to South Africa. Ai Weiwei leaves us to wonder about all the humans left behind.

The documentary joins a flow of films about refugees, such as Gianfranco Rosi’s Fire at Sea, about African migrants on and around the island of Lampedusa, which won an Oscar in 2015, and Sea Sorrow, the actress Vanessa Redgrave’s directorial debut, which is now touring festivals. Even with Ai Weiwei as the Al Gore of the refugee crisis, the documentary is likely to be more of a fundraiser than a crowd-pleaser in a marketplace saturated with cries de coeur.

And, like most documentaries, it has already been overtaken by events like the rise of the German right-wing anti-refugee political party Alternativ fur Deutschland and the current flight of Puerto Rican hurricane victims to the US mainland. Still, the inconvenient truth remains the same. The columns and camps of refugees that Ai Weiwei’s camera observes, from near and far, keep growing.