The recent debate about problematic public sculpture is spilling over into Frieze London. While the US grapples with what to do with its Confederate monuments, and the repercussions of the installation in Minneapolis earlier this year of Sam Durant’s sculpture Scaffold (2012), an evocation of Native American executions, continue to play out, it is Angola’s controversial memorials that interest Kiluanji Kia Henda, the winner of this year’s Frieze Artist Award. Kia Henda is one of seven artists and artist collectives showing new commissions in the Frieze Projects section at Frieze London, organised by the curator Raphael Gygax from Zurich’s Migros Museum für Gegenwartskunst.

“I think of [colonial] statues as clandestine citizens; their visa has expired and they need to be deported,” says Kia Henda, the 2012 recipient of Angola’s National Culture and Arts Award. “Or, even better, we should exchange them for African sculptures that were stolen during colonisation.” His multidisciplinary commission for Frieze centres on a bust of Vladimir Lenin that once stood in Angola’s main square; the artist has reimagined it as a witchcraft talisman, impaled with nails.

The Art Newspaper: Your Frieze commission is ominously titled Under the Silent Eye of Lenin. What is it about?

Kiluanji Kia Henda: It is a project I have been working on for a year that is based on Angola’s Communist past. The Frieze commission is an installation that includes three sculptures, a series of 20 silkscreen prints and a video. The title comes from Angola’s [then] new president António Agostinho Neto’s first speech after the country’s independence in 1975, [which took place] near a public sculpture of Lenin. I found the phrase interesting because it had a spiritual dimension and the presence of the bust made me think of a kind of idolatry, which is paradoxical given that Communism rejects the doctrine of religion.

David Owens

The work also draws on myth and science fiction. How do these fit into the Communist history of Angola?

I’m not a historian, I’m an artist, so I like to mix up some of the past with fiction. In times of extreme violence, fictitious things become important and we use them as a resource to protect ourselves from our fears. There is a parallel to how, during the wars in Angola, soldiers in the bush used witchcraft, and during the Cold War, the US and the Soviet Union used the narrative of science fiction to seem invincible. It was about having supernatural powers.

For my Frieze Project, I worked with artisans in Luanda who make fake Nkisi sculptures, which are thought to have spiritual power and are used in witchcraft. Original Nkisi used in rituals are rare and have become expensive, so new ones are buried for months to make them look older so they can be sold in the markets. I commissioned three wooden busts of Lenin. The first is on a plinth, facing a video I’ve produced on making the Nkisi with a voiceover of someone speaking in Russian as though they were Lenin about his presence in Angola; the second is partially buried in red sand. The third is the final Nkisi, which was buried for a month so it looks like an old piece; it has nails driven into it and is covered in a black translucent veil. It’s in its own room and is like an altar—a shrine to Communism.

Recent controversies show that we are still unsure of how to deal with problematic monuments. How do you handle these?

For my [ongoing] photo and video series Homem Novo (new man, begun in 2010), I used the empty plinths left behind after colonial statues were removed following [Angolan] independence and invited people to stand in their place. I wanted to celebrate a new generation of artists that had flourished after the [civil] war ended in 2002—to replace war heroes with cultural heroes. I think that’s how the plinths in a city should work. They shouldn’t be static things.

You are the first African artist to win the Frieze Artist Award. There has been a lot of growth in the contemporary African art market recently—what is driving this interest?

Curators such as Okwui Enwezor and Simon Njami, along with African artists, have been working hard for years to promote African art. For a long time, there was a lot of ignorance about the continent because of a lack of access. Now, people are starting to realise that many of the narratives in African artists’ work are surprisingly contemporary. Western institutions have become more open but the answer to increasing the popularity of African art comes from inside. In Angola, we still do not have a museum of contemporary art, but [our national pavilion] won a Golden Lion in Venice in 2013. There’s still a lot of homework to be done, but it needs to happen on the continent.

• Frieze London Talk: Alt-Monuments (Jeremy Deller, Antony Gormley, Adam Pendleton and the curator Ralph Rugoff), Friday 6 October, 12.30pm

Other Frieze Projects

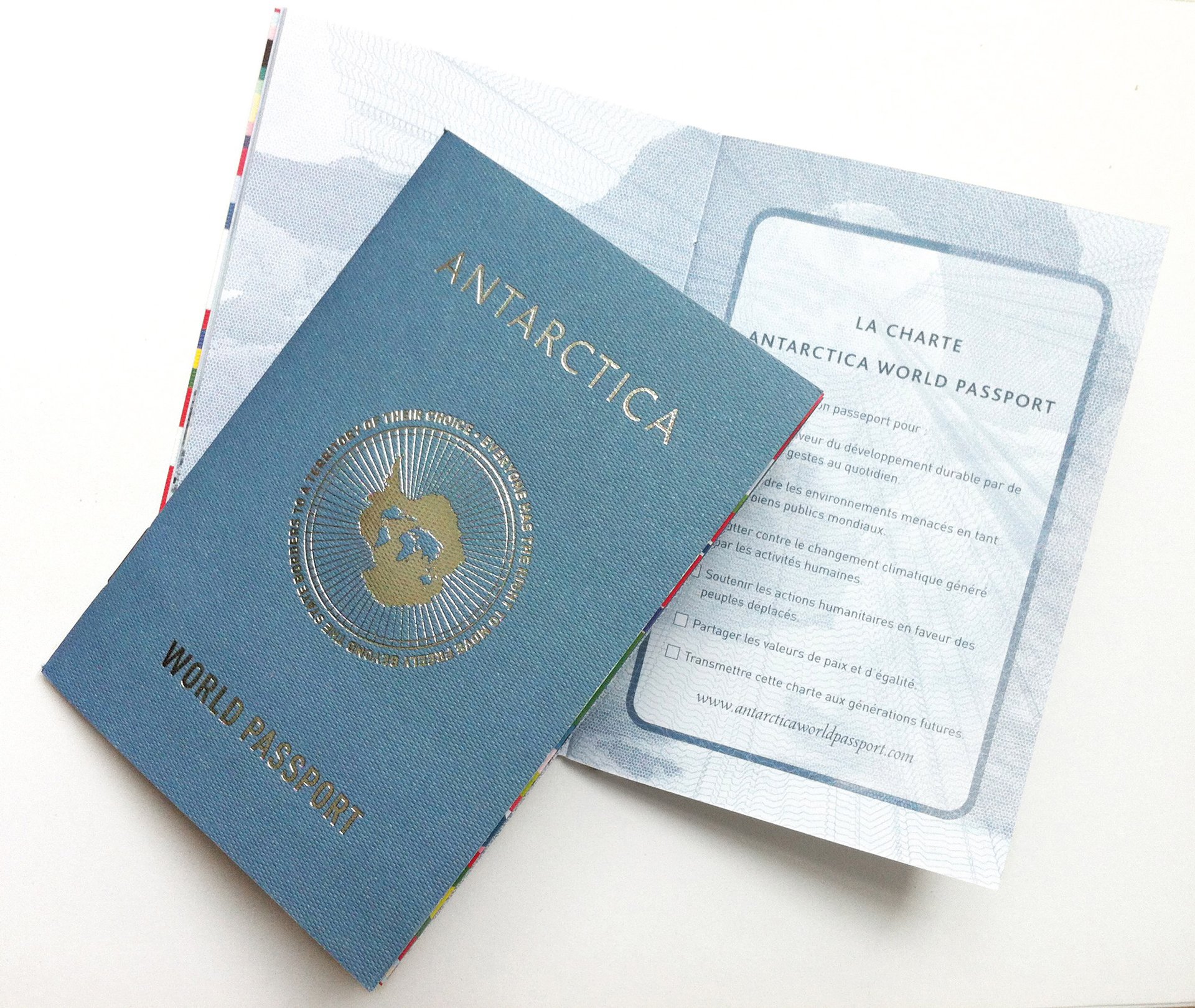

courtesy of Lucy + Jorge Orta

Lucy and Jorge Orta

Antarctica World Passport Office

First presented at the 46th Venice Biennale in 1995, the Antarctica project by this British-Argentine artist duo was inspired by the Antarctic Treaty, which declares that the icy continent is “a natural reserve, devoted to peace and science”. At Frieze London, 5,000 specially-made passports inviting participants to become “world citizens” are available at several stands throughout the fair. By accepting the passports, visitors declare their collective support for international issues such as the refugee crisis and the fight against global warming.

Moon Kyungwon and Jeon Joonho

Freedom Village

Scattered across Frieze London is a project about a Korean village that has been hidden from the world for more than six decades. Taesung, known as the “Freedom Village”, is an isolated farming community in the demilitarised zone between North Korea and South Korea that came under UN jurisdiction at the end of the Korean War in 1953. Access to the area, which has 207 residents, is tightly controlled due to its strategic position. Photography and film by these South Korean artists aims to show how political ideology and conflict can dull life.

SPIT!

SPIT! Manifesto

The artists Carlos Motta, Carlos Maria Romero and John Arthur Peetz are making their debut as a collective at Frieze, calling themselves Sodomites, Perverts, Inverts, Together! (SPIT!). They are working with six performers to interpret self-written manifestos to create what they describe as “a crossover of queer activism, art and choreographic movements”. The first manifesto lists both derogatory and self-appropriated terms used to describe queer subjects and the second is a list of demands to the government related to sex and gender politics.