The US Supreme Court will determine whether US victims of a terrorist bombing in Jerusalem can seize antiquities on loan to a Chicago museum as recompense for their suffering.

The story begins in 1997, when Jenny Rubin and seven other US citizens were injured in an attack in the Israeli capital that killed five civilians. Although the attack was carried out by the Islamist group Hamas, Rubin and the other victims successfully argued in a US federal court in Washington, DC that Iran had funded the terrorists. In 2003, after Iran failed to defend the suit, the victims were granted a $71m judgment against the nation.

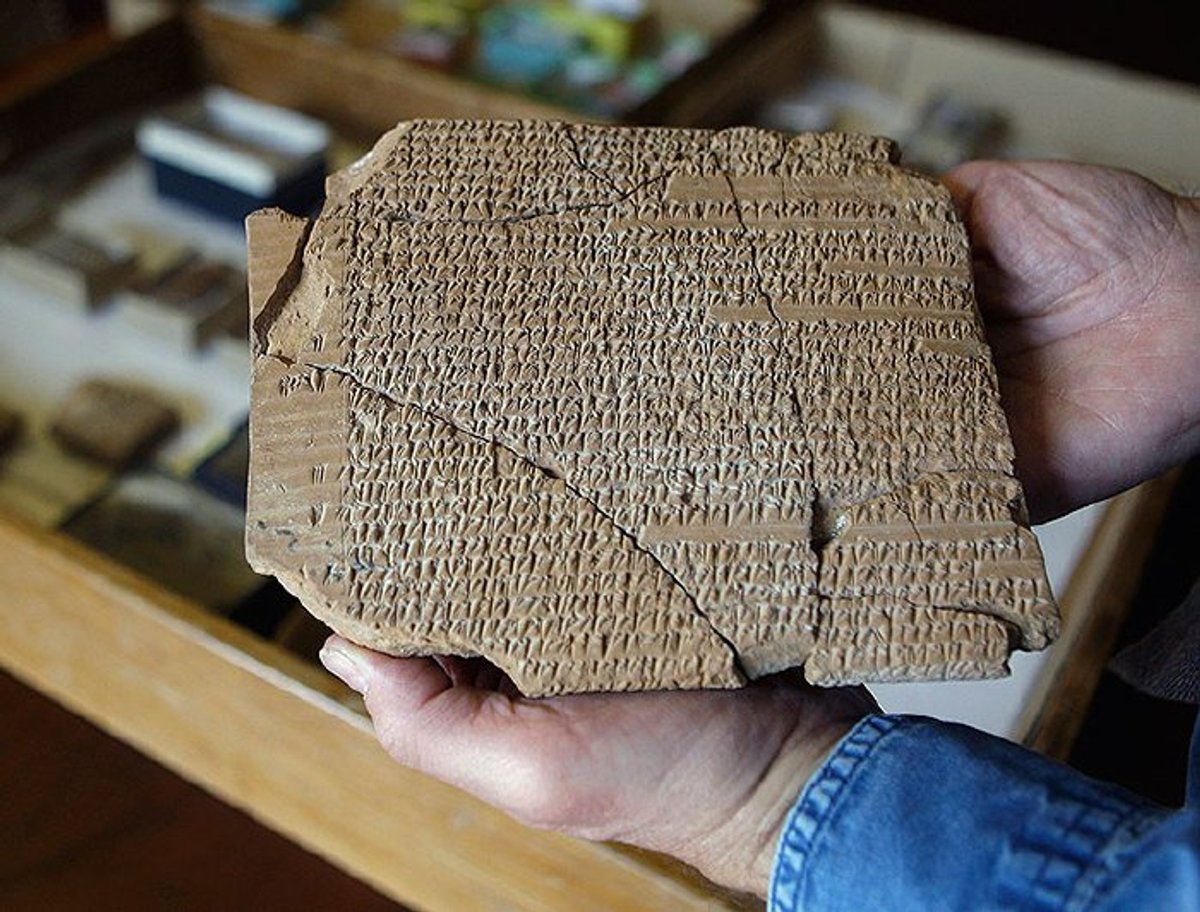

Soon afterwards, they sought to enforce the judgment by claiming Persian clay fragments and tablets on loan from Iran to the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago, together with antiquities at three other US museums.

Under a federal immunity law passed in 1976, foreign nations and their assets are generally immune from legal cases in the US, although an exception permits claims against nations that sponsor terrorism. However, this exception requires that the foreign state’s assets must be related to the US by “commercial activity” in order to be seized.

In 2016, a federal appeals court ruled that the victims could not seize the antiquities at the Oriental Institute in Chicago because Iran never used them in a commercial activity in the US.

The Supreme Court will now decide whether a 2008 change in the foreign immunity law gives the claimants the right to seize Iran’s assets anyway, without regard to the commercial activity test.

If the claimants are successful, the impact of the case “will be minimal”, says their lawyer, Asher Perlin. The terrorism exception applies only to designated state sponsors of terrorism—Iran, Syria and Sudan—and a typical case seeking to claim such a state’s assets in the US would not involve art, he said, but rather financial assets, real estate or tangible property. He says that US museums generally protect international art loans from seizure under a widely used US State Department immunity programme introduced in 1965. As the artefacts at the University of Chicago were brought into the US before the programme began, the protection does not apply to them, he says.

Jeremy Manier, a spokesman for the University of Chicago, tells The Art Newspaper that the ancient Persepolis artefacts have unique historical and cultural value and “are among the most important historical documents from ancient Persia. We will continue efforts to preserve and protect this cultural heritage,” he says.

The plaintiffs’ claims against the three other US museums have all been dismissed. A hearing on the case in the Supreme Court has been schedule for 4 December.