The National Gallery of Ireland is due to stage the first exhibition in more than a century on the life and work of Frederic Burton (1816-1900), reassessing the career of the gifted miniaturist and watercolourist who ran London’s National Gallery for 20 years but whose role in reshaping the institution has been often overlooked.

From 1874 to 1894, as the gallery’s third director, Burton oversaw the acquisition of more than 500 works, including Leonardo’s Virgin on the Rocks (1485), Botticelli’s Venus and Mars (around 1485) and Holbein’s The Ambassadors (1533). He faced strong German and US competition for Old Masters being sold from Britain’s great aristocratic collections, driven by an agricultural slump.

Described as a fastidious bachelor, quiet and unostentatious, he is overshadowed by characters like the charismatic first director, Charles Eastlake. But Nicholas Penny, the former director of The National Gallery (2008-15), has written that Burton effectively “created the National Gallery as we know it today”.

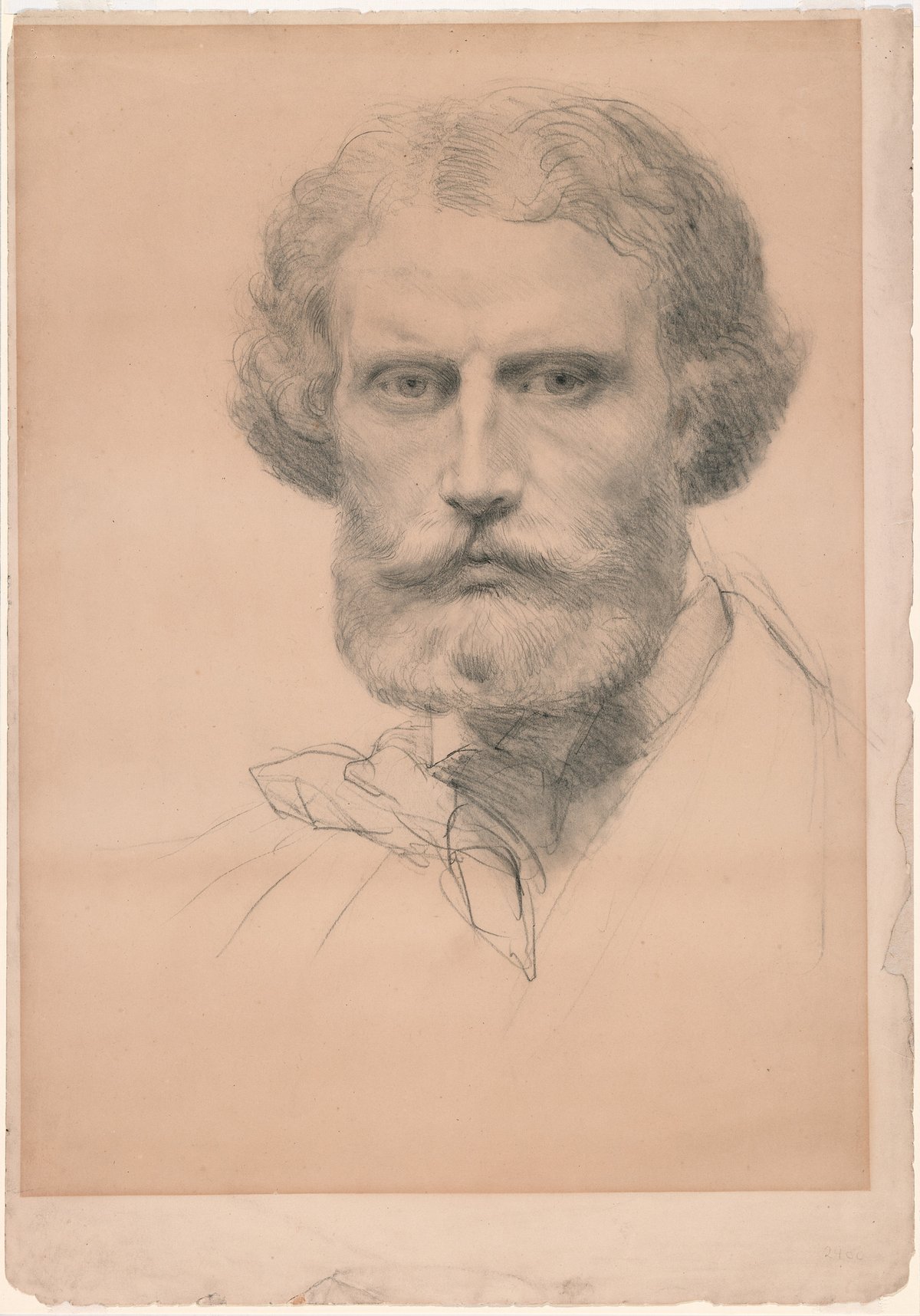

The exhibition For the Love of Art, which opens on 25 October (until 14 January 2018), focuses on Burton’s career as an artist with more than 70 works gathered through international loans. It includes his romantic painting The Meeting on the Turret Stairs, also known as Hellelil and Hildebrand (1864), voted Ireland’s favourite picture; his portraits of Mary Palliser, to whom he was betrothed for ten years; and the poet George Eliot. But a final room is mostly devoted to his directorship in London.

National Gallery of Ireland

“Burton has an awful lot of research on him that needs to be written up,” says Dr Marie Bourke, a curator at the National Gallery of Ireland. “I wanted to make the Irish public aware that although they just know him as an artist, he had this late chapter in his career, when he devoted himself 200% to the National Gallery in London.”

Penny describes how Burton gave up painting so completely as director that it is said he left an unfinished work on an easel. “He had an artist’s eye for things but he really was a scholar,” he says. “He always did very careful research on pictures and was interested, as scholars tend to be, not just in famous names but in other artists as well.”

Penny notes that when Burton stayed in the post until the age of 78, critics complained that he ran out of energy and lost works to the Berlin museums’ celebrated director Wilhelm von Bode. But earlier he energetically pursued works in Europe, improved framing and the decorative style of the National Gallery, and personally oversaw a new catalogue published in 1887. He organised and labelled works into schools rather than chronologically.

Vitally, Burton’s tenure saw the first subscription fund to tap the wealthy to buy major works for the gallery. The art historian Elena Greer writes in a catalogue essay: “Arguably, this moment was the origin of the notion—still relevant today—of foreign Old Master paintings being regarded as British national cultural heritage and the National Gallery as the rightful depository of such works. These early campaigns to ‘save’ Old Masters for the public collection precede the foundation of the National Art Collections Fund in 1903.”