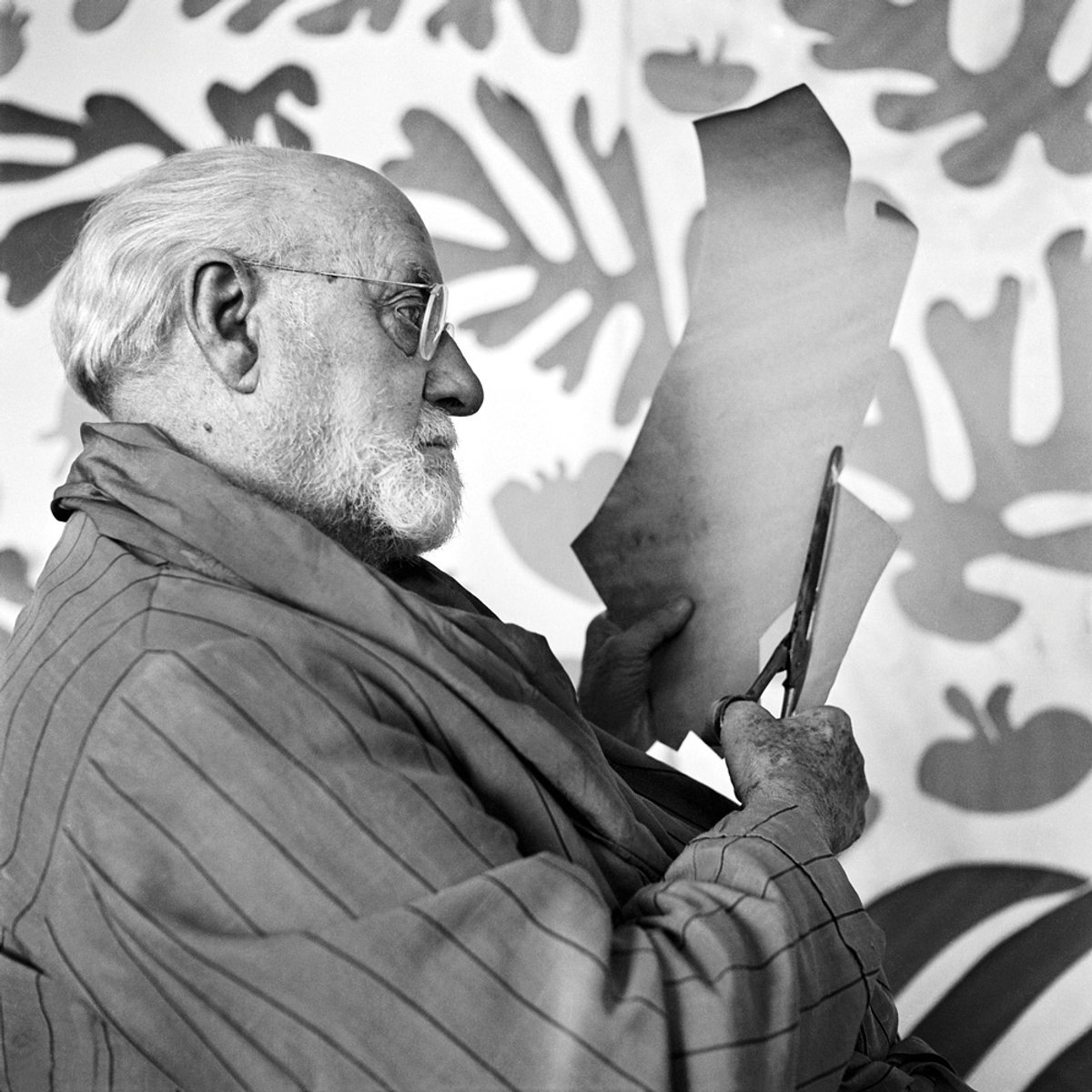

The court of appeal in Versailles is passing judgment this month on a long-running and complex civil case over two cut-outs by Henri Matisse, worth a combined $4.5m, that the artist’s heirs claim vanished—along with hundreds of other works—while in storage.

The story begins in 2008, when the heirs of Pierre Matisse, the artist’s younger son, a renowned art dealer in New York, claimed ownership of White Palm on Red and Green Snail on Blue before filing a criminal complaint for fraud and detention of stolen goods in Paris on 15 January 2009 against persons unknown. The works had been withdrawn by Sotheby’s from its Impressionist and Modern sale in New York on 7 May 2008, for which they had been estimated at $1.2m to $1.6m and $2.5m to $3.5m respectively.

The case, which has never before been reported by the media, involves companies based in Hong Kong and Panama, a Parisian dealer and Matisse’s heirs. The judgment, due in October, “will be considered a test for all works of dubious origin”, says Georges Matisse, Pierre’s grandson, who adds that the heirs are acting not only to recover works they believe are rightfully theirs, but also “out of respect for the artist, because many were never intended for commercial sale, and finally for the integrity of the art market”.

Cut-outs withdrawn from sale

On 7 March 2008, two months before the planned sale in New York, Sotheby’s presented the cut-outs to the Paris-based Matisse expert Wanda de Guebriant, who asked for more information on their provenance and the identity of the seller. When a representative of Sotheby’s hinted that the gouaches came from the collection of a well-known “marchand de couleurs”, Lefebvre-Foinet, an art supply company founded in the 1880s, she became suspicious; as far as she was aware, Pierre Matisse had never parted with them. De Guebriant concluded that she would not be able to provide a certificate until the chain of provenance was clarified.

On 28 March 2008, Sotheby’s received a letter from Georges Matisse, on behalf of the family, claiming ownership of the cut-outs. The auction house withdrew them from sale. A Hong Kong-based company named Rozven, acting on behalf of the seller, then fired back with a lawsuit against Georges Matisse. Rozven said that it had bought both cut-outs from Côté Art, a business run by the Paris-based dealer Jérôme Le Blay. The company was only registered in Hong Kong on 13 March 2008, as the works were being presented to De Guebriant. Rozven is owned by a Panama-based company named Vasuman. Nothing is known about the real owner, but Le Blay is designated as its sales agent. Responding to an order from the court, Rozven provided an invoice, also dated 13 March 2008, according to which it bought the two works for €200,000.

On 23 September 2010, the civil court in Nanterre, near Paris, dismissed Rozven’s case, stating that “by demanding to stay anonymous and by refusing to justify the provenance” of the lots, it was “solely responsible for the cancellation of Sotheby’s sale”. Rozven appealed, seeking €2m in damages from Georges Matisse. “The refusal of the certificate is incomprehensible, as no one denies the authenticity of the works,” stated its lawyers on 6 July in front of the court of appeal in Versailles.

Heiress of Lefebvre-Foinet

The Matisse family “simply wants to control the market”, says Le Blay, who adds that the cut-outs originated from Josette Lefebvre, the heiress of the dynasty owning the art-supply company that also provided shipping and storage. He tells The Art Newspaper that she gave or sold him several works, after he helped her with her archives when she retired near Paris. Le Blay produced a certificate showing Lefebvre’s signature and stating that they “came from the collection of her father, who owned them at least since the 1960s”. Wanda De Guebriant believes that this is impossible, several documents indicating that they were still in Pierre Matisse’s apartment in Nice in 1972. Only then did he put them in storage at Lefebvre-Foinet’s.

The Matisse family believes that the cut-outs vanished from the storage facility in Paris along with hundreds of drawings, engravings, gouaches and even sculptures. Their suspicions were first raised when a bas-relief by Matisse was offered for sale at a small auction house in France in 1990, less than a year after Pierre Matisse’s death. Consequently, Lefebvre gave back 11 sculptures to Matisse’s heirs. Several hundreds of other lost works were recovered from the children of Lefebvre and those of her companion, who was Lefebvre-Foignet’s shipping agent, Jean Robinot. Many others came from a local butcher, who helped Josette with gardening, and his wife, who became one of her close friends. According to an invoice that was found during the criminal investigation, the two cut-outs were bought by Le Blay from the butcher’s widow for €136,500 on 7 February 2008—a month before they were presented to De Guebriant. Saying that he acted in good faith, he points out that the criminal procedure was dismissed in 2014, after Josette’s death, the judge considering that he could not have been aware of her suspected misappropriation.