Canada today (27 September) inaugurated its first national Holocaust Monument, in Ottawa, an endeavour ten years in the making. A grassroots campaign to build the monument was launched in 2007 by a student at the University of Ottawa, Laura Grossman, and construction on the C$9m ($7.25m) project began last year. It was supported by the National Holocaust Monument Development Council, with matching funds from the Canadian Government. The concept of monument, landscape of loss, memory and survival, came from Toronto-based Lord Cultural Resources, and was chosen in 2014 from a shortlist that included proposals from the architects David Adjaye and Ron Arad.

The monument focuses on three stories, says Gail Dexter Lord, the co-president of Lord Cultural Resources: the state-sponsored genocide of the Holocaust; the fact that Canada, like many other countries, did not give asylum to those who were being persecuted; and the 40,000 Holocaust survivors who came to Canada after the Second World War, and the contributions they made to the country. The monument’s design and construction was a collaboration between the New York-based architect Daniel Libeskind, the Montreal-based landscape architect Claude Cormier, the Canadian photographer Edward Burtynsky and the University of Toronto professor Doris Bergman, an expert on the Holocaust.

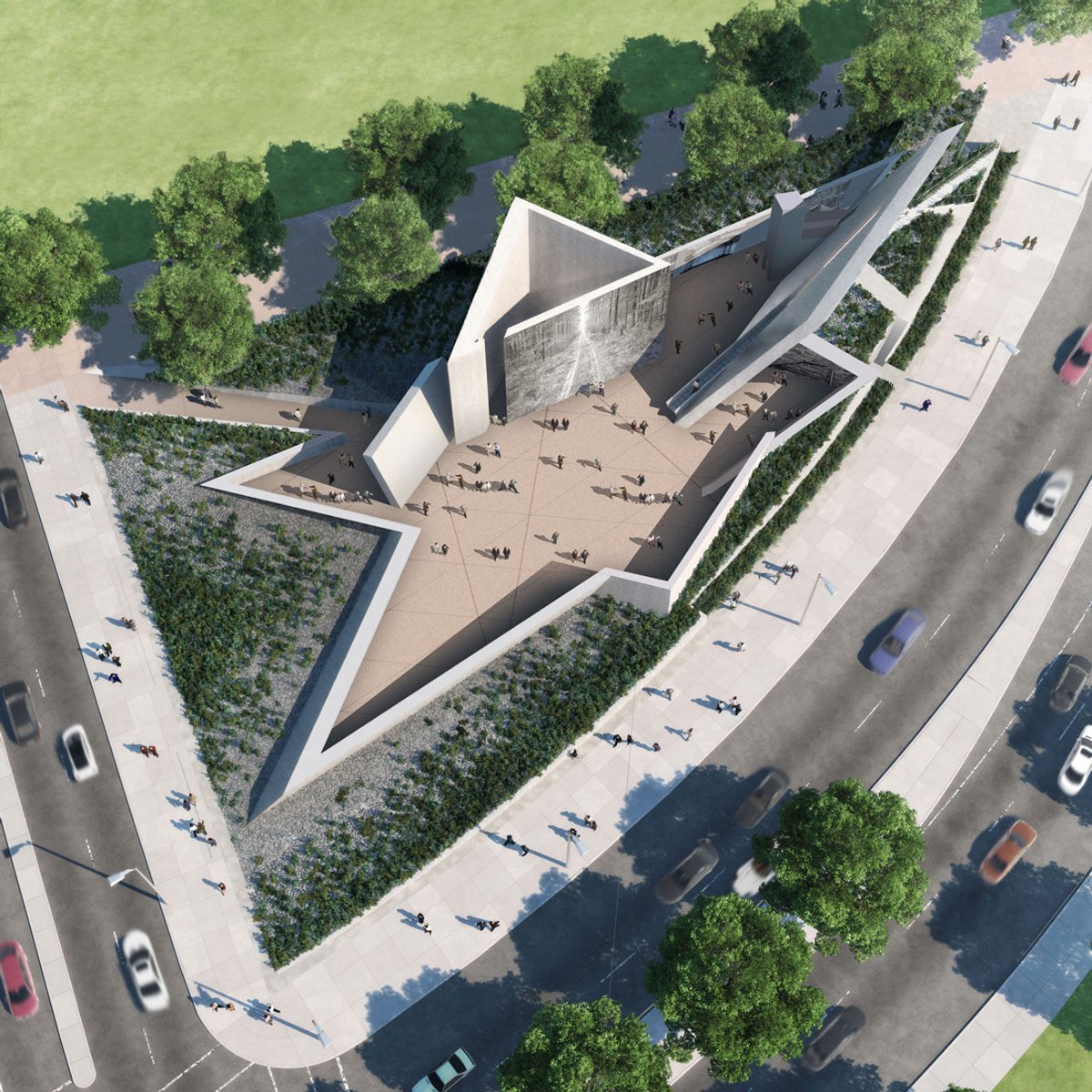

Visitors descend to enter and ascend to exit the 3,200 sq. m open-air monument, which is across from the Canadian War Museum, and can accommodate up to 1,000 visitors for public ceremonies. It is made of six concrete and metal walls, with plantings of conifer trees. From above, the monument is the shape of a skewed Star of David which, Lord says, recognises the Jewish victims of the Holocaust, but also other groups who were persecuted, such as homosexuals and Jehovah’s Witnesses. The monument includes photographs that Burtynsky took of Holocaust sites throughout Europe, including a field of grass and trees through which a railroad ran, taking more than a million people to their deaths. Forty-foot-high black-and-white reproductions of the images are embedded in the monument’s concrete walls.

“You can look at a landscape and just think it’s just beautiful, but in fact, some of the most terrible things that have ever happened to human beings happened there,” Lord says. The use of landscape imagery speaks to the importance of landscape in Canadian history and identity. The monument strikes a “balance between the universality of the Holocaust and our national reality”, Lord says, adding that these landscapes ask the visitor not only to contemplate the atrocities of the Holocaust, but also to think about the history of violence of the treatment of Indigenous people on Canadian land.