Is it too perverse to call Piet Mondrian the greatest US artist of the 20th century? True, he was born in 1872 in Amersfoort, the Netherlands, and spent youthful years in Dutch provinces like Domburg and Uden, where he developed a taste for Symbolism and Theosophy. His formative years were spent in Paris, which he first visited in 1911. He knew about Cubism second-hand by then, but direct exposure to Braque and Picasso deeply shook his style. Thereafter, in studios in Paris and the Hollandish town of Laren, Mondrian digested his Cubist lesson and reorganised his work. He broke down his landscapes, jettisoned his figures, refined his lines and muted his colours. In 1920, he made his real breakthrough in a Montparnasse studio, where he inaugurated the Classical Period for which he is best known.

Mondrian had a manifestly European pedigree, yet only in New York did he have his richest realisation: that to continue, his Classicism needed radical reinvention. In October 1940, aged 68, he stepped into Manhattan off the S.S. Samaria, where for four weeks he had been surrounded by 500 children sent abroad by their parents to escape escalating war in Europe. Whatever anxiety the experience introduced, his optimism did not abate. He was thrilled by New York—its pace and novelty, its admiration for abstraction, its typically American optimism—and felt it was the most perfect manifestation of the “New Life”, as he called modernity. “Enormous, enormous!” was his reaction upon first hearing boogie-woogie jazz, that St Louis invention, in the home of the painter Harry Holtzman. Lee Krasner later remembered Mondrian as a brilliant dancer.

New York afforded Mondrian an opportunity to fundamentally restructure his thinking. It was here, after settling into a Midtown Manhattan studio, that he began to reassess 17 of his European pictures, among them his best works, such as Trafalgar Square (begun 1939) and Place de la Concorde (begun 1938). These were clear, open, lively and neatly layered paintings, already successful according to his ideals at the time, yet Mondrian felt that they could not stand up to New York. They needed still more dynamism, an even less obvious sense of underlying stability and a crisper staccato pop. His solution was not excessive. With a few small, unbound bars of red, yellow and blue—finally freed from the constraints of black lines, allowed to float up to the surface of the picture plane—he broke open a new line of development.

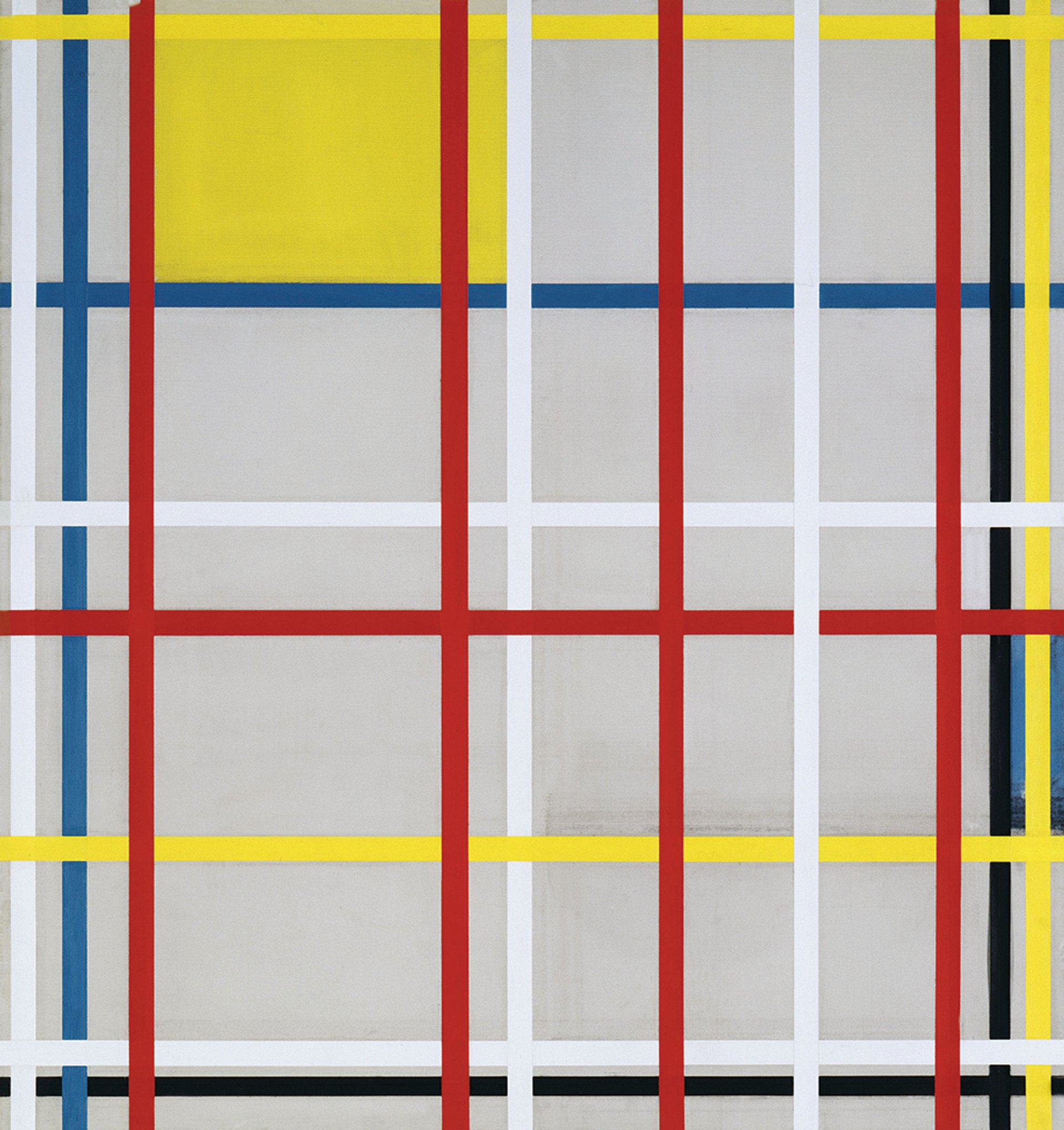

What remained was to reckon with the implications of his Transatlantic paintings, which Mondrian did with America always on his mind. By the end of his New York series, begun in 1941, the black line had completely disappeared, replaced by vivid, flashing bands of primary colours. Here was something altogether new, an attempt to lock in the Cubist grid through interwoven lines, a spatial grid so tightly bound that it is flush with the picture plane. In unfinished paintings like New York City 3 (1941), Mondrian came to see that for tradition to live in the New World, it needed a fresh imagination.

A distinctly Dutch show

The recent career survey of Mondrian’s work at the Gemeentemuseum in The Hague, titled The Discovery of Mondrian, had very few of his late pictures. Among the 300 works (all from the museum’s collection), the emphasis was on his early development, his time in Amsterdam, his engagement with Symbolism in the Dutch provinces and his discovery of Braque and Picasso in Paris. The show had a heavily biographical element, including letters from the artist to his sweethearts. The idea was to provide an alternative to the 1995 National Gallery of Art (NGA) survey in Washington, DC, which the current curators felt treated the artist too coldly and, more importantly, skirted the earlier works, which are in abundance in The Hague. Around 140 works were from before 1907, when Mondrian began engaging Modernism in earnest.

Mondrian/Holtzman Trust

In the 100th anniversary year of De Stijl, it was a distinctly Dutch show, a reclamation of Mondrian from Paris and New York and a celebration of his Netherlandish roots. Yet it seems a disservice to have only five of the Classical Period works (1920-32), none of the Transatlantic (1938-42) or New York pictures (1941-44) and to put the museum’s crown jewel, Victory Boogie Woogie (1942-44), Mondrian’s great unfinished work, in a room with period costumes. The desire to draw a full portrait of the artist and his life, including a sketch of the moment in which he lived, is admirable, but it flattens the quality of his work. Great paintings suffer when they are related to mediocre ephemera, and period items do not necessarily shed any light. There was too much in the show that is no good (including much of Mondrian’s work until 1907) and too little to prove his true achievements.

The real merits of this show will outlive it. Because the museum’s original impetus for the exhibition was to take stock of its Mondrian collection, conservation efforts have secured his paintings for future generations. New biographical research enriches our understanding of the painter and his relationships, which has strong potential to yield insight into his work. And it is worthwhile to periodically reassess Mondrian, whose work shines as brightly as it must have when he left it in his Midtown Manhattan studio upon his death in 1944.

Yet it seems a shame to mute the artist’s radicalism by focusing so heavily on his immature work at the expense of the late pictures, which have a distinctly American flavour. Against the NGA show and its emphasis on his mature work, it is too much of a corrective. It is true, as the curators argue, that Mondrian was open to reinvention long before New York. His jump in 1907 from a regionalist Dutch style into international Symbolism proves that he never hesitated to make bold gestures. His optimism, even in London in 1940 amid Nazi bombing, never failed him. But only in America did he discover a profoundly new dynamism without losing his signature style. The New York paintings speak to that revelation. They are the greatest fruits of his transatlantic lesson: that old ideas can be assimilated into new ways of life. And here we are—what it is to be American.

• The Discovery of Mondrian, Gemeentemuseum, The Hague, until 24 September

• Correction: An earlier version of this article misstated the date of an earlier Mondrian exhibition at the National Gallery. It was 1995, not 1994.