The US artist Robert Longo’s latest response to attacks on free speech includes a close-up of a café window riddled with bullet marks, which he based on a crime-scene photograph taken after a terrorist attack. He created Untitled (Copenhagen, February 14, 2015) in response to the fatal shooting in the Danish capital by an Islamic extremist who was targeting the Swedish cartoonist Lars Vilks and those who had gathered to hear him. The cartoonist, who has received death threats for his 2007 caricature of the Prophet Muhammad, escaped uninjured but a member of the audience was killed and the attacker went on to kill and wound others before he was shot.

Longo says: “I did a big drawing of the front [door] of Charlie Hedbo. I amped it up to make it look almost like an animal.” He calls the charcoal drawings, which can measure more than 2m high, “hyper-realist images, done on a scale partly inspired by Ab Ex works”.

The Copenhagen attack “was a Charlie Hebdo-inspired attempted assassination. Those motherfuckers are targeting artists not just political people,” Longo said. He was speaking ahead of the opening this week of Let the Frame of Things Disjoint, a solo show at Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac in London (15 September-11 November), which features a diverse range of subjects, many created recently and several drawn on a large scale. “It looks like an abstract painting with a little Jasper Johns thrown in,” he says, referring to the numbered bullet holes.

Longo’s drawing of a bullet hole in the door of Charlie Hebdo's office is another powerful, large-scale work, which went on show last year at Ropac’s Paris space. Longo said that the work proved therapeutic to a Charlie Hebdo cartoonist he met who survived the attack because he overslept and so was late for work. “He opened the door and found his friends. He sent me a sketchbook where he redrew my drawing from the black hole out and he talked about how my drawing had helped him, which was incredibly moving.”

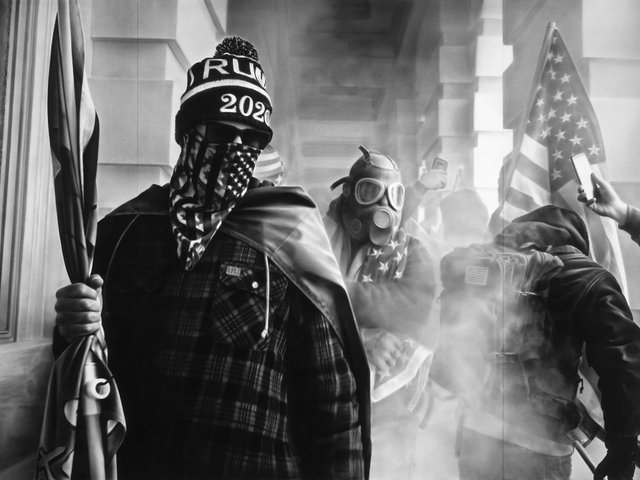

Politicised since high school, the Brooklyn-based artist’s latest works are even more so, depicting, for example, air strikes in Syria, a demonstration in California and a tattered US flag referencing Donald Trump’s presidential victory in Untitled (Election Day, 2016) (2017). “I grew up in the age of Reagan,’ he says. ‘He was like Trump before Trump. I hated Reagan and I always realised that a time could come when I could be told that, as an artist, ‘You can’t do what you want to do.’”

Longo has also created a small work that forms a calling card to London and references the history of the building that now houses Ropac’s gallery in Mayfair. This time the hatred was verbal. It reproduces the infamous calling card left by the Marquess of Queensberry when he burst into the Albemarle Club to confront Oscar Wilde about the writer’s relationship with his son. Untitled (Oscar Wilde note) (2017) features the words “Posing as somdomite [sic]”, written in anger by Queensberry. The insult ultimately led to Wilde’s disgrace and imprisonment after he lost a libel case against the aristocrat who gave his name to the rules of boxing, a coincidence that appeals to Longo.