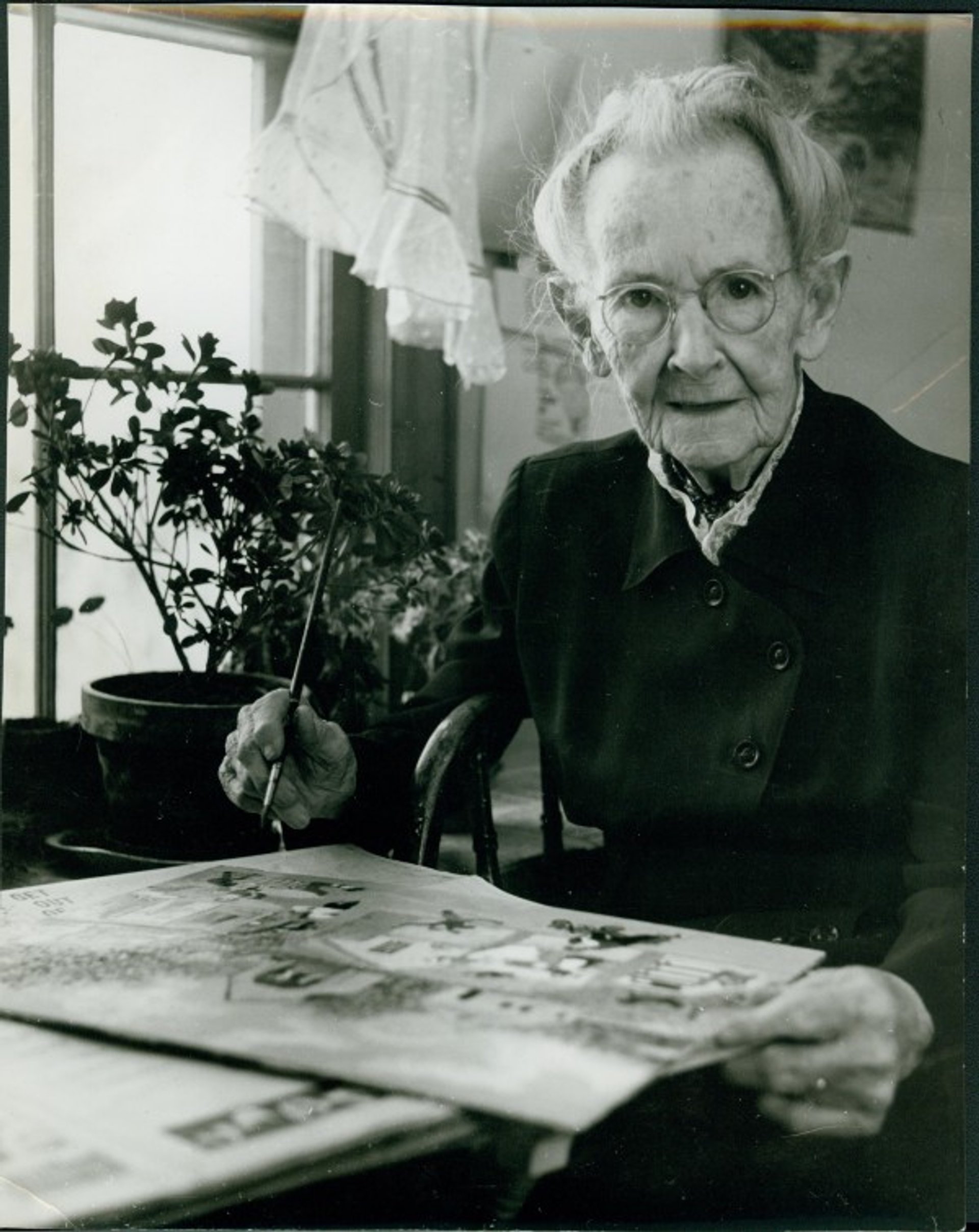

The Bennington Museum and the Shelburne Museum, both in Vermont, have produced a great show and catalogue covering the art of Anna Robertson Moses, who was born in 1860 on the eve of Lincoln’s election as president and died in 1961 at the dawn of the Space Age. We know her as Grandma Moses.

Moses was a farm wife in tiny Eagle Bridge on the New York-Vermont border when Otto Kallir, the Vienna refugee and dealer, discovered her in 1938. He introduced her to New York audiences along with his other artists, among them Klimt, Schiele and a raft of German Expressionists. Alfred Baur included her in a group show on originality in contemporary American art soon afterwards. She became the most famous Outsider artist in America and an icon of Yankee charm.

She became a Vermont artist in part because there is no “Upstate New York School”. New York wouldn’t know what to do with her. She is part of the American Regionalist movement. The only painters getting rich in the 1930s were the Regionalists such as Thomas Hart Benton and Grant Wood. Moses was the Vermont variant. Marsden Hartley moved to Maine at the same time and retooled his art and marketing. He became a painter of Maine.

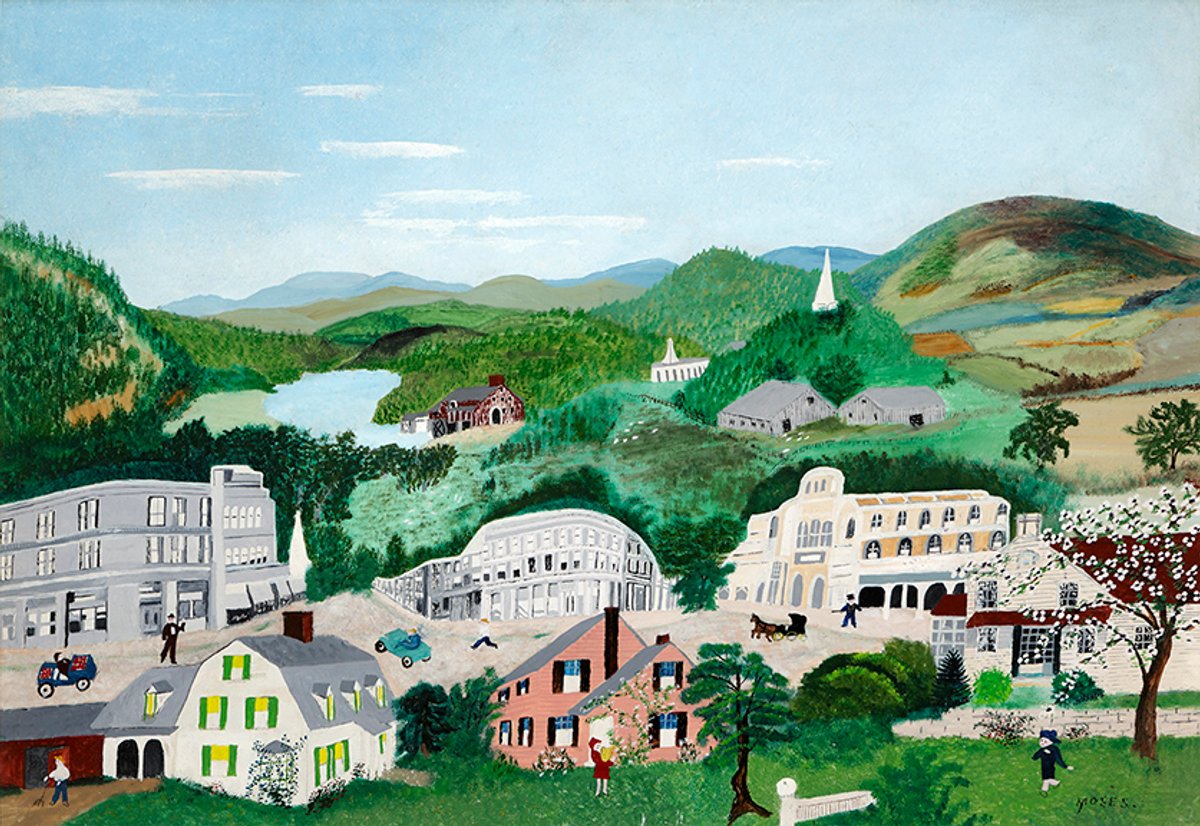

Collection of Bennington Museum

It’s no coincidence that Grandma Moses was discovered the same year Norman Rockwell moved from New York City to Arlington in Vermont, a few miles from her. He sought the austerity and authenticity of rural life. He stopped using professional models when he came to Arlington, preferring local farmers, factory workers, mailmen, country doctors and mechanics for their look of experience and character.

Robert Frost lived in Shaftsbury, the next Vermont town. His spartan verse on spartan subjects owes much to Vermont country life. Also in 1938, Our Town opened on Broadway. Arguably the best American play of its time, it is set in rural New Hampshire, though Grover’s Corners has many dozens of kindred communities in Vermont. It professes that we can see life’s truths most clearly in the simple, old, unsullied setting of the New England town.

Grandma Moses merged her art and her persona much as Whistler and Warhol did

Some of Moses’s modernity is coincidental. She had almost no training, and Outsider artists were becoming a vogue. Her paint surfaces have the feel of found objects in their yarny, rough texture. She came from a knitter’s world and a world where she made her own clothes and her children’s and then repurposed them—no sprezzatura here. Her space is weird, dream-like weird, the elements often stacked and unproportioned. Shadows have as much weight as objects.

She’s a realist on the subjects she chose: wedding days, snowfalls, town suppers, sugaring offs, summer picnics, woods bursting with spring. These are not fake. They’re punctuation points in a hard working farm life amid nature’s relentless demands. Her world wasn’t measured by clock time, which is city time, but nature’s time. In Moses’s world, nature made room for human rituals.

She was also a canny self-promoter. She merged her art and her persona much as Whistler and Warhol did. Academics might despise her because she got rich from the millions of Christmas cards, placemats and baby bibs illustrated with her work, but much of contemporary culture is about branding.

Mostly, academics live in cities and think people in the country are rednecks. In revisiting her, remember that Grandma Moses might have looked like the wife of Father Christmas, but in reality, she was more like Ma Joad.