Borders are being erected around culture. Newly empowered gatekeepers police the edges, issuing orders for the destruction of works of art if an artist crosses the line and causes offence; or is of the wrong ethnicity; or not close enough to a historical trauma to be permitted to comment on it.

The controversy over “cultural appropriation” has claimed its latest victim. Scaffold (2012) by the US sculptor Sam Durant, which was lauded when shown in the Netherlands, Scotland, and Germany, has been dismantled after protests erupted when it was displayed in the Walker Art Center’s new sculpture park in Minneapolis.

Scaffold is a powerful work about the death penalty: the steel and wood sculpture is a composite of the representations of seven gallows that were used in US state-sanctioned executions by hanging between 1859 and 2006. One recalls the largest mass execution in US history, when, in Mankato, Minnesota, in 1862, 38 Dakota Native American men were executed under orders from President Lincoln after the US-Dakota War; another, the gallows used to put to death four Lincoln Conspirators, in Washington D.C. in 1865, including the first woman to be executed by the federal government. One of the structures referenced in the piece is the scaffold used to hang Saddam Hussein.

When it was shown in Europe, Scaffold was praised by Amnesty International as a way of encouraging debate about capital punishment. It was crucial that the work was exhibited in the US, the only Western democracy to still have the death penalty. And 13 people so far this year have been executed in the US by lethal injection: six white men, six black men and one Latino man.

You might expect then that Scaffold would provoke anger about state executions. Instead, outrage exploded largely over the ethnicity of the artistTiffany Jenkins

You might expect then that Scaffold would provoke anger about state executions. Instead, outrage exploded largely over the ethnicity of the artist, for Sam Durant is white. The indigenous Dakota community took exception to the representation of the Mankato gallows in the sculpture. Indigenous activists protested that Durant was appropriating their history about which he had no right to comment and that the placement of the piece in a sculpture park trivialised the event.

After a meeting with the Dakota tribal elders, a decision was made to take down the sculpture and burn the wood in a ceremony, though they have since suspended this pending further consultation. Perhaps they realise that burning art is never a good look.

The case is one of many similar controversies. Earlier this year, New York’s Whitney Museum of American Art selected for its biennial Dana Schutz’s work Open Casket (2016), a painting of the body of Emmett Till, a 14-year-old African-American murdered in 1955 by two white men in Mississippi. The Berlin-based, British artist Hannah Black organised a petition to have the work removed and destroyed as she objected to a white painter responding to black suffering.

The Whitney defended its decision to show the work. But Durant and the Walker Art Center did not. As part of the agreement with the elders, Durant pledged to never recreate Scaffold and to transfer to the Dakota tribe his intellectual property rights to the work.

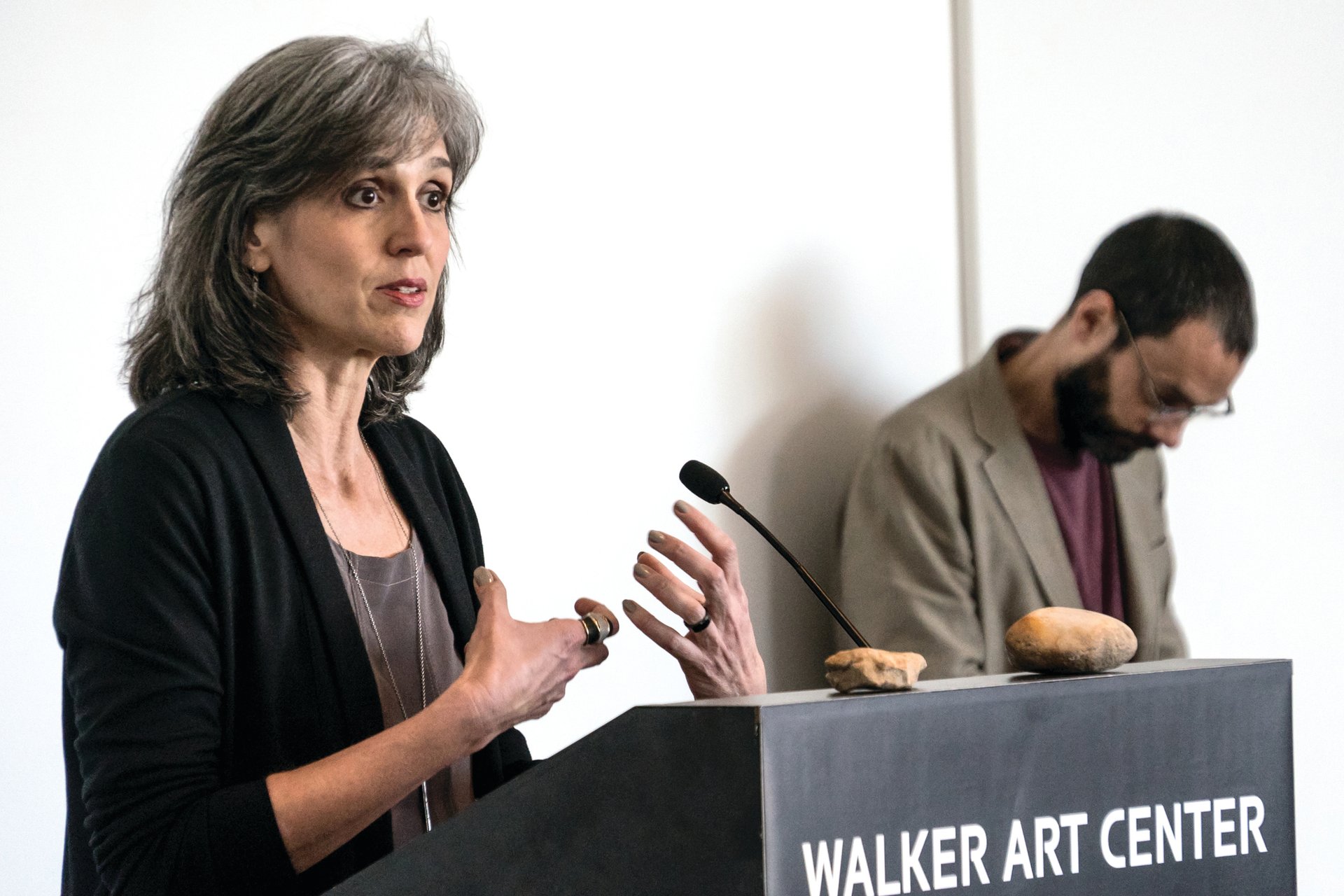

Olga Viso, the director of the Walker, issued an apologetic statement: “We are deeply, deeply sorry and pledge to be better stewards of our relationship with communities going forward.” Crumbling in this way will only encourage other demands for art to be erased.

What has happened is dangerous for art and politics. Fighting racism and injustice used to be about people coming together from different ethnicities to demand equality. It used to be about creating a colour-blind society and limiting state power.

To argue that an artist should not create a work because of their race will chill not only creativity but relationships between people; it rehabilitates the language of racial purity and suggests that unity and commonality is unattainable between people of different ethnicities.

Artists need to be free to explore all ideas and all history. They should be held to account for their work, certainly, but for its quality—not their identity. To argue otherwise is to limit an important empathetic act: thinking about another time and another place, and about how things could be different, is the basis for much of art. The future of which is under threat and could leave artists as silent as those who dangled from the noose.

• Tiffany Jenkins is a writer and critic, and the author of Keeping Their Marbles: How Treasures of the Past Ended Up in Museums and Why They Should Stay There, published by Oxford University Press