Vittorio Scarpati lay dying in Manhattan’s Cabrini Medical Center for five months before finally succumbing to Aids in 1989, one of the thousands of New Yorkers to fall victim to the epidemic that ravaged the city—and the wider world—in the 1980s and 1990s.

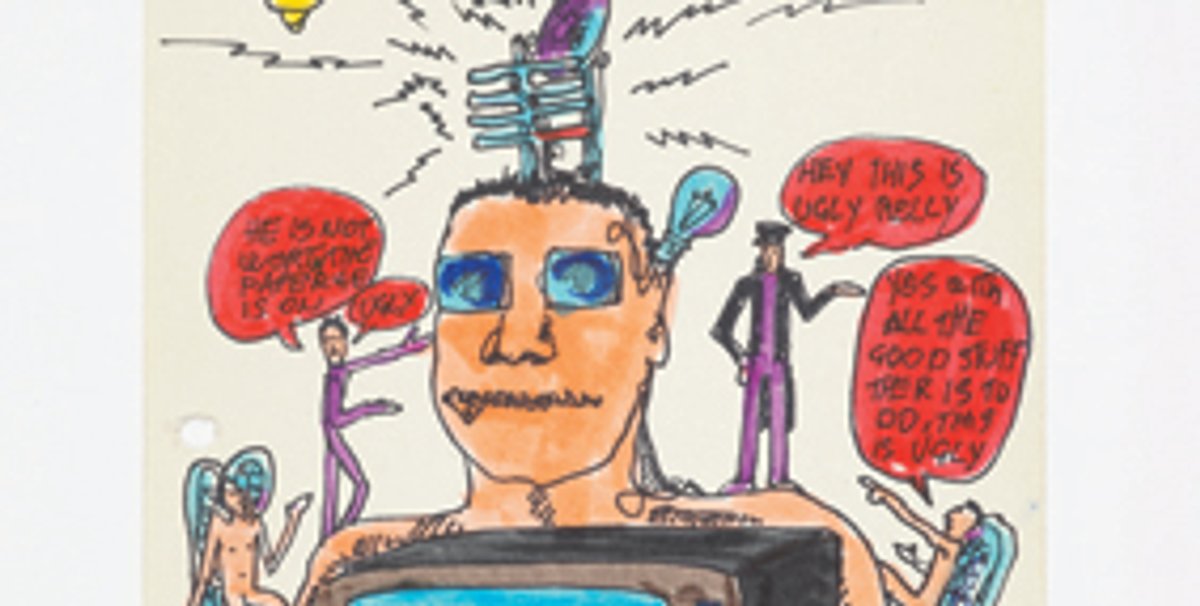

In those months, Scarpati, a 34-year-old cartoonist and artist from Italy, filled notebooks with hundreds of felt-tip pen drawings that illustrated his plight—the collapse of both lungs, the pneumonia, the gurgling suction machinery inserted into his chest. In one self-portrait, daggers pierce his torso as he collapses to his knees saying, in Italian, “That’s enough.” In another, he opens his shirt and golden light pours out. Skeletons appear often, as do broken hearts.

Scarpati “was gripped by a frenzy of pent-up art communication that exploded out of him”, wrote his wife, the writer and actress Cookie Mueller, who would die of the same disease a few months later. “Seen chronologically, this is a journey of extreme pain made bearable by his sublime imagination. It’s the story of a trip along the paths of Vittorio’s fantasies, and for a man who hasn’t felt the warmth of sunlight or the sweet breezes of fresh air for four months there’s a lot to create in the inward eye.”

Scarpati’s deathbed drawings appeared that year at New York’s 56 Bleecker gallery and as part of Witnesses: Against Our Vanishing, an exhibition of artists’ responses to the Aids epidemic, curated by the photographer Nan Goldin at Artists Space. The next year, Kyoto Shoin International published the drawings as a book, with a preface by Mueller, under the title Putti’s Pudding—a term Scarpati used to describe the “piles of angels” he liked to draw.

More than two decades have passed without the works appearing in public again. But this month, the non-profit gallery Studio Voltaire in London is opening an exhibition featuring 40 of Scarpati’s drawings from the hospital, as well as archival documentation and Mueller’s preface to the book (9 September-5 November). “The drawings contain everything about that situation from the perceived transcendent bliss of an angelic afterlife to the sheer horror of having your body pierced by all that technology,” says Paul Pieroni, the show’s curator. “I’m always interested in the potential radicality of the recently antiquated and building a narrative around this stuff.”

The exhibition will be an introduction to Mueller and Scarpati for many Londoners. Even Pieroni had not heard of Mueller until relatively recently, while reading a biography about the artist David Wojnarowicz in which she appeared as a minor character. “For some reason I was just attracted to her,” he says, echoing a sentiment often expressed by those who encountered the heavily eyelinered blonde during her heyday in New York. “She was the starlet of the Lower East Side,” Goldin once reminisced, “the queen of the whole downtown social scene.”

The cult film director John Waters, who cast Mueller in his movies Pink Flamingos, Desperate Living and Female Trouble, among others, has called her “a writer, a mother, an outlaw, an actress, a fashion designer, a go-go dancer, a witch doctor, an art-hag, and above all a goddess”.

When the novelist Chris Kraus saw Mueller read at the St Mark’s Church Poetry Project in New York toward the end of her life, she was “so moved and impressed” that she signed Mueller up as the first author for publisher Semiotexte’s Native Agents series. “I couldn’t believe she was still seeking a publisher, but apparently so—agents and editors had told her she’d have to do x, y or z with the manuscript for them to consider it. And she was already sick, and she couldn’t,” Kraus says. “I think I started the Native Agents series around a desire to publish her work. I didn’t know Cookie at all, but I approached her and said we’ll publish whatever manuscript you want to give us.” The resulting book was Walking Through Clear Water in a Pool Painted Black, a collection of semi-autobiographical short stories published just a few months after Mueller’s death at the age of 40.

Scarpati was then, and remains, far less known than his celebrated wife. “Vittorio was a quieter background figure, a perfect foil for Cookie,” recalls Bill Stelling, who ran 56 Bleecker, the gallery that first showed Scarpati’s drawings in 1989. “He was smart, funny and trenchant.”

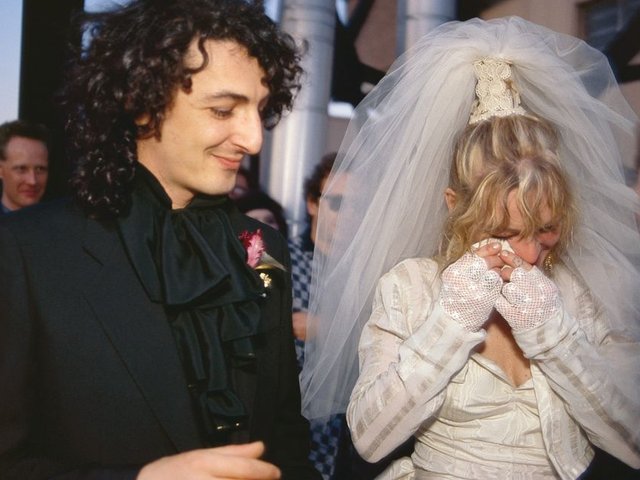

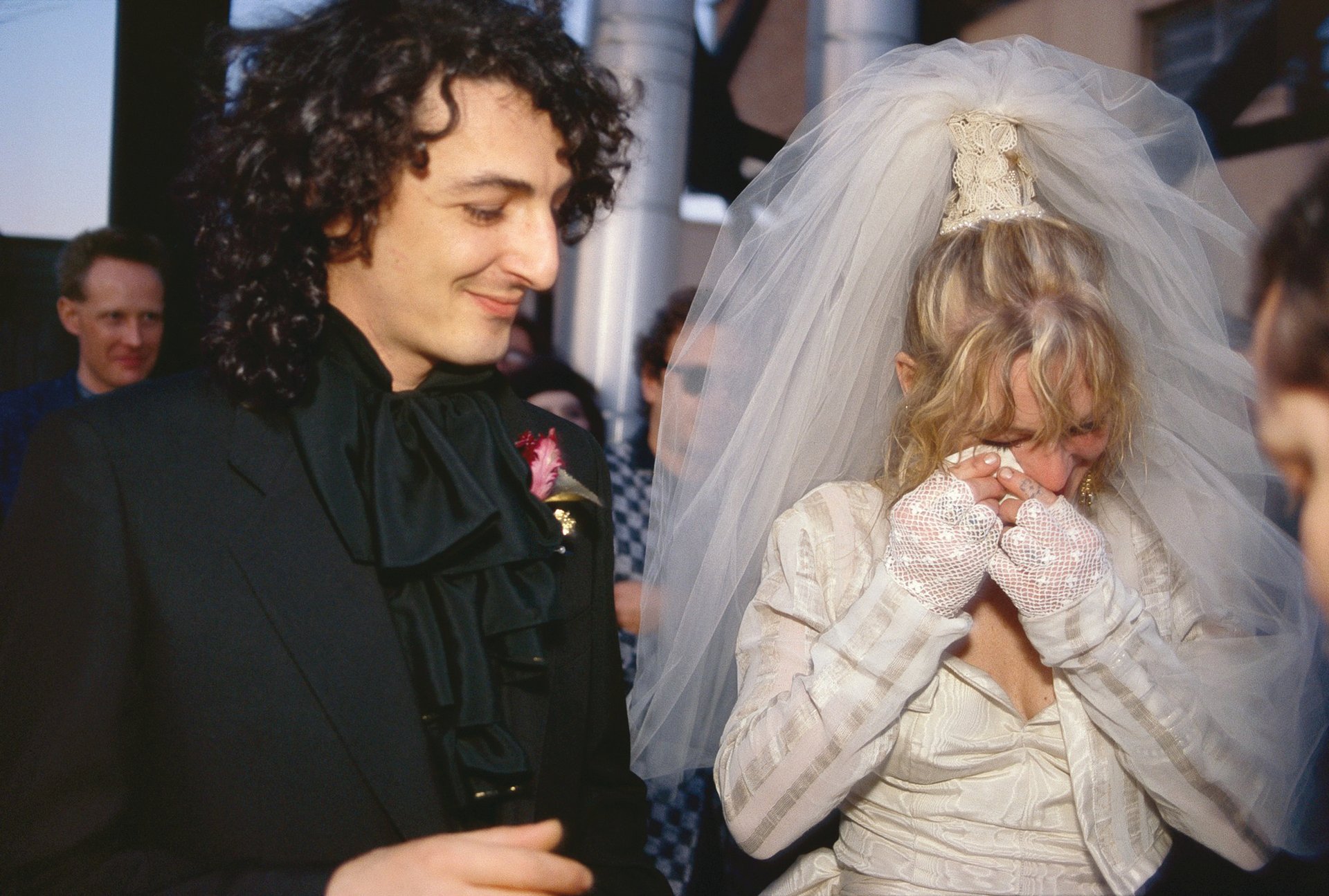

The couple met during the summer of 1983, in Positano, Italy, a coast town south of Naples so paradisal it looked like “Walt Disney made it”, Mueller wrote. She was immediately impressed with Scarpati’s cartoons and “his ease with pen and ink, brush and colour”, she wrote. “The images just flew out of him effortlessly.” Both Scarpati and Mueller were heroin users and knew they were HIV positive when they married three years later. But neither understood—indeed, no one did—what that really meant.

Goldin has said that she was with Mueller on Fire Island in New York when they first learned of Aids in 1981, referred to as a “gay cancer” at the time. “Cookie just started reading this item out loud from the New York Times about this new illness… we all kind of laughed it off. We certainly didn’t think of its magnitude. It didn’t affect us, like: this is going to be our future.”

Eight years later, Goldin photographed Mueller, by that time walking with a cane, beside her husband’s casket. Soon after, she shot Mueller in hers. Pieroni imagines that Mueller and Scarpati might have gone on to become major artists if only they had had more time. “That’s a recurrent tragic motif among artists in that era of the Aids crisis—never quite getting to be focused because they were all fucking dying.”

Nevertheless, the couple remain part of a distinguished art historical movement and, with Putti’s Pudding, contributed a crucial document to it. The book was a “visionary project about strength and beauty and pain”, Pieroni says. But more than a historical artefact, the drawings are also an intimate look into the mind of an artist we might not have otherwise known. With cartoonish images of dolphins, nurses, birds and a sumo wrestler, Scarpati revealed his humour as much as he did his anguish. On Valentine’s Day he drew a skunk holding a heart out to another skunk, writing beneath: “Happy Valentine to my beloved. I can’t believe me drawing hearts!!”

Pieroni suggests: “They’re very pure and very playful and kind of full of sweetness.” Stelling says that the drawings “reflected the daily horrors he experienced, but with irony and humour. When you look at the drawings, there are some that will make you smile.” The New York-based writer Linda Yablonsky, who was friends with both artists until their deaths, adds: “I thought they were amazing at the time and still do, extremely pointed as well as poignant. What stands out is an acknowledgement of his condition and treatment, as well as his will to live, both in reality and through his art—the best path he could take.”

Pieroni is sensitive to the criticism that this historical demographic—the artists who both flourished and perished during the Aids epidemic in New York City—has received so much attention that it runs the risk of becoming romanticised. “There was a danger that there was a weird fetishisation of this era and illness,” he says. But he received the support of Mueller’s son, Max Wolfe Mueller, who loaned many of the drawings for the Studio Voltaire show, and in the end decided to go ahead with the exhibition. It is an important reminder of how lucky we are to live in a time where an Aids diagnosis is no longer a death sentence, he says.

“Sometimes I wake up and I don’t know why people make art, why there are all these artists and institutions and magazines,” Pieroni says. “It feels sort of self-regulating, like it’s just regulating the pointlessness. But if someone’s on life support and they’re still making drawings, well, that feels to me like a justification for the whole thing.”

Like her husband, Mueller worked until the very end of her life. In one of her final pieces for a now defunct magazine East Village Eye, in which she penned a satirical health column called Ask Dr Mueller, she wrote an elegy for her generation: “Fortunately I am not the first person to tell you that you will never die. You simply lose your body. You will be the same except you won’t have to worry about rent or mortgages or fashionable clothes. You will be released from sexual obsessions. You will not have drug addictions. You will not need alcohol. You will not have to worry about cellulite or cigarettes or cancer or Aids or venereal disease. You will be free.”

© Nan Goldin, Courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery

Goldin’s ballad of life and death

Nan Goldin first pictured Mueller and Scarpati together in Cookie and Vittorio’s Wedding (1986), one of the photographs in her seminal slideshow and artist book The Ballad of Sexual Dependency, capturing Goldin’s milieux in New York, Provincetown, Boston, Mexico and Berlin. Goldin assembled the Cookie Portfolio after Mueller’s death in 1989. It contained 15 photographs, including devastating images of Scarpati and then Mueller in their caskets. “I used to think that I couldn’t lose anyone or anything if I photographed them enough,” Goldin wrote in an accompanying text. “I put together this series of pictures of Cookie from over the 13 years I knew her in order to keep her with me. In fact it shows me how much I’ve lost.” —Ben Luke